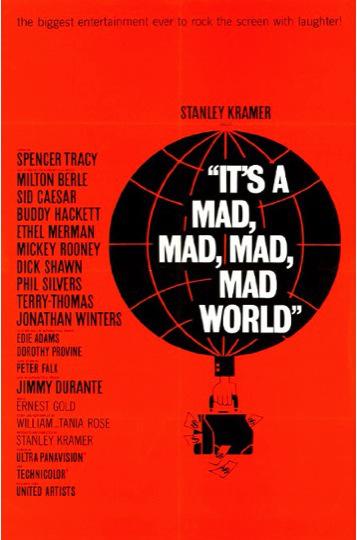

Film Poster

It was a golden idea. Take as many major stars as a film budget would allow and set them on a madcap search of buried treasure. It was a perfect American comic premise built around two essential tropes: the American open road as symbol for the pursuit of happiness and the unassailable and American belief that we are all destined to strike it rich. It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (196), directed by Stanley Kramer and starring every single major star of film and television in the 1950s–everyone of them–is an American classic and an essential film for anyone interested in saying such things.

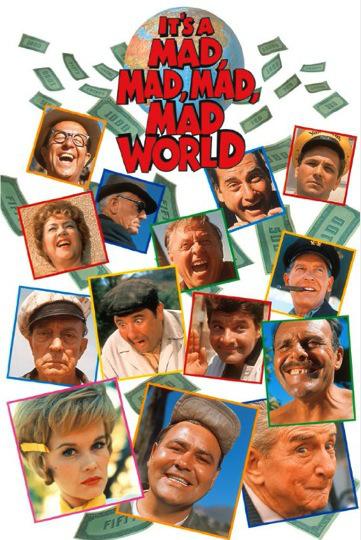

Trying to Share–Madness ensues

“Every man, including the old bag [Ethel Merman] for himself!”

The title uses “mad” four times, for those who are uncertain just how mad the film is. Kramer, it seems, had wanted to use it five times but was convinced to hold the number to four because five would be redundant. To clarify: five is redundant; four is OK. There are lots of people in Hollywood who are paid to make such decisions, so we should trust them. Kramer later regretted giving in to the pressure to choose four. This fact may help explain why an early draft of his later film starring Spencer Tracy and Sydney Poitier had the title, “Guess Which Five People Are Coming to Dinner.” But I am getting off topic. I am happy with four, so let’s just leave it at that.

The film was an immediate hit and earned critical accolades as well, a difficult task for film comedies historically. It became one of the highest grossing films of 1963. It was nominated for Golden Globe awards for best musical/comedy film and for Jonathan Winters for best actor in a musical/comedy. It won an academy award for sound editing. AFI lists it at #40 for its list of the best American film comedies.

The American Dream–just beneath the surface

The film’s strength is its combination of our cultural confidence in the road as symbol for self-development and discovery and the contradictory mainstream belief that we are, in the end, a community of freedom loving individuals on a shared pursuit of happiness. We are a democracy. In this context, the film takes on a more satirical potential with the simple plot structure that takes this open-road ideal from its most romantic notion and reduce it to its most cut-throat race to find buried treasure; Americans of the mainstream as crazed road-pirates. Lennie Pike, the common-man character played brilliantly by Jonathan Winters, provides the best piece of dialog revealing this core satirical voice within the film: “Then they all decide that I’m supposed to get a smaller share! That I’m somebody extra special stupid, or something! That they don’t even care if it’s a democracy! And in a democracy, it don’t matter how stupid you are, you still get an equal share!”

Sounds like class warfare to Bill O’Reilly. Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad.

Democracy

The Criterion Collection released the film on 21 January 2014, and, as with all Criterion productions, the breadth and depth of material provided in support of the film may encourage further analysis of the film and renewed interest. That is a good thing. The Criterion It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World offers the complete film as Kramer had hoped to release before accepting cuts required by United Artists. This director’s cut runs 197 minutes (the theatrical version was cut to a more modest, though still long, 154 minutes). That seems worthy of a fifth “mad” in the title.

It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad, World was released in November 7, 1963, a few weeks before the mainstream ethos of the 1950s would end abruptly with the assassination of President Kennedy. The jarring slingshot of the national sensibility into the impending trauma of the 1960s has stifled the film for subsequent generations, despite its initial success in the box office and the high quality of the comedic performances. Its silliness and playfulness, for many viewers, has trapped it in the amber of the mainstream open-road ideal of normalcy. The characters, in the end, seem simply perverse caricatures of middle America. The defining sensibility is then simply silliness. The road as mainstream outlet for affirming adventures of the post-war dream withstood subversion of Kerouac and the Merry Pranksters but could not survive in tact the murder of the President of the United States as he traveled the open road in Dallas, in an open car. Madcap road adventures had come face-to-face with sheer madness.

a balancing act

But it is time to take another look at Kramer’s Mad-x4 World. It has a place in American humor classrooms and overall American film comedy canon beyond its whimsy, though its playfulness is enough for my tastes to keep in in moderate rotation. It is a zany road-trip adventure filled with slapstick humor and broad physical comedy and playful dialog. It is also, with its long list of comedic performers in main roles and in cameos, a survey of American film comedy. As such, it can be viewed as a primer on mainstream American comedy of the first half of the twentieth century. It is a madcap film (fourth use of “madcap”), but it may also have more in common with other subversive satires of the 1960s than has been readily assumed. Perhaps the Criterion edition will encourage a more comprehensive look at a masterwork of American humor. Mad, mad, mad, mad, mad. Five.