The Lorax was my favorite Dr. Seuss book when I was little and now that I am an adult I even have an interactive version on my Android tablet. Although I am personally excited about The Lorax movie, I am not surprised that it has irritated some conservatives in America. Fox Business Network Host, and champion of the Once-ler, Lou Dobbs recently lashed out at The Lorax, arguing that the movie is an attempt to indoctrinate American children into liberal thinking by President Obama’s Hollywood supporters, who are using the movie to promote green technology and to criticize the top 1%. Perhaps Dobbs is correct about the intentions of Hollywood, I don’t know, but just how controversial are the ethical messages within the Lorax? The underlying theme of the story is environmental conservation, an American principle that began as early as the 17th century with a tradition and legacy that my own family helped to start.

Who is The Lorax? “He was shortish. And oldish. And Brownish. And mossy. And he spoke with a voice that was sharpish and bossy.” The Lorax speaks for the fuzzy tufted pastel pink, orange, and yellow Truffula Trees, the Swomee-Swans, the Humming-Fish, and the Brown Bar-ba-loots who eat Truffula Fruits. Eventually the Once-ler discovers the Truffula forest, and upon feeling their softer than silk tufts, tufts which smell of sweet butterfly milk by the way, he realizes that these trees are what he has been searching for all his life. He concocts an entrepreneurial scheme to harvest the Truffula tufts for the production of Thneeds, as furry multi-purpose sweater-like product. His venture takes off and the Once-ler invites his large extended family to join the booming Thneeds business. Continuous growth leads to innovations in the capital infrastructure, with the introduction of productivity enhancing industrial plant and equipment such as the Super-Axe-Hackler. The Truffula Trees can now be cut five at a time.

The Lorax continuously complains to the Once-ler that they should not continue cutting down Truffula Trees, but the Once-ler is never swayed, persisting in a fundamental disagreement that cutting down the trees is a problem since Thneeds are so useful and desirable for consumers. Even after The Lorax has to send the Brown Bar-ba-loots away for lack of Truffula Fruits to eat, even after the air pollution from processing massive quantities of Thneeds forces the Swomee-Swans to fly away, and even after the Gluppity-Glupp from the Once-ler factories saturates the pond where the Humming-Fish swim, the Once-ler will not put a stop to the production of Thneeds. The Once-ler ignores the warnings of The Lorax until all of the trees and inhabitants of the Truffula Forest are gone, and the whole environment has become a waste land. The Once-ler is telling this story to a young boy throughout the book, and at the end the Once-ler gives the last Truffula Seed to the boy with instructions to replenish and safeguard a new forest so that hopefully The Lorax and his friends would come back to live.

The book has been around since 1971, apparently indoctrinating children into liberal environmentalist thinking without their free consent through the tyranny of parental story time, but never before has the medium of computer animation been used to truly hypnotize the children with this tale. I jest of course. I still love The Lorax, and I believe it has a good message for kids, but I also recognize that costs, tradeoffs, and economic issues exist with environmental policies, and this is the concern that inspired Dobbs’ rant. Later this month I am going to post an essay that I wrote a few years ago about wind farms in my home state of Washington, and it is interesting to note that after I completed this analysis I was not convinced that the benefits of pursuing wind power outweighed the costs. Therefore, I don’t believe I was ever indoctrinated into liberalism while reading The Lorax over and over again when I was little. Nevertheless, I also think that the sentiment of environmental conservation and sustainability is an appropriate ethical lesson for children to learn. When this lesson is communicated via a theatrical release of an animated feature the parents of America have a free market choice about whether to take their children to see The Lorax. Lou Dobbs should not worry so much.

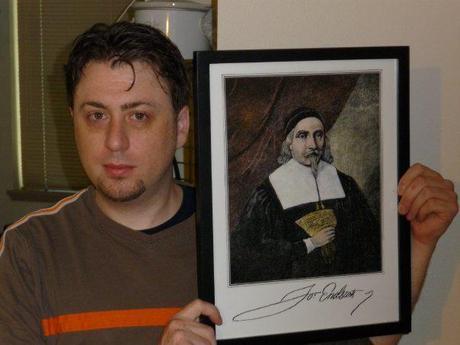

My ancestor, Captain John Endecott, arrived in the New World on September 6th 1628 aboard the ship the Abigail, and he assumed the Governorship of the recently formed Massachusetts Bay Company. Along with the remnants of a previous settlement at Naumkeag, Endecott founded the town of Salem in order to prepare the region for Puritan colonization. This was eight years after the Pilgrims had arrived at Plymouth and two years before the new Governor John Winthrop would move the capital of Massachusetts to Boston. John Endecott has a rich and interesting history, but much of it tends to be overshadowed by the Pilgrims and Winthrop, as well as Endecott’s own most infamous moments, such as an incident with flag desecration, starting the Pequot Indian War, and the persecution of Quakers. Besides these there are other fascinating facets of John Endicott’s life and leadership which have bearing on the political controversy at hand. The relevant historical gems for my purposes here are Endecott’s role in the establishment of earliest conservation laws in America and the Endecott Pear Tree.

After Winthrop became Governor of Massachusetts in 1630, Endecott remained the leader of Salem town. He was officially elected to a board of seven selectmen in a governing council in 1638, but the minutes for the council meetings were in his handwriting since the beginning of town when he was Governor. There is every reason to believe that he was heavily involved in town governance decisions the entire time. The Colony governed by allowing the freemen of the individual towns to decide amongst themselves in regards to electing officers and constables, as well as the particular laws and schemes for land usage and grants. The official policy in Salem around 1634 was that families of the smallest size would receive grants of 10 acres, but this amount land could increase with larger families (Mayo 134-137). It did not take long before land usage problems developed.

In January of 1636 the selectmen of Salem became concerned that the good timber, which sat on the lands surrounding the town, the lands that had not yet been granted to individuals yet, was being overharvested and exported to other markets by residents. Endecott and the other selectmen called a town meeting and they passed an export tax on of five shillings per hundred feet on all timber exports. It was John Endecott who recorded the vote according to biographer Lawrence Shaw Mayo, suggesting that Endecott was the chief sponsor of the vote.

Unfortunately, the export duty did not solve the problem and in 1640 Endecott wrote a letter to Governor Winthrop asking him to have the General Court pass a general conservation law for the Colony. General conservations laws would turn out to be years away, but in the winter of 1640 many of the esteemed townsmen planned a venture in shipbuilding, and in their desire to support this business opportunity the resident’s of Salem became more focused on the need to conserve timber. Endecott called anther town meeting and a new law was passed which confiscated all of the good downed timber within two miles of the town. In May of 1641 the town passed another law which established a fine of 20 shilling for every felled tree that did not reside on one’s own private property. According to Mayo, the Salem conservations laws passed under the leadership of John Endecott were the first to be concerned with protecting natural resources in America (Mayo 138-139).

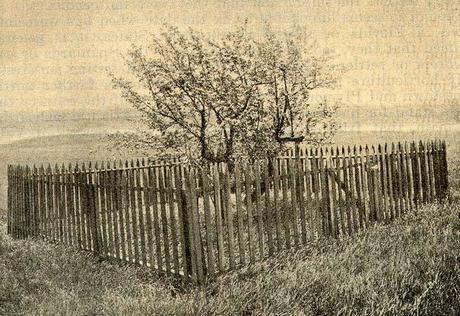

Besides his role in the earliest conservation laws in America, John Endecott also planted the oldest living cultivated fruit tree in North America. The Endicott Pear Tree was planted sometime between 1632 and 1649, and the tree still stands today. The Reverend William Bentley wrote in 1806 that, “This week Capt. Endicott brought me some pears from the Old Endicott Tree, which tradition and public opinion assigns 176 years of age. It stood without sensible injury in the violent storm of October, 1804, when some of its younger neighbors fell victims to the fury of the wind. It continues to yield many bushels and I am every year supplied from it to gratify my friends who are fond of feasting on the fruit of the first settlers and of the first Governour.” (Mayo 75) In 1810 the Reverend Bentley brought some twigs from the tree to former President John Adams at his home in Quincy, and Adams is reported to have responded weeks later with, “I have grafted a number of Stocks which have taken very well according to their present appearances and have distributed others to several Gentlemen in this and the Neighboring Towns. Mr. Norton of Weymouth, who loves Endicott Divinity full as well as you and I do loves his Memory and history too as one of our Fathers - descended from one of the most Ancient Families in New England and Old England he cannot be indifferent to the Name of Endicott, through no doubt he will say, Vi ea nostra voes.” (Mayo 75)

The Endicott Pear Tree was memorialized in 1890 by the American poet Lucy Larcom, in an ode she penned for the observation of Arbor Day, an early precursor to the modern Earth Day. After considering the legacy of John Endecott’s role in the earliest American conservation laws, and given that his planting of the oldest living cultivated fruit tree in North America was celebrated by environmentalist movements going back one hundred or more years, I find that Governor Endecott and The Lorax have much in common. Just as The Lorax spoke for the Truffula Trees because they could not speak for themselves, John Endecott spoke for Salem’s trees in early colonial America. Just as the Lorax teaches us about the necessity of conservation, the Endecott Pear Tree teaches us about sustainability and preservation. Tragically, on July 27th, 1964 vandals hack-sawed off all of the Endecott Pear Tree’s branches. While the tree has recovered from damage, a clone of the Endecott Pear Tree has been grown and stored at the National Clonal Germplasm Repository in Corvallis, Oregon so that its legacy might be preserved (Postman). I believe that the related tales of the Lorax and the Endecott are appropriate lessons for young Americans, and don’t constitute liberal indoctrination as such. These ideas are deeply rooted in our traditions as Americans.

Photo of Endecott Pear Tree taken in May 1920.

Jared Roy Endicott

The Governor’s Tree

Lucy Larcom

Let us take a trip, in rhyme,

To the old Colonial time.In his shallop, from the Bay,

Came the Governor one day,

Up the slow tide of the creek,

On its inland shores to seek-

May be - just an hour of rest

From the homesick groups that pressed

Round him everywhere he went,

In the new-born settlement.Governors, we are aware,

Though they shirk no public care,

Through they hold the people dear,

Do not always want them near;

Sometimes they must draw apart

From the crowd, to read its heart.

Landing on a green slope’s side

Gazing round the region wide,

Over wind-swept forests free,

Down the inlet to the sea,

Quoth the Governor, “What harm,

If I here lay out my farm,

Plant my orchards, so my maize,

And in peace live out my days?

In my little sloop sail down,

When I must, to Salem town,

Ruling the good folks well

As if I should with them dwell.”Grave old Governor Endicott

Always did the thing he thought-

Finished what he had begun-

Did it, if it could be done

So this deed he planned was wrought;

Birchwood for his farm he bought;

Where the yeoman felled his wood-

Site whereon his mansion stood-

Shaded spring whereof he drank,

On the pleasant willow-bank;

By these tokens you may trace

Endicott’s abiding place.Up and down his grape-vine walk,

Pacing silent, or in talk

With retainer, friend, or guest

Or, perchance, with boyish zest,

Tasting some new-flavored fruit

That within his grounds had root,-

Fancy paints the Governor

Who is best remembered for

Something all can do, who please:

His delight was - planting trees.Trees he planted, trees he sold,

Not for silver not for gold,

But for soil to set them in;

Two trees would an acre win.

Orchard Farm grew large, and why?

Taxes were not over high;

When an apple tree or so

Bought a homestead, call them low.Orchards up and down the shore

Grew where birches sprang before.

From the Governor’s thrifty thought

Men a good example caught.

Wenham, Boxford, Beverly,

Bloom with orchards since that day.Winthrop, with his men, came down

Now and then from Boston town

(Turnpikes had not yet been made:

Streams to ford, and bogs to wade);

Footsore, tired, and wet, no doubt;

What the two Chiefs talked about,

Sitting at their council fire,

Does not at this hour transpire.

Looking forth, they must have seen

Dancing waters, slopes of green,

Golden cornfields, trees on trees,

Beautiful in sun and breeze.In the desert, paradise

Making glad their pilgrim eyes,

Laying down awhile their cares,

The two Governors - ate pears -

Porbably; we may suppose

That they did, since no one knows;

And our Governor did take pride

In his pear trees, side by side

With his sun-dial on the lawn,

Measuring out a golden dawn

For the sturdy colony

Whose leal citizens we are.

Doubtless they foretasted there

Wondrous growths the land should bear,

When, transplanted to this soil,

Nursed by faith, and fed by toil,

Freedom’s grafts on this new shore,

Should bring forth good fruits once more.Who would not be proud to say

Of the dead he does to-day,

If it be a worthy shoot

From an honorable root,

That, when centuries have passed,

Bloom and fruitage still would last, -

Still a growing, breathing thing-

Autumn, with the heart of spring.Such a wonder you may see;

For the patriarchal tree

Blossoms still, - the living thought

Of good Governor Endicott.

Fruit again this year to bear;

Honor to that brave old pear!What our fathers did, we know;

Set out trees, and made them grow;

And their best bequests we find

In the growths they left behind;-

Trees of honor, faith and truth,

Vigorous with undying youth,

Blooming on and breathing, still,

Freshness that no frost can chill.Over seas the pear tree came

Endicott has left to fame.

No need, now, so far to go,

Better trees beside us grow.

Here’s an oak that sprang before

Our beloved poet’s door,

On the very knoll he named,

By memory to be famed.In his neighbor’s hearts, as long

As the land resounds his song,

Planted by our Governor’s hand,

Like the pear tree may it stand

While the centuries come and go.

And the children’s children say,

“This’s the Brackett Oak you see,

Is it not the fine old tree?”Wait we yet our land to see,

The true home of Liberty;

When the rich and poor shall share

Gold and silver, - free as air;Dwarfing vice and blighting want

Nevermore a fireside haunt;

Hearts and minds together move,

One in knowledge and one in love,-

Nor one life be left to grope,

Cheated of its human hope.Freedom’s morning will have come,-

Dawn of the Millennium!

Sheltering and sheltered are men,

Knit together, body, soul,

In a nation sound and whole.Has the scorn yet been sown

Whence so grand an oak is grown?When a Governor plants that tree,

May we all be there to see.

Subscribe in a reader

Subscribe in a reader

Works Cited

Larcom, Lucy. “The Governor’s Tree.” Historical Collections of the Danvers Historical Society Volumes 5-6. Danvers Historical Society, Google Books. 5 Aug. 2012. Web. 3 Mar. 2012

Mayo, L. S.. John Endecott: A Biography. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1936. Print.

Pinchefski, Carol. “Lou Dobbs Bashes ‘Arrietty’ and ‘The Lorax’ as a Liberal Conspiracy.” Forbes. 23 Feb. 2012. Web. 2 Mar. 2012

Postman, Joseph D.. The Endicott Pear Tree: Oldest Living Fruit Tree in North America. 5 Aug. 2002. Web. 3 Mar. 2012

Dr. Seuss. The Lorax. New York: Random House, 1971. Print.