The human face evolved to take a punch! That’s the interesting (and slightly out-there) claim researchers made yesterday. And like many interesting (and slightly-out there) ideas it was gobbled up by the press; with articles about it appearing at the Guardian, BBC, phys.org and many more. But is there any merit to this claim?

Difficult to say based on news reports as they contain scant information about how these scientists actually arrived at this conclusion (do they ever?). Fortunately, with a little help from the internet, I was able to dig up the research paper which started all this (and is available for free, if you want to read along at home). And after reading it I feel confident in saying: nope. They provide no compelling reason to think that the human face evolved to withstand a punch.

The dumbest thing you will read about human evolution this week. "Human faces evolved to be punched by human fists" j.mp/1pvFiUF—

Eric Michael Johnson (@ericmjohnson) June 09, 2014

The research revolves around grade 2 & 3 hominins; which lived from around 4 million years ago until ~2 million years ago. These were the members of our family that first began to spend a lot of time walking upright on the ground. However, as well as the evolutionary changes one might expect to see in animals becoming more reliant on bipedalism, their skulls underwent some significant changes too.

They become much more robust; with large, thick bones. Their jaws in particular became especially powerful, in some species reaching crazy extremes that gave them a more powerful bite (relatively speaking) than any living ape1. These jaws could also explain the robusticity in other parts of the skull, as it would have provided an anchor for powerful chewing muscles and/or reinforcement against these huge force2. Based on all this most people concluded that these weirdly powerful skulls were adaptations to a diet that would require a lot of chewing (a conclusion supported by the fact their diet does appear to have involved a lot of chewing3).

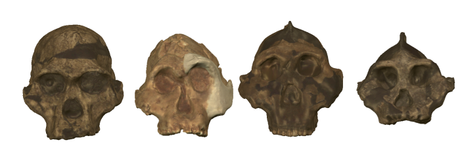

The really robust skulls seen in these hominins. From left to right: Australopithecus africanus, Paranthropus robustus, Paranthropus boisei, Paranthropus aethiopicus. Note: none of these are thought to be direct ancestors of humans

However, the face-punch-paper begs to differ; arguing that there are some things this whole “diet” idea can’t explain.

- Why do these skulls differ between the sexes? After all, both surely had the same diet

- Many parts of the skull that became robust experience relatively limited forces during chewing.

- Aside from Paranthropus robustus and Paranthropus boisei, there’s no evidence the other species ate hard/tough food.

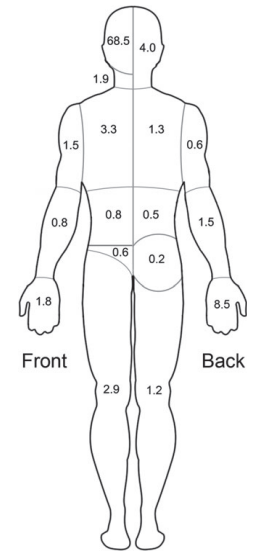

Instead they point out that during unarmed fights it is the face that typically gets hit the most. In fact, in many American hospitals fisticuffs is the leading cause of injury to the face; causing a greater portion than even car accidents. So they posit that these robust skulls are actually an adaptation to this sort of injury, helping to reduce it. And from there they really run with the idea.

Where people get injured in fights

The powerful chewing muscles, for example, aren’t to chew; they act as padding to protect the skull. The large teeth aren’t to transfer the force of chewing to food, but to transfer the force of being punched in the jaw to the rest of the skull; spreading it over a wider area and reducing the damage. The differences between the sexes are because it was men who were getting into fights. The bits of the skull that became robust that weren’t linked to chewing are often damaged in fights, hence why they got bigger and stronger.

But all of these amount to a “just so” story. As the space-ape saga shows; it’s easy to cherry pick evidence to fit almost any conclusion. When you boil it down their entire thesis rests on the assumption that (a) fighting was a significant evolutionary force in these hominins and (b) that fighting was similar enough to how modern Americans fight that it routinely resulted in similar injuries. However, at no point to they give evidence that those two assumptions are valid.

They point to no injuries in fossils that might indicate these hominins were fighting. They provide no evidence from their anatomy that suggest they would fight similar to how modern humans do (aside from the fact that they could form a fist). Nothing about how other primates fight suggest that these would be important factors either. Chimps, for example, are one of the most aggressive apes yet their fights rarely result in injuries (and when they do they’re typically to the hands4).

Not that all this means our ancestors weren’t fighting, just that without any additional evidence confirming these basic assumptions, the entire idea that the human face evolved to survive fights comes crashing down. It’s just an assertion; and not much else.

But about their criticism of the diet hypothesis? Well I don’t think they hold much water either. This could be the topic of an entire other post, but briefly speaking:

- The sexual dimorphism of these species falls within the range of variation seen in living apes, who don’t punch each other in the face (and have the same diet to boot5)

- Individual bones of the skull don’t appear to evolve independently. Instead they evolve as a unit, so bones which might not play a huge role in eating would still change if other bones were.

- For P. aethopicus, it’s not like we’ve looked at their diet and found that they didn’t eat hard/tough stuff. There’s just very little information on their diet to begin with. For the other species for which there is no evidence of eating hard/tough food, Au. africanus, it appears that the premolars would play the biggest role in chewing it. Yet research has focused on the molars6.

In other words, the preponderance of evidence indicates that these members of our family had weird faces to deal with a weird diet. The idea that it was actually an adaptation to fighting is based on assumptions for which no evidence is provided.

References

- Demes, B., & Creel, N. (1988). Bite force, diet, and cranial morphology of fossil hominids. Journal of Human Evolution, 17(7), 657-670.

- Wood, B., & Constantino, P. (2007). Paranthropus boisei: fifty years of evidence and analysis. American journal of physical anthropology, 134(S45), 106-132.

- Constantino, P. J., Lee, J. J. W., Chai, H., Zipfel, B., Ziscovici, C., Lawn, B. R., & Lucas, P. W. (2010). Tooth chipping can reveal the diet and bite forces of fossil hominins. Biology letters, 6(6), 826-829.

- de Waal, F. (1986). The brutal elimination of a rival among captive male chimpanzees. Ethology and Sociobiology, 7(3), 237-251.

- Wood, B., & Lieberman, D. E. (2001). Craniodental variation in Paranthropus boisei: a developmental and functional perspective. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 116(1), 13-25.

- Strait, D. S., Weber, G. W., Neubauer, S., Chalk, J., Richmond, B. G., Lucas, P. W., … & Smith, A. L. (2009). The feeding biomechanics and dietary ecology of Australopithecus africanus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(7), 2124-2129.