A ship in harbor is safe, but that is not what ships are built for.

- William Shedd

Continued from Act 1:

The 14th Antarctica Marathon (Saturday, March 30)

Race morning arrived in the usual manner, with Andrew’s comforting voice reminding us over the Vavilov‘s PA that it was time to run a marathon on the coldest, highest, driest, darkest and windiest continent on Earth. Hooray! Fortunately the day promised to be optimal (in the Antarctica sense of the word), with temperatures hovering around a balmy -5°C (23°F). More importantly though, wind speed was a near-negligible 12 knots (14 mph), assuaging my concerns that I’d be stumbling 13.1 miles through an unforgiving headwind (and the other 13.1 with a brisk tailwind).

I inventoried my gear one last time. All race-day nutrients – energy bars, gels, etc. – had to be removed from their original packaging and all paper wrappers left on the ship, in accordance with the 1991 Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty. This wasn’t a problem, since for convenience sake I always liquify my race-day nutrition in my water bottle. Per Thom’s instructions I’d prepared two such bottles, which I planned to leave at the start/finish area.

In a dining hall alive with the clatter of breakfast dishes and the buzz of pre-race jitters, I waited as long as possible to eat my usual stomach-sanctioned meal of granola and peanut butter, which I’d brought with me from California. Several steps stood between us and the starting gun – the donning of the tomato-red Wet Skins that would keep us warm and dry, the loading of the zodiacs, the short ride to King George Island, the process of funneling everyone from zodiac to start line – and with 4+ hours of running ahead of me, I wanted to maximize the nutritional payback of my carefully choreographed breakfast.

The first zodiacs launched at 7:15am, with 12 passengers per zodiac. After a short 5-minute ride under gray skies and across smooth water, we beached near Bellingshausen Station and stepped ashore for the first time in 3½ days. Two Gentoo penguins splished and splashed in the water nearby. Stepping out of my Wet Suit, I could still feel the ground swaying underfoot as I tried to coax out my land legs. Moreover, the residual effects of the Transderm patch that I’d removed 36 hours earlier continued to wreak havoc on my short-range vision. Discomforting as my still-dilated pupils were, I was confident they wouldn’t upset my ability to run in a straight line for several hours.

How does a warm-weather Californian train for a marathon in Antarctica? Much as I hate to divulge trade secrets, here it is: I bought stuff. More specifically, windproof stuff. Compared to my typical all-season California running attire, I felt like the Stay-Puft Marshmallow Man in my three upper-body layers (REI wool base layer, synthetic Under Armour mid-layer, Columbia wind- and waterproof outer jacket) and two lower-body layers (REI fleece-lined tights, Pearl Izumi lightweight running pants), plus balaclava that I was hoping to shed early in the race.

Talk about happy feet… Rich’s own have carried him through over 300 marathons

Katie – who as a spectator would be doubling as a volunteer – was even more polar-ready, given that she’d be standing around for an indeterminate amount of time. She wisely wore her Wet Suit and rubber boots at all times, together with her Arctic Parka from The North Face that was so down-filled and poofy, I entertained the thought of hanging bricks from her sleeves so she wouldn’t blow away.

As Thom announced two minutes to start, the One Ocean crew hurriedly set up plastic buckets lined with green trash bags to serve as makeshift latrines. Fortunately I’d been able to attend to my most pressing needs on the ship, and after a lightning-quick stop at the latrine I jogged to the start line. For many of the bundled-up runners gathered beneath it, the unassuming white canvas banner represented the culmination of a lifetime of marathon-inspired blood, sweat and tears (with more to come). For others of us, this would be continent #2. And for two runners, this would be their first marathon on any continent.

This is how I envision an Antarctica Walmart on Black Friday (footage courtesy of Anita Allen of Marathon Tours):

Regardless of what road you’d taken to get there, Thom’s starting-gun cry of “GO!” triggered a collective release of whole-body tension, as the slow-moving stampede of runners – including members of the Russian and Uruguayan bases – followed the leaders along the dirt and up the initial ascent. And almost immediately, I dismissed all thoughts of a sub-4:00 finish. The first mile (which, given the course layout, we would be running six times) was an absolute mess. This was trail running at its damnedest. The deep, hardened ruts carved by the Bellingshausen ATVs, combined with the sporadic patches of ice, brought to mind the frozen-over ribcage of a recently excavated T. Rex.

Footing in places was unpredictable at best. Trail running typically demands that your eyes constantly scan the ground two steps ahead for your next foothold. But on King George Island, it also became necessary to anticipate several steps beyond that, as the course at several points became an exercise in “Choose Your Own Adventure”: foot-deep powdered snow to your left, slushy ice straight ahead or a seemingly frozen-over stretch to your right. The demand for constant vigilance gradually took a mental and physical toll and led to lapses in attention, resulting in either (best-case scenario) choosing the more difficult and treacherous route, or (worst-case scenario) a hard and jarring fall on slick rocky terrain.

Just a boy and his balaclava, out for a springtime jog

And fall people did: this edition of the Antarctica Marathon might appropriately have been subtitled “There Will Be Blood”. Many runners fell multiple times, sustaining scrapes and bruises of varying severity. Two women broke their falls with their faces, yet soldiered on with impressive battle wounds that testified to their toughness. Luckily, I heard no stories of broken bones or more serious injuries. I was among the fortunate few to speak of “fall” rather than “falls” – I got too aggressive and lost my footing during my second loop of that first out-and-back, landing on my backside and bouncing right back up again. No blood, no foul. But in homage to March Madness going on back in the states, I adopted a mantra of “survive and advance” that served me well at all remaining icy stretches.

Although the prevailing concern had been shoe-sucking stretches of gooey mud, as it turned out postponing the trip until late March (i.e. closer to winter) meant that most of the would-be muddy bits were now iced over. Every once in a while I’d hit a slushy patch and submerge my foot, though fortunately wet feet never became a concern. I think by mile 4, most runners – myself included – gladly would have swapped the ice we had for the mud we didn’t.

Whether it was due to the half-week spent on the ship, or my racing in lower-body layers for the first time ever, I could quickly tell that on this day my legs wouldn’t be their trail-running best. Fortunately I wouldn’t need them to be – this wasn’t the Chicago Marathon, and the only PR to come out of this day would be Thom’s post-race press release. I’d run (and specifically trained) on tired legs many times before… the question wasn’t whether I’d finish, it was whether I’d do so before the other 40-something-year-old males on the course.

(Top) Overall winner Alan Nawoj leads the way up another icy hill (photo credit Anita Allen);

(Bottom) Third-place finisher & women’s champ Inez Haagen appropriately sports bib #1

Whereas the first 4+-mile stretch out to the Uruguayan base and back was fairly brutal (though with a striking glacier view to distract the mind), the second out-and-back was much more manageable. After a mile or so of smooth footing on dirt, a series of undulating hills led past the Chilean base and out to the second turnaround near the Chinese base, where yoga guru Liz sat waiting to cheer us on. Her enthusiasm was a welcome pick-me-up.

With one iteration of the course under my belt, I shed my balaclava and passed through the start/finish area to a chorus of cheers from the most amazing volunteer contingent on the continent. And as soon as I began my second ascent of that first nasty hill, the assorted aches and pains that had nagged me throughout the first nine miles faded – the lifelessness in my legs, the tightness in my left adductor, the overstretching of my arch that comes and goes in my Mix Masters. Even the Patch-induced fog around my head lifted… maybe I’d succeeded in sweating out the residual scopolamine. In any case, it all vanished. And finally I was back to doing what I do – I was running. On rugged trails, and up and down hills. In one of the most mythical and breathtaking places on the planet. Life was good.

Gentoo-men, start your engines! Footage with narration by Martin Evans on the marathon course (thanks, Martin!):

Not that I was running every step with my arms raised and fists pumped. To be sure, I was enjoying and appreciating the scenery of the course, stopping briefly to breathe in the views and snap a few photos along the first two out-and-backs. But other runners did a much better job of flipping their switch to carpe diem mode. Luckily the course layout was motivating for the frequent opportunities it afforded me to see my fellow runners. Because everyone seemed to be having (cue Dirty Dancing soundtrack) the time of their lives – even the lead runners greeted passing runners with a smile and a wave. Although in passing, I did overhear one of several marathoners with a cold-weather Canadian pedigree admit, “I wish I could fast-forward the next three hours.”

Some fatigued runners inevitably narrowed their focus later in the race to conserve energy; after the 17-mile mark, for example, I acknowledged and encouraged everyone I passed with the same silent thumbs-up. But a surprising number of runners I passed during my final out-and-backs still looked like kids riding a roller coaster for the first time – eyes wide, arms raised, huge grins seemingly painted Joker-style across their faces (Why so serious?, their body language seemed to ask). I admired and respected their live-in-the-moment mindset, in part because I couldn’t relate to it. The faster I run a race the more I enjoy it, with few exceptions (I can’t think of one right now). My overall enjoyment of a race is, in large part, a function of how long it takes me to get to the finish line. I realize expectations change, often in ways we can’t predict, and I know it won’t always be this way… but for now it is. I can live with that.

We interrupt this running program for some polar humor

Regardless of continent, no trail race would feel official without my taking a wrong turn. Despite Thom’s clear warnings to stay watchful for arrow signs and not blindly follow the person ahead of us, I unwittingly slipped into auto-pilot mode during mile 14 and blindly followed the person ahead of me. Ginger, who had recently passed me and was running a strong race, blew by the Chilean airstrip and had almost reached the base itself before realizing that neither the Chilean airstrip nor that large red building on her left was part of the course. I’d just reached the airstrip when she turned to look over her shoulder, and I gestured in sweeping windmill-type motions for her to turn around. Fortunately she did, and as I reversed course I saw yet another runner on auto-pilot heading our way. Retracing my steps to the suspect turn, I continued on my way and within minutes was passed by Ginger again, this time for good.

And that’s the story of how I turned this into my own personal 26.5-mile Antarctica Ultramarathon. And yes, there was a runner named Ginger on Gilligan’s ship, as well as at least one (assistant) professor.

By my third time around the course the temperature had begun to drop, and the icy uphill stretches along miles 18 and 19 had refrozen and become even trickier to negotiate. This third out-and-back to the Uruguayan base was the low point of my race, as reflected by the uninspired 13:07 it took me to complete mile 19. Did you run in Crocs?, I could hear the peanut gallery back home asking.

The official Last Marathon aid station

Once I passed through the start/finish area for the final time and approached mile 22, I could see – check that, feel – the light at the end of this tunnel. As the course approached its final uphill at mile 24.5, I was able to push the pace enough to pass two runners (was he in my age group?) who looked – as I had felt 5 miles earlier – to be running out of gas. Surging down the final stretch past the Russian base, I felt that unmistakable sensation of “this is why I run” wash over me as Katie and her fantastic fellow supporters cheered me across the finish line in a time of 4:29:50.

The raw, electric thrill of accomplishment overwhelmed me as I embraced Katie and then my fellow Mike from California, with whom I’d trained in Buenos Aires and who had run an inspired race, finishing fifth overall in a time of 4:20:26. One of the younger volunteers handed me a medal still folded up in its plastic bag, which was perfectly fine with me – by that point he could have handed me a lump of frozen penguin guano and I would have thanked him giddily.

Lookin’ for someone to hug after just missing a Boston qualifier by a mere 1:14:50

After hanging around the finish area to bask in the moment, take a few photos and cheer across the next two finishers, Thom encouraged me to change out of my wet running gear and into dry clothes. And as soon as I pulled on a dry base layer, I could feel my body temperature start to drop. My shiver reflex kicked in, and the feeling drained from my fingers and toes as I hurried to don my cold-weather gear. Ewan of the One Ocean crew sprang into action, jamming hand warmers into my gloves, zipping me into my parka and Wet Suit (since my fingers had lost all dexterity), and directing Katie and me to a waiting zodiac. As I’d later learn, Thom and the One Ocean staff were carefully monitoring all finishers after marathon winner Alan and runner-up Billy each ended up in the Russian medical tent with hypothermia.

Whether it was the warm glow of accomplishment, or more likely the dry clothes and hand warmers, by the time the zodiac reached the ship my body temperature had self-regulated. Maybe, as I’ve referenced before, I really am chasing the endorphin dragon. But if I could just bottle the pride and elation that gripped me as I crossed that finish line….

Instead, I settled for five blissful minutes in the Vavilov sauna, followed by a hot shower that, if it didn’t quite bring me back to life, at least made me feel a lot less undead.

Admittedly I was too euphoric to check, but I’m pretty sure that’s Katie inside that Antarctic sumo suit

(photo credit Anita Allen)

The Vavilov continued its spiritual rebirth as more and more runners returned with stories to tell, memories to share, and wounds to heal. Some of these wounds would be psychological, as with the dozen or so runners who found themselves unable to complete the marathon and were credited with the half marathon instead. And 78-year-old Wes, appropriately fearful of falling, walked off the course for the first time in his 201 marathons. Runners – particularly runners willing to travel to the end of the earth – are understandably a proud bunch, but hopefully all bruised egos, like their physical counterparts, will heal with time.

When the dust settled, 60 of the 72 runners who started the marathon, finished. This may sound harsh or arrogant, though that’s not my intent – but the truth is, there’s a lot to be said for a race that not everyone finishes. Inextricably wrapped up in its unsurpassed beauty is the harsh reality that Antarctica is a brutal, unforgiving backdrop for any activity, much less a marathon. You can admire and respect it from afar, you can agree to its singular demands, you can formulate the best-laid plan to overcome it. But at the end of the day you don’t choose this race, it chooses you.

Joao’s prediction had been correct, of course; with the race in our stern-view mirror, the mood aboard the Vavilov lightened considerably. But the revival wouldn’t be immediate, and the bar/lounge would masquerade as a quiet zone for one more evening while the rest of the ship surrendered itself to the inexorable force of post-marathon exhaustion.

Even without the icy patches, the undulating course would have left a lasting impression

To the victors go the handshakes: BBQ and awards ceremony (Sunday, March 31)

Official results weren’t immediately posted, so as Sunday afternoon rolled around I wasn’t sure where I’d finished overall or whether I’d placed in my age group. I knew the top five finishers, but beyond that I was in the dark as to who finished where, much less how old anyone was. I knew that Winter, who’d finished shortly after me, was 14 years old, but that was pretty much the extent of what I knew.

So I was looking forward to the world’s frostiest BBQ and awards ceremony that afternoon on the ship’s third deck. The food choices – who can say no to macaroni and cheese? – were excellent, the drinks were on ice (seriously, they were on ice), and after lunch had been served Thom stepped to the microphone to present the awards. Rather than having a prepared list of winners, he seemed to collate the overall results in his head on the fly, and there were long pauses – and the occasional incorrect winner announced – as he arranged each set of age group winners in his head before making the call. Standing on that deck, I was glad I’d invested in a kick-ass parka. Thanks, Patagonia.

Thom (center) congratulates me and Maarten Vroom (great running surname!) on winning the men’s 40-49 division

Alan Nawoj (33) from Boston was the overall marathon winner in an astonishing time of 3:29:56. Billy Nel (27) from Australia finished second with his own crazy-fast time of 3:37:48. And Inez Haagen (49) from the Netherlands, the first women’s finisher who has now won five marathons on five continents, rounded out the sub-4:00 finishers (and won the “non-hypothermic finishers” subdivision) with an impressive 3:41:52. Amazingly, Inez accomplished this mind-boggling feat at age 49, a number I had to read three or four times on the overall results page and which I still don’t actually believe. Among the runners, I particularly enjoyed watching her and Alan as we passed along the course – each has a smooth, flowing stride that even gravel-strewn patches of black ice couldn’t suppress.

Winter ran a strong race of her own, crossing the finish line in 4:49:45 and seizing the title of youngest runner to complete a marathon on the White Continent. As such, she remains on track to conquer her larger goal of becoming the youngest runner to finish a marathon on all seven continents before she turns 15 next year. And more importantly, she’ll raise a whole lot of money for prostate cancer research while doing it.

Despite finishing a solid hour (actually 00:59:54) behind Alan, I managed to win the men’s 40-49 age group in 4:29:50. In fact, all three Mikes on the roster – me, Mike Hess (34) and Mike Ahrens (62) – won our age group. ‘Tis a powerful and athletic name, that one. As their name was called, each winner stepped to the front to receive their award: a handshake from and photo op with Thom. This was, needless to say, the source of some playfully snide commentary from several age group winners, who’d clearly been hoping for something more, well, medal-y.

Thom with the top 3 women finishers: (left to right) Ginger, Winter and Inez

The awards ceremony culminated with the presentation of Seven Continents Club medals to those 17 marathoners and half-marathoners for whom Antarctica had been their 7th racing continent. That was, fittingly, one proud and beaming group. Like the Antarctica Marathon itself, the Seven Continents Club was Thom’s brainchild. As a runner I’d known of the Club for some time, but only recently did I become truly cognizant of its existence. My own motivation for wanting to race in Antarctica was my twin desire to (a) visit Antarctica, and (b) race in every compelling locale we visit. The Seven Continents Club provides the appealing opportunity to race in places we’re already inclined to visit, as well as in some intriguing, out-of-the-way settings we might not otherwise consider. I can definitely envision myself as a member of the Club someday.

The Last Great Continent (Sun – Tues, March 31 – April 2)

Once the marathon ended and the Vavilov left King George Island behind, our collective stress melted away – and for once, Antarctic thawing was a good thing. Wes’s sweatshirt spoke for nearly everyone with its proclamation of “GOOD-BYE TENSION, HELLO PENSION”. People animatedly recapped their race day from start to finish and swapped stories from the course. Runner-up Billy claimed the marathon “makes Comrades look like a baby,” a comment quickly dismissed by Comrades veterans Rory and Billy’s father Pieter. Jeff from Manhattan Beach summarized his thoughts succinctly, saying he felt “like I was beaten with a stick.” And still others compared (and re-bandaged) open wounds.

For the remainder of our trip, we’d have the opportunity to stash our running shoes and immerse ourselves in Antarctica. And for those who have yet to visit, the best description I can manage is “nature porn.” Every stark, pristine landscape looks as though it were professionally airbrushed for maximal effect – visual features, textures and lighting coalesce in seemingly unreal ways. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart might just as easily have been a naturalist talking about the Antarctic wilderness when he wrote, “I can’t define pornography, but I know it when I see it.”

Over the next three days we would:

- witness unique, dramatically lit landscapes – deep blue icebergs framed against a backdrop of solid gray skies and unblemished white peaks – that looked more like Superman’s home planet of Krypton than unspoiled nature. Staring up from the quiet of our floating zodiac at the exquisitely oriented layers of ice and snow, it was mind-boggling to think these layers had been accumulating, building to their present-day dimensions, unperturbed for… ever? Plus or minus a few thousand years.

- visit Gentoo penguin rookeries (and sighted Adelie and Chinstrap penguins) in Mikkelsen Harbor and on Cuverville Island. Like most of the group I was fascinated by these goofy-looking, -sounding and -acting birds, many of whom passed their days conserving energy while waiting – in a race against time – for their swimming feathers to replace their down covering.

- experience some of the most awe-inspiring moments of our lives in Neko Harbour and Fournier Bay, courtesy of breaching minke whales and several intimate encounters with humpback whales. The humpbacks curiously chose to stay and socialize with our kayaks and zodiacs, either of which the whales easily could have flipped had they been of the mind to do so. To appreciate the combination of power, grace and empathy that the humpback embodies, check out the video below that I filmed from our zodiac.

- get up-close and personal with Weddell seals, Antarctic fur seals, crabeater seals, and even a leopard (penguin-munching) seal. They may not get the attention afforded their whale and penguin brethren, but the Antarctic seals never ceased to amaze and amuse.

- hear Assistant Expedition Leader Mark – check that, Maahk – entertain and fire up his audience with his account of how an encounter with a humpback whale – and looking the gentle creature right in the eye – changed his life. Mark was like a man possessed as he told his story: he was animated, he was jazzed, he was pumped, and you couldn’t help but be inspired by his energy and sense of purpose.

Antarctica is a land so completely devoid of artificial noise – no distant voices, no traffic, no machinery, no hum of electric power lines – that you soon realize: every sound out here matters. And it’s worth your time to listen. No static, no background noise, only nature as it has been for thousands of years. What you see is what you get, and if you don’t like what you see… well, Antarctica doesn’t care. And it’s not changing for anyone.

When I say “Antarctica,” chances are you think “cold.” And yes, admittedly it’s cold down here. But if you’re willing to close your mouth, open your mind and embrace your insignificance, then air temperature won’t be your lasting memory of this place. Because that’s what this continent asks of its guests: feel free to keep your muddy boots on, but leave your first-world problems at the door. In subtle, sublime ways that extend beyond the forced reality of the Drake Passage, Antarctica is a land of shifting perspectives.

The many faces of penguins (clockwise from upper left): fat and contemplative, fat and curious, fat and proud, fat and frenzied

On the evening of our final full day in Antarctica, John Bingham hosted a live auction to benefit Oceanites, a non-profit science and educational foundation that collects data for the Antarctic Site Inventory. Oceanites recently lost their National Science Foundation funding and one-third of their total funding when the Sequester kicked in. All proceeds from our auction would go to benefit Oceanites, and runners answered the call with generous and in some cases above-and-beyond contributions. John started fast at a decidedly un-penguin-like pace, kicked it into gear – “I told ‘em I could have us out of here in 30 minutes!” – and in no time flat had found homes for mile markers 1, 13 and 26; the start/finish line banner; a “one-of-a-kind” (turns out there were two) nautical chart of our voyage; an author-autographed biography of Frank Wild, Ernest Shackleton’s right-hand man; and the opportunity to present the wake-up announcements over the ship’s PA on the final morning of our journey.

I took advantage of the silent part of the auction to score mile marker 20, a nice round number that to me signifies a key milestone in every marathon effort.

(Left) Auctioneer John Bingham raises money for Oceanites as Jenny Hadfield tracks the results (photo credit Maarten Vroom); (Right) The closest I’d come to taking home a penguin

Queasy come, queasy go (Wed – Fri, April 3 – 5)

During the auction and dinner that evening, the Drake Passage flexed its muscles once again as we bid the White Continent goodbye and set our sights once again on Ushuaia. Quickly picking up where it had left off, the Drake rocked the ship with renewed ferocity – silverware clattered to the floor in the kitchen, diners had to side-step broken glass, occupied chairs slid several feet across the dining hall floor (much to the horror of the adults and the delight of the kids), and before dessert was served, half of those seated at our table had excused themselves to go lie down.

By 10:00pm the Vavilov resembled an abandoned ghost ship as people hunkered down in their cabins to ride out the “Drake Shake.”

Looking to preserve our vision during the return voyage, Katie and I both chose to forego the Transderm patch in favor of Dramamine, which worked well for me at a dose of one pill every 12 hours. No drowsiness, no blurred vision and no seasickness. Howl as it might outside the portholes in our cabin, the Drake would have to look elsewhere for easy prey.

Coming together with like-minded folks like Rory, a 12-time Comrades Marathon finisher,

was a highlight of the trip

But life on the Vavilov those two days was anything but comfortable. As near-hurricane force winds buffeted the ship, the theater that played out from our front-row seats on the bridge could well have been Mother Nature’s production of “The Sound and the Fury.” And again I felt very, very small. Credit to the One Ocean staff, they tried to keep our minds occupied… but even if you’re not prone to motion sickness, it’s hard to keep your head in the game when the world is constantly shifting beneath your feet. With the ship rising and falling unpredictably I felt like a human accordion: tall and stretched-out one second, short and compact the next.

But even the Drake couldn’t stifle all productivity. Fortunately I had the opportunity during this time to sit and talk shop for a few minutes with Jenny Hadfield. And I’m glad I did – her professional voice of experience was graciously shared and greatly appreciated. I had questions about writing and blogging, and she shared her own story of how she’d gotten started in the exercise physiology field and had gradually transitioned to a now-successful writing career (her popular advice column “Ask Coach Jenny” offers training tips and can be found on the Runner’s World website). She’s not only a terrific professional resource but also, like nearly everyone I met on the Vavilov, a genuine and thoughtful person.

We were all urged to submit our ten best Antarctica photos, and that evening Nate the great photographer of the One Ocean staff presented a slideshow he’d compiled (in record time) from our selected images. Complete with its own soundtrack, the slideshow was a tour de force that alternately had the audience laughing, cheering, ooh-ing and aah-ing. Best of all, the One Ocean staff provided each passenger with a USB jump drive containing – among other info – the slideshow, daily newsletters, staff bios, nautical briefing logs and spreadsheet of wildlife sightings from the previous ten days. I probably should have saved myself (and you) a lot of time by just posting all the data from that jump drive in place of this recap.

They may seem bumbly fumbly stumbly on land, but… proceed to perceive a pleasing pack of porpoising penguins:

It’s been ice to meet you (Fri – Sat, April 5 – 6)

Our voyage culminated that evening with the Captain’s Dinner – salmon, hooray! – in which the Captain of the Vavilov was appropriately recognized by all and presented with a marathon finisher’s medal by Thom. Throughout the meal glasses were raised, gratitude was expressed, egos were stroked and the microphone rarely sat silent. Thom invited Winter to say a few words and she acquitted herself well, reminding us about Team Winter and urging everyone to commit their running to a cause important to them.

After dinner we set about trying to repack our once-efficiently crammed bags, a task that felt like trying to shove toothpaste back in the tube. And the next morning we awoke before the sun in Ushuaia, where we began the dual process of reacclimating to civilization and saying our sentimental goodbyes. Sadly, I realize some folks I’ll never see again, though my cyber-stalking skills will stay sharp. But the world isn’t big enough to contain these runners’ passion for their sport, and I look forward to (pun intended) running into some of them again in other states, in other countries and on other continents.

Katie knows how to pick her running battles (Ushuaia)

Clearly Antarctica was a life-changing whirlwind of firsts and lasts. And add one more to that list: it was the first time we’d traveled with a group of highly motivated, like-minded athletes… though hopefully it won’t be the last. Opportunities like this one don’t knock – or in this case email – very often. My thanks to Thom Gilligan and an anonymous iceberg with paint streaks on it floating somewhere in the Southern Ocean.

Eventually, 38 hours after last waking up on the Vavilov – and following a 3-hour delay in Ushuaia, 3½-hour flight to Buenos Aires, 4½-hour layover in Buenos Aires, 11-hour flight to Dallas/Fort Worth, 3½-hour layover in DFW (1½ hours once we cleared customs and security), 4-hour flight to San Francisco, one-hour train ride to downtown Berkeley and one-mile walk with our bags slung over our shoulders or trailing behind us – we found ourselves standing, exhausted but triumphant, on the doorstep where we’d started Mike and Katie’s excellent adventure 17 days earlier. Climbing the short flight of stairs inside our front door, I dropped my bags on the top step and exhaled for what felt like the first time since Argentina. Then I did what I always do when I don’t know what to do next.

I went for a run.

The sun rises over Ushuaia and sets on our Antarctica adventure

BOTTOM LINE: Assuming I’m talking to running enthusiasts here, my summary statement is simple: run the Antarctica Marathon at least once in your life. Unless of course you’re a compulsive type-A personality (and running attracts them like no other sport) who hates surprises, then you might want to skip this race.

It’s not an inexpensive outing, but that’s hardly surprising… you get what you pay for.

Was it the most challenging race I’ve run? No, that distinction still belongs to last year’s sunbaked Mount Diablo Trails Challenge 50K. But it was certainly challenging enough. Preparation-wise, it’s important to bear in mind that the Antarctica Marathon is a bona fide trail race, which places it outside many runners’ comfort zone. Unfortunately, if you want to race on this continent it’s not as though you have a slew of choices – you can’t just opt for the road version of the marathon. Sensible expectations will go a long way toward optimizing your Antarctica Marathon experience.

PRODUCTION: Thom and his Marathon Tours crew of Scott, Anita, John and Jenny did a commendable job of orchestrating all aspects of the Antarctica Marathon – from regrouping on the fly after the Great Iceberg Attack of ’13 to their near-flawless race day execution. I certainly didn’t envy them their pre-race field trip over to King George Island to set up the course, with subfreezing gale-force winds blasting them in the face while they struggled to pound each marker stake through several inches of surface ice. But set it up they did, and come race day the course was well marked (my own personal detour notwithstanding) and pretty much dead-on accurate at 26.2 ± 0.1 miles.

Other companies have hurried to cash in on the demand from runners seeking to run a marathon at the bottom of the world. But no other company can boast Thom’s breadth of experience and connections in Antarctica. At least two companies offer a one-day Antarctica experience in which they fly into King George Island, immediately organize a marathon and then fly out the same day. To me that would feel like scoring tickets to the Super Bowl, showing up at the stadium and then watching the game on the TVs in the concourse. Sure you could say you were there… but were you really there?

Apparently my expert editor on all things Antarctica grew tired of penguin pictures

My main critique of the Antarctica race experience would be the post-race awards. For example, the finisher’s medal should vary from year to year, and should always include the year of the race (or barring that, complementary engraving on the back of the medal that includes name, finish time and year). There’s no excuse for the fact that the Antarctica Marathon medal has remained the same for at least six straight years now (dating back to the image I found online of the same medal from the 2008 race). This is particularly true when you’re hosting a group of dedicated, goal-oriented runners, many of them 50 States/Seven Continents Club members for whom race bling is all-important, and deservedly so.

In addition, it would be nice if age-group winners merited distinct medals – for example, a penguin holding up one flipper or two to signify first or second place – to accompany the handshake and photo-op that currently await them. I’d be happy to receive one retroactively. I feel like these are easily implemented suggestions that would enhance the race experience, even in Antarctica.

Overall, given their professionalism and intimate knowledge of the running community, together with their catalog of compelling international marathons, I look forward to traveling with Thom and his Marathon Tours crew again.

Liz of OOE secures a kayaker, then requests a rowing implement with the order to “Paddle me!”

But in the end, the One Ocean Expeditions staff (and the largely unseen Russian crew members of the Vavilov) were the stars of this show. Andrew and his 12-person staff did everything in their power to ensure our Antarctica experience met – and in most cases exceeded – expectations. Without exception, every member of the OOE staff was highly competent, professional, knowledgeable, experienced, entertaining, happy to answer questions and just plain fun to be around. Granted I haven’t traveled to Antarctica with any other cruise company, but I can recommend OOE without reservation. Based on conversations with and body language of other passengers, I’m confident the vast majority would echo my thoughts.

As with any successful race, the volunteers were a key element of the Antarctica Marathon. No doubt I wasn’t the most happy-go-lucky and responsive runner out on the course – and they had to see me six times in my 4½ hours – but Kathy and her crew (Katie, Sharon, Sally, Wayne and company) stood by the start/finish line for the ENTIRE race, and were there to cheer emphatically and shout their support after every out-and-back. I never dreamed that Katie would willingly – and dare I say happily – stand idly outside in Antarctica for five hours. Yet there she was, smiling broadly and cheering loudly every time I passed. Kudos to her solid layering strategery, Arctic Parka and Wet Skin for keeping her toasty and for inspiring that kind of gumption.

Rating the Antarctica Marathon experience based on the race t-shirt feels a bit like rating a 5-star restaurant based on the embroidery of the napkins. But since I’m clearly not one to cut corners in recapping a race, here goes: the t-shirt is nice. Very nice. And colorful, as long as you’re a fan of baby blue. It’s a high-quality tech t-shirt with mesh shoulder and side panels. And if you happen to like the Antarctica Marathon logo emblazoned on the back, then you’re in luck, because the Marathon Tours crew has an assortment of race-related apparel available for purchase in Buenos Aires and on their website.

For other (more concise) perspectives, check out Jenny Hadfield’s “10 Reasons to Run the Antarctica Marathon” on the Runner’s World website, as well as Winter’s report on “A World Record in Antarctica, and Much More” at Athleta.net.

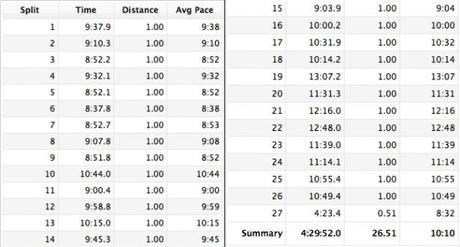

FINAL STATS:

26.5 miles (including an unplanned 0.3-mile detour) on King George Island, Antarctica

Finish time & pace: 4:29:50 (first time running in Antarctica), 10:10/mile

Finish place: 8/60 overall (73 starters), 1/10 in M(40-49) age group

Race weather: penguin-pleasing cold, low winds (starting temps in the low 20s)

Elevation change (Garmin Connect software): 2,023ft ascent, 2,031ft descent

For a race in which my major concern was NOT doing the splits, these aren’t so awful