A depressingly long time ago, as a fresh faced young undergraduate at the University of Nottingham, I signed up to a module devoted to art in Nazi Germany, which was taught by Dr Fintan Cullen. Fintan and I never really got along all that well (this is a massive understatement – we absolutely loathed each other) but he was, I have to admit, a really impressive and rather floridly verbose teacher who really came into his element when dealing with the robust imagery and political ramifications of Nazi era art.

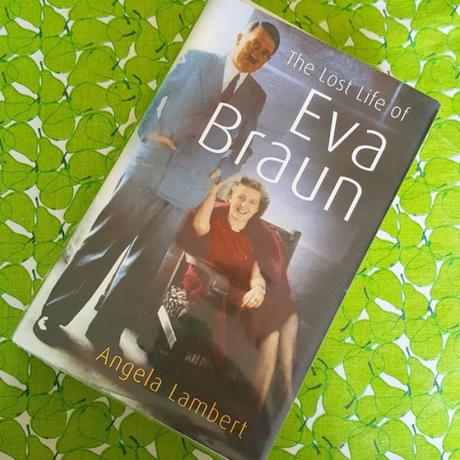

At the time, WWII had ended just fifty years earlier and it was still highly unusual for a course of this nature to be offered on a university syllabus. It was a very strange experience to be honest, not least because Nazi art is actually pretty terrible – bloody awful in fact. The course didn’t just look at all those ghastly paintings of strident young soldiers and shiny cheeked haus-fraus though, we also looked at the Nazi contempt for ‘degenerate’ art, their predilection for looting (the high ranking members of the party, most notably the repulsively avaricious Göring, had a habit of treated art galleries and museums like free shopping malls, an upmarket IKEA, if you like) and Hitler’s sophisticated use of imagery and art as propaganda. It was certainly a very eye opening experience and one that sprang to mind, even though I haven’t really thought about it for years, when I was reading Angela Lambert’s The Lost Life of Eva Braun

I was just twenty years old, not that much older than Eva Braun when she first met and fell under the spell of Adolf Hitler, when I found myself sitting in a darkened seminar room, watching the flickering images of Leni Riefenstahl’s chilling, awe inspiring and rather terrifying Triumph of the Will being projected on to a large screen at the back of the room. The often hilariously awful paintings of potent Aryan manhood had left me completely cold and I remember wondering what on earth the appeal was to the countless young women of my own age who had given themselves up so wholeheartedly to the Nazi cause and especially those who threw themselves so ardently at the Führer, who looked like such a squatly unprepossessing and rather absurd little man. What did they all see in him? I felt like I understood it though as I watched rows upon rows of fervent, smiling young German men and women mobbing their Führer as he drove past and then that rousing finale scene of the crowd rapturously singing Horst Wessel Lied together as a giant Swastika fills the screen and young soldiers march off to their bloody destiny.

Lambert’s book about Eva Braun is a biography with a difference as it occasionally interweaves the life of the author’s mother, who was born in Germany in the same year as Braun and so, during her early years at least, could be assumed to have shared much the same experiences as the elusive Eva, with that of her subject. Several reviewers have objected to this, seeing it as a pointless shoehorning in of her family, but I really liked it as I thought it added some more much needed context to Eva’s ‘lost’ life – lost in the sense that it was effectively obliterated long before she threw it away to accompany her love to his death. Although it seems like we now know pretty much everything that there is to be known about Hitler, his wife is a much more shadowy figure about whom we know very little, mainly thanks to Hitler’s own insistence that her existence should be kept a total secret from the German people – a bit like a boy band girlfriend, I suppose, so that he could be regarded as free, single and in desperate need of proper loving and maybe some home cooking too in the eyes of his millions of adoring female fans, who hung on his every word and sent him multitudes of embarrassingly torrid love letters on scented paper.

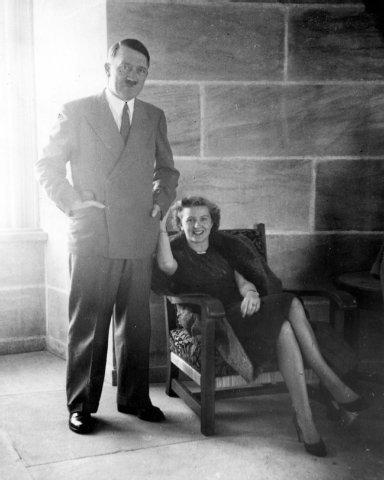

There are traces to be found of Eva Braun though, for those who are interested enough to look for them and I really enjoyed Lambert’s accounts of the research process, almost like detective work, that she tackled while writing her book as she visited archives to read Braun’s own journal (which came to an abrupt end before the second of her three suicide attempts) and pore over her photo albums. Eva was working in a photographer’s studio in Munich when she first met Hitler and she remained keenly interested in photography for the rest of her life, enjoying top of the range and hard to come by cameras and becoming increasingly skilled as the years went by although the necessarily cloistered nature of her existence, hidden away in the mountains, meant that her subject matter is rather repetitive – dogs, mountains, high ranking Nazis and their families and, above all, herself and the man that she had given up her life to love.

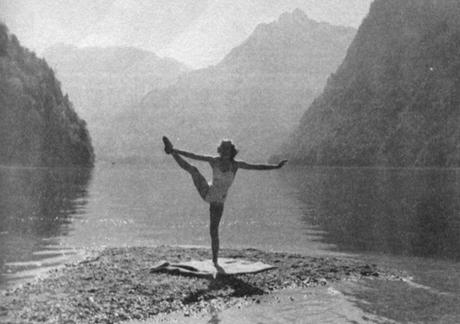

Lambert paints a picture of Eva Braun as a woman who is not exactly admirable but certainly very likeable and not nearly as stupid as she is often depicted. She took absolutely no interest in politics or current affairs and indeed was kept very much in the dark by her lover who regarded her as the blonde and buxom epitome of wholesome German womanhood and didn’t want to have her tainted by the horrible realities of his life. Perhaps typically, the only known instance of Eva ever taking an interest in politics was when she personally and successfully intervened against Hitler’s plans to ban the usage of cosmetics by women. Her interests, which revolved around fashion, film stars, gymnastics and photography, may well come across as rather shallow but I saw her as something of a Marie Antoinette figure – pampered, petted and indulged in her gilded cage and kept hopelessly and intentionally in the dark about the more serious matters that would eventually cause her own downfall. Like Marie Antoinette, Eva would also stand by her man and face her death with considerable and unshrinking courage but during her time as Hitler’s mistress at his mountain retreat of the Berghof, where she spent long, empty hours doing gymnastics, swimming, walking dogs, changing her clothes several times a day and taking snapshots, her dark and squalid end in the bunker beneath Berlin would have seemed completely inconceivable as she wholeheartedly and completely believed that her lover would win the war and was fond of telling people that he had promised her that when he did so, he would make Hollywood make a film about her life with her playing the starring role. Poor Eva.

However, tedious though her life undoubtedly was, she was living in unimaginable luxury compared to the vast majority of German women during the war. While Eva wore exquisite couture dresses, smelt of expensive French perfumes and dined lavishly and extravagantly at the Führer’s table, other women were doing without even the barest necessities of life, enduring bombing raids and starving as food blockades took their toll. For women from the Jewish, Roma and other communities, life was even worse and when one talks about Eva Braun, one has to ask ‘Did she know?’ Lambert talks at great length about Eva’s probable level of culpability or at least awareness of the Nazi atrocities that were being carried out under the orders of the seemingly genial men that she was hobnobbing with and taking snapshots of at the Berghof and comes to the conclusion that Eva almost certainly knew virtually nothing about what was actually going on and was in fact probably kept intentionally in the dark. She refers to interviews with other women in their circle, such as Speer’s wife Margarete, who denied knowing anything about the atrocities but then again, she would say that, wouldn’t she? Easier by far to pretend ignorance than admit that yes, actually you did know but did nothing but then again what could she have done?

Lambert recounts an anecdote about one of Hitler’s nieces confronting him at the Bergaus about the appalling treatment of a Jewish woman she had witnessed in Amsterdam, clearly believing that he must be in ignorance of such outrages and then dumbfounded when he reacted with defensive anger, which made it clear that he both knew about and condoned them. Eva was probably present when this happened but we don’t know what she thought of it, if indeed she thought anything at all. Certainly it is clear that it was frowned upon to bring up such subjects at the Berghof (the niece was never invited back again) so it perhaps isn’t surprising if the female inhabitants remained in blissful ignorance of the horrors being committed by their menfolk.

Lambert spends a lot of time answering the question ‘What did Eva Braun know?’ but never seems to address the perhaps more pertinent one asking ‘Would it have made any difference to her if she had?’ and while I can totally accept that Eva knew next to nothing about the Holocaust, camps and massacres, I’m afraid that I can’t believe that she would have walked out on Hitler in disgust if she found out what was really going on. She never joined the Nazi party and never showed any signs of believing their twisted ideology but her love for Hitler was the entire and total focus of her limited life – it was like she didn’t exist when he wasn’t around and her entire life was spent waiting for him to either visit or write or call her, like a doll in a cupboard, waiting to be brought out and played with when its owner is in town. Although she may well have been disgusted by the truth, she would, I am sure, have found a way of turning it around in her head to make Hitler the innocent victim in some way, perhaps manipulated by the likes of Himmler and Goebbels or perhaps even simply shrugged it off and pretended that it wasn’t true. Either way, as evidenced by the fact that she chose to take her own life with him rather than leave Berlin as she was urged to do (and remember that she had been kept so secret that very few people would have recognised her had she decided to leave), Eva would have stayed beside him until the bitter end no matter what.

Ultimately I found this a fascinating book, obviously bleak in places, especially when the author reminds us of the true horrors that were going on apparently without Eva’s knowledge or when the action turns to the miserable events in Hitler’s bunker at the end of the war when the Führer and his entourage were cornered like rats in a hole, cowering as the Russian and Allied armies advanced upon them bringing righteous wrath in their wake. Throughout the book I kept being troubled by thoughts that Eva resembled me and my grandmother but then realised that I wasn’t responding to an actual resemblance but to Eva’s sheer ordinariness, to the fact that there was nothing outwardly (or inwardly either really) outstanding or extraordinary about her. She was completely mundane. She could have been anyone.

It’s not a pleasant read but an intriguing and ultimately haunting one nonetheless and one that I very definitely recommend to anyone else interested in the lost life of this most shadowy and enigmatic of famous women.

******

I don’t have adverts or anything like that on my blog and rely on book sales to keep it all going and help pay for the cool stuff that I feature on here so I’d like to say THANK YOU SO MUCH to everyone who buys even just one copy because you are helping keeping this blog alive and supporting a starving author while I churn out more books about posh doom and woe in the past! Thanks!

As the youngest daughter of the Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, Marie Antoinette was born into a world of almost unbelievable privilege and power. As wife of Louis XVI of France she was first feted and adored and then universally hated as tales of her dissipated lifestyle and extravagance pulled the already discredited monarchy into a maelstrom of revolution, disaster and tragedy. Marie Antoinette: An Intimate History is now available from Amazon US and Amazon UK

Set against the infamous Jack the Ripper murders of autumn 1888 and based on the author’s own family history, From Whitechapel is a dark and sumptuous tale of bittersweet love, friendship, loss and redemption and is available NOW from Amazon UK

‘Frothy, light hearted, gorgeous. The perfect summer read.’ Minette, my young adult novel of 17th century posh doom and intrigue is available from Amazon UK

Follow me on Instagram.