I live in a house of sci-fi fiends. As I write this, everyone else – yes even the cats – is glued to Agents of Shield. The tropical fish have stopped swimming in circles and now stare out towards the blue glow of the television. Their little mouths open and close in shock at the revelation that the good guy is in fact the bad guy. (At least this week. That could all change by next week.)

I live in a house of sci-fi fiends. As I write this, everyone else – yes even the cats – is glued to Agents of Shield. The tropical fish have stopped swimming in circles and now stare out towards the blue glow of the television. Their little mouths open and close in shock at the revelation that the good guy is in fact the bad guy. (At least this week. That could all change by next week.)So here I sit, huddled in the room off the living room, writing a realist novel with a touch of humor.

This, it seems, is the lot of the realist writer. My sixteen-year-old daughter writes sci-fi fan fiction and posts her stories online. They get 1000 views a day. She spends hours on Photoshop making Gifs of clips she has taken from Agent of Shield videos or Dr Who. Then she posts the Gifs on Tumblr and she gets dozens of new followers a day.

I'm not remotely jealous of my daughter – I am thrilled that her writing gets so much attention. I haven't read all her science fiction stories, but I have read the fantasy novel she's working on, and I've read pieces of fiction and reflective essays she's written for English at school. She can write, and I am proud of her.

However, I would love to have hundreds of people waiting patiently for the next installment of anything I write. Okay, yes, when I wrote about the time I was attacked as a teen, there were a few people eagerly awaiting the next instalments - and they knew I'd survived! But not thousands, or even hundreds.

At its best, realist fiction is that thing nobody is supposed to say they write: literary fiction. Only other people can decide that your writing is literary; it’s conceited to say so yourself, apparently. People have said my first novel is, so that’s okay. My second – well, we’ll see. At the moment, it’s a romantic comedy, at least in my mind.

At its worst, realism is depressing, and possibly self-indulgent. Actually even at its best, it can be depressing. I’m thinking about James Kelman’s novel How Late It Was, How Late, which won the Booker way back in nineteen-somethingty-something.

So it can be depressing. But it doesn't have to be. It can be tricky, intellectual stuff, which only somebody with a PhD from Princeton understands. (No, that’s not a dig at Joyce Carol Oates, though I was disappointed by Mudwoman, her most recent novel.) But it doesn’t have to be that either. James Kelman’s Booker win was slated more often because of its apparent lack of intellectual rigour and its use of the F-word. (Rumour has it it’s used 4000 times.)

Almost all my favorite authors write realism. Some of them write quirky fiction that takes you into minds that are out of the ordinary. Some realist writers take you into utterly ordinary minds but somehow manage to make them seem extraordinary. Some, like Anne Tyler or the late Carol Shields, do both. The key thing about literary fiction is it it takes you into people's minds. You don’t just rollick along chasing after bad guys (or bad aliens.) You might chase after bad guys, but you'll be taken on an interior journey too so you feel what the hero/ine is feeling as he or she chases.

More often though, there aren’t bad guys, and the major conflict is inside the characters rather than between them. The two books I mentioned above are examples of that: in How Late It Was, How Late, the main character is a Scottish drunk who has been blinded in a beating by police. The book is a stream of consciousness by this man, an unreliable narrator who is also paranoid. Although his girlfriend has disappeared and he gets into struggles with bureaucracy, it’s clear that his main enemy is himself. In Mudwoman, Joyce Carol Oates also has an unreliable narrator whose mental health is far from sound.

Some critics say realist fiction lacks imagination. Taking those two books again, it’s probably true that Oates knows enough about Ivy League universities to get her setting without over-extending her imagination. But James Kelman has never been a drunken Glaswegian conman. And Mudwoman also includes scenes from the main character’s disturbing childhood, including when she’s buried in mud. In most recent Anne Tyler novel I’ve read, The Beginner’s Goodbye, the narrator is a man. Tyler isn’t – so I’d guess she used her imagination. I certainly have in every piece of fiction I’ve written and I have only one piece that isn’t realism.

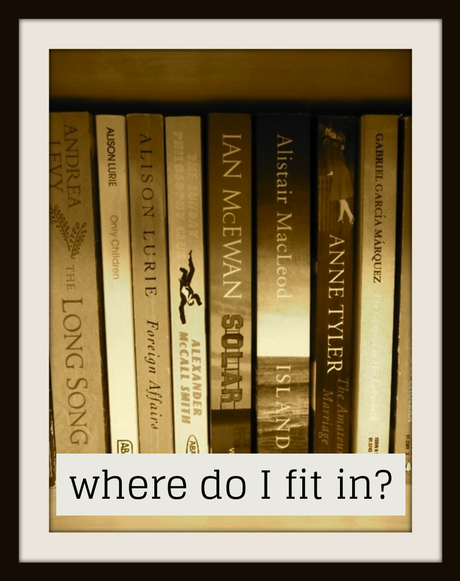

Some critics say realist fiction lacks imagination. Taking those two books again, it’s probably true that Oates knows enough about Ivy League universities to get her setting without over-extending her imagination. But James Kelman has never been a drunken Glaswegian conman. And Mudwoman also includes scenes from the main character’s disturbing childhood, including when she’s buried in mud. In most recent Anne Tyler novel I’ve read, The Beginner’s Goodbye, the narrator is a man. Tyler isn’t – so I’d guess she used her imagination. I certainly have in every piece of fiction I’ve written and I have only one piece that isn’t realism.You might have noticed that in book stores and libraries there’s no such category as realism. Sometimes you might find “contemporary fiction,” but just as often after you’ve browsed through science fiction, crime, romance and historical fiction, you’ll come to the shelves marked “general.”

This has made things just a little bit tricky when it comes to connecting with other authors writing in my genre - because we don't have one! It also makes reaching out to new readers who might be interested in my books more challenging than it might be if I wrote in a defined genre. I struggled to know where to place my novel in Amazon’s categories. Would “literary fiction” put people off? Would “women’s fiction” deter men from reading? And would “women’s fiction” seem to cosy? (Come to think of it, why is it that writing by women gets marginalised and not considered suitable for half the population?)

The answer to my dilemma about how to categorise my fiction has come from an unexpected source. Since the beginning of April, I’ve been taking a Social Media Bootcamp course, run by Julie Deneen of Fabulous Blogging. The course is aimed at bloggers, not novelists, but hey, I’m both. One of the first tasks Julie set was create Pinterest boards based on our blog topics. Another lesson was on hashtags. Both these exercises got me thinking in more depth about what defines my blogs. I realised that the word that best captures what both this site and my Inquiring Parent blog are about is “mindfulness.”

Then I also realised that it also fits my fiction perfectly. Of course, there’s no such genre as Mindful Fiction in your local branch of Barnes and Noble or Waterstones. But when people ask me what type of novel mine is, that’s what I’ll be saying from now on. I think it might just catch on.