Spoilers For The Hitcher Below

Don't you just hate it when bad narrative decisions happen to otherwise good movies? Whether its Source Code losing complete track of its own premise, Shutter Island falling back on one of the oldest cliches in the book, or Don't Breathe deciding it suddenly needs a turkey baster ex machina, there's a real "I'm not mad, I'm just disappointed" energy to watching a film stumble at the goal line. Bad movies come and go. Great movies are from a rarer breed. It's the in-between group that vexes the most because of all the unrealized potential.

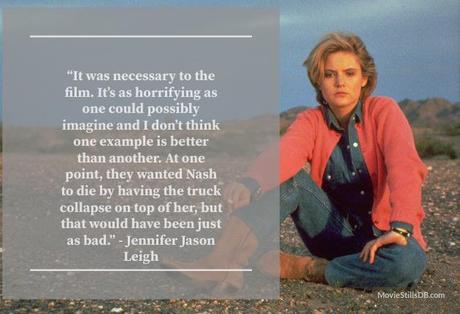

I can't decide which group The Hitcher - Robert Harmon's 1986 cult classic - belongs to. For the most part, it's a well-acted, thoughtfully-filmed, truly inspired thriller that plays like Mad Max by way of Duel and Strangers on a Train. There are some next-level car stunts, some of the best of any 80s action-fest not made in Australia. It comes equipped with a fantastic synth score from composer Mark Isham. Just when you think you can dismiss the story as standard exploitation fare, a breathtaking shot comes along to catch you off guard. For example, a stray car light surprisingly illuminates Rutger Hauer's face as he lurks in the shadows of a motel room and looks over a sleeping Jennifer Jason Leigh, oblivious to the imminent danger. (The cinematographer, John Seale, later won an Oscar for The English Patient.)

But then, spoiler, the only female character of note has to die. Gruesomely. Yet, you never see the actual gore. It's the - spoiler from 1995 here - Gwyneth Paltrow's Head in a Box concept executed a decade earlier, a death trap scenario Jigsaw would be proud to call his own. Truly disturbing stuff.

But is it actually necessary? How do we cope with fridging these days?

He's Just No Good and He Never Will Be

The Hitcher breaks so many screenwriting rules. Neither the protagonist nor the villain receives any real backstory. The inciting incident - while driving across West Texas, Jim Halsey (C. Thomas Howell) picks up a hitchhiker who calls himself John Ryder (a terrifying Rutger Hauer) and turns out to be a serial killer if not maybe just evil personified - happens in the first five minutes. Nearly all of the killing occurs off-screen, and then when the biggest death of all arrives the camera captures every excruciating second leading up to the kill before cutting to black at the last moment. The villain's motive is never spelled out for the audience, and the story ends immediately after the good and bad guy fight to the death, with the victor draped in a twilight hour backdrop as the credits mournfully roll over the image. To the bitter end, it's a film that wears nihilism like a coat of armor.

To some, all of these decisions are reasons to hate The Hitcher. Roger Ebert sure did, writing in The Chicago Sun-Times, "But on its own terms, this movie is diseased and corrupt. I would have admired it more if it had found the courage to acknowledge the real relationship it was portraying between Howell and Rutger, but no: It prefers to disguise itself as a violent thriller, and on that level it is reprehensible." To others, like C. Robert Cargill and Brian Salisbury of the Junkfood Cinema podcast, The Hitcher 's slightness of form is the key to its brilliance.

More films should be so easily summarized: a tired driver improbably thrawts a hitchhiker's murder attempt, but the Hitcher exacts his revenge by framing the driver for multiple murders. Also, he just generally fucks with him. If there's anything more to the story than that - Is The Hitcher trying to spiritually break Halsey like some West Texas variation of the biblical story of Job? Is it all because The Hitcher wants to die and for Jim to be the one to kill him? Is Halsey possibly already dead and The Hitcher some kind of ferryman figure with a sick sense of humor? - you have to decide for yourself.

This is all news to me. Before two days ago, I was only ever vaguely aware of The Hitcher's existence. For the longest time, I confused it with The Hitchiker, the 80s horror/thriller anthology series that was like Twilight Zone but with boobs. (Adding to my confusion: Beyond the obviously similar titles, The Hitcher and The Hitchiker were each produced by HBO.)

However, when a Facebook film club hosted a screening of The Hitcher at a local movie theater in honor of the late Rutger Hauer I was more than happy to attend. What I got was a tight 98-minutes of white-knuckled tension and gritter-than-expected horror. By jumping straight into its premise and refusing to ever relent after that, The Hitcher is a film that knows how to get to the damn fireworks factory. Then it blows up the factory and earns the equivalent of 5 stars on Grand Theft Auto just so it can shoot a helicopter down from the sky using nothing but a hand cannon.

To say The Hitcher's action and mayhemoccasionally strains credulity would be like saying Joaquin Phoenix kind of has a thing for rambling acceptance speeches. It's an understatement! However, all of the little practical questions that prop along the way - John Ryder might as well be The Terminator - actually enhance the terror for me, furthering the sense that The Hitcher is the manifestation of our worst nightmare.

Nash Fridgington

The problem is Nash. That's the name of Jennifer Jason Leigh's character, a small diner waitress who gets sucked into the human version of Duel playing out between Halsey and The Hitcher. We first meet her as she exits a bus on the way to her job, working at her family's diner despite harboring occasional thoughts of throwing caution to the wind and moving to California. Jim enters her life as a mysterious, gasoline-covered (it's complicated) man demanding to use the phone to call the cops. Against her better judgment, she lets him in, trusting that he's not some crazy killer. She even takes pity on him and cooks up a cheeseburger and fries, on the house.

Actually, to the film's credit, romance doesn't exactly bloom between the two. She simply takes pity on him because he has a trustworthy face, but minutes after their first meeting he's captured by the cops and hauled away, wrongly accused of The Hitcher's killing spree. They don't meet again until much later in the movie, at the end of her day and on her bus drive home where he attempts to take her hostage.

Pretty quickly, though, he gives himself up to the authorities, but they don't want to take him alive. They still think he's the real Hitcher, and when Nash observes a cop attempting to murder Halsey in cold blood - "You spit on me!" becomes a cover story for homicide - she springs to his defense. It's only then that she truly believes his cries of innocence. They end up fleeing together, and when The Hitcher actually shows his face and single-handedly eliminates all of the pursuing cop cars her fate becomes inexorably linked to Halsey's.

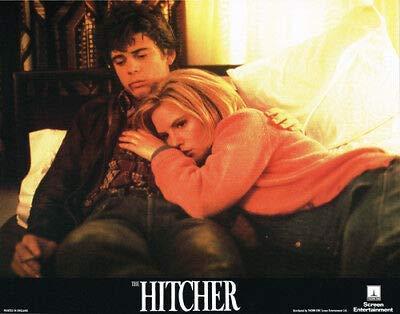

Understandably, she's terrified. When they finally get to a motel room, she doesn't kowtow to genre expectations and strip for a gratuitous sex scene. Instead, she merely rests her head on Halsey's chest out of a basic need for some human comfort, and later she finds a private moment to call her father and reassure him that she's ok. It's the last conversation she ever has.

What happens next was controversial from the get-go. Screenwriter Eric Red went to some truck drivers asked, "Well, look, if you wanted to kill a girl with a truck, how would you do it?" What they told him led to one of the most distressing - or at least bleakest - death scenes of the decade.

Backstory Time

The backstory here is Red - who once cited Straw Dogs, Taxi Driver, Dirty Harry and Duel as his favorite movies - was an aspiring filmmaker who had made a short he'd hoped to adapt into a feature. When that didn't happen, he moved to Austin, Texas and took a job driving expensive cars across the state from dealerships to new owners, the same job he gave Halsey in The Hitcher. At some point on one of those long drives, he came up with the idea for The Hitcher.

His first draft was longer (190 pages) and bloodier (a decapitation and an eyeball in a hamburger figured prominently) and would go on to be reworked by various producers, studio executives, and the director, but even in that embryonic stage, Red's script had a scene in which a girl is tied to a truck and a pole and gets torn in half. Through all stages of development and production, that remained his favorite moment in the story, as he told The Los Angeles Times, "It's a highly tense scene, it's very exciting when you do something like that."

"Exciting" to him, but nauseating to others. The script made its way around every studio in Hollywood, landing for a spell at Fox. It became a hot dinner party conversation piece, as Fox's former production vice president Carol Baum recalled, "I can't remember who was there-it was an industry-type dinner and somebody made a comment about the script. When I defended it, that person berated me for liking such a violent exploitation film."

Her bosses eventually cut ties with the project, but Baum told the LA Times that had Fox stuck with The Hitcher she would have made sure the ripping-apart scene was taken out.

Robert Harmon - a still photographer-turned-cinematographer with one short film to his name - was similarly berated by friends and colleagues for agreeing to direct The Hitcher. That was perhaps less specifically because of the ripping scene and more about the totality of the script's violence and suspicion that this would just be another slasher. Harmon's compromise was to reroute as much of the violence to off-screen as possible. As for the notorious ripping: "I never planned to show it on screen."

An 11th Hour Change of Heart

Harmon almost didn't even get to make that decision. When the project finally found a home at HBO/Silver Screen, a decree was sent down by the company's chairman/CEO Michael Fuchs: the girl would not be torn apart!

"We got into huge arguments," recalled Donna Dubrow, the woman most responsible for bringing The Hitcher to HBO. "[HBO Senior VP] Maurice [Singer] would say, 'The girl can't die.'

"I said, 'What is our story, then? What if Janet Leigh hadn't died (in "Psycho")? If she stays alive, I don't want to see that movie, because there won't be a movie."

Dubrow, recounting the exchange to the LA Times, added, "Then we would talk about her dying differently. I said, 'Maurice, give us some ideas. Put her up on a cross, wrap her around a tire.' They were preposterous thoughts, but they were trying to make her death not horrible, when-by the nature of the script-it had to be."

One potential compromise: shoot the death scene, but also add a funeral scene later. At least give Nash the dignity of a proper burial. Harmon's response: "Maybe I was a little too glib about things at that point, but I said that I would be happy to give her a funeral if I could do it with five caskets . . . or one very, very long one."

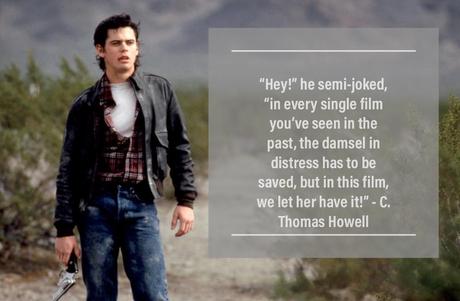

The people they cast to play out this little fantasy had similarly mixed - and in one particular case, glib - responses:

According to Fuchs: "They found a way to make a gruesome scene acceptable." Did they, though?

Through Modern Eyes

We are talking about a 1986 movie. Gail Simone didn't coin the phrase "fridging" until 1999 on her website Women in Refrigerators (WiR) and when she did it was only in reference to comic books, but the core concept applies here: a female character exists only to be killed and advance the arc of the male lead.

Of course, in-context Nash's death is part of the film's rather purposeful rule-breaking. As Harmon told Cinefantastique, " The Hitcher is a genre picture which breaks the expected rules of the genre." If we're playing by slasher rules, Nash has done nothing morally wrong to justify her death, and if we're going by thriller conventions when the girl gets tied to the proverbial train tracks at the climax of the story the hero is supposed to make it just in the nick of the time. Fridging is typically a first or second act plot motivator, not third - although as Se7en showed, it can come at the very end.

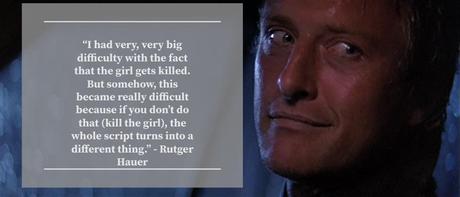

No one was thinking of such things in those terms back in 1986. Even then, however, they knew Nash's death was going to be the scene everyone talked about. As Ed Feldman, one of the film's producers, told The LA Times, "Rutger didn't want to do it; he thought he'd be the bad guy. I told him, 'You are the bad guy . . . and you'll be the baddest bad guy there ever was!'"

Interviewed by Starlog after the film's release, Hauer praised Bob Harmon's work as a first-time director and spoke of The Hitcher as hopefully his last hurrah playing the bad guy. (It stuck for a while, at least. He didn't play another traditional heavy for another half-decade.) Hauer loved the way the film trusts the audience to divine the killer's motivation, but as an actor, he had to come up with his own back story. The way he saw it: "[John Ryder] wants to get killed. He picks a specific guy to do the work. I guess he doesn't have the guts to kill himself. He makes a point of that - 'Look, I'm being killed'."

Hauer also said:

This is a reading - the first quote, not the E.T. one - I personally subscribe to. Countless times throughout the movie, The Hitcher could easily kill Halsey and chooses not to. Instead, his goal is to emotionally break the kid, so much so that Halsey will eventually have no choice but to fight back and kill the apparent devil. Tearing Nash in half is the most extreme motivator he has in his back pocket, and - spoiler - it works. Halsey does avenge Nash's death and leaves The Hitcher dead and bloody on the side of a highway. Cue credits.

Fridging Nash doesn't mean The Hitcher is automatically canceled. As Gail Simone herself once said about fridging, "WiR was never meant to be an indictment, it was meant to ask a question to provoke thought." Like the Bechdel Test, it's not a blanket indictment of every instance in which a female character dies so that a male character can grow. As Den of Geek's UK editor Rosie Fletcher told The Guardian two years ago, "It's more a test to see how often it happens: so often, a woman has to die or be tortured to facilitate a male's personal growth. That's when it becomes a problem, when we're seeing it all the time."

If anything, both our awareness of the trope and just how often it has happened since The Hitcher 's release lessens the dramatic impact of Nash's death. Perhaps in 1986, seeing a female character so heartlessly dispatched felt so shocking because it broke all the rules and didn't adhere to slasher norms of the era. (They made us imagine the death instead of showing it to us? Huh. That's a new one.) Today, however, oh, they killed the girl? Man, there's always a dead girl.

Then again, by the time The Hitcher arrived, it had been 12 years since Charles Bronson's Paul Kersey had avenged a wife and four since he'd avenged his daughter, the latter having been raped in two different Death Wish films before dying. So, yeah, this shit goes back a long way.

As The Guardian put it, "A healthy, nuanced discourse can point out bad things in good movies." What happens to Nash in The Hitcher is a bad thing, to put it lightly. The rest of the film is an overlooked gem.

Apparently, Platinum Dunes felt the same way.

The coda

The Hitcher franchise has been revived a couple of times and in each new iteration, the story was ultimately shifted toward a more standard slasher scenario with a madman-from-the-highway pursuing a final girl:

In 2003's direct-to-video effort The Hitcher II: I've Been Waiting, C. Thomas Howell reprises his role as Jim Halsey, but - spoiler - he takes an early exit from the story, killed off so that the new Hitcher played by Jake Busey can further terrorize Halsey's girlfriend played by Kari Wuhrer.

In 2007, Platinum Dunes cranked out a remake of the original. The plot is basically the same, to the point that Eric Red received screenplay credit despite having nothing to do with the project. Jim Halsey (Zachary Knighton) and John Ryder (Sean Bean) battle much as they had before. This time around, however, joining Jim on the journey is a girlfriend named Grace (Sophia Bush), who is in the car with him from the very first scene onward. When the time comes for The Hitcher to strap some sorry sonabitch in-between a truck and a trailer, he doesn't pick the girl.

Spoiler: it's splitsville for Jim and Grace.

Bad joke. Sorry. Point: Despite Grace's best efforts, Jim gets torn in half.

Karmic justice, I suppose. The horror film universe achieved its balance.

Back when the original Hitcher was still new, Harmon told Cinefantastique: "I don't think that anyone who sees the movie will be neutral about it. It's not really quite like other thrillers. I think audiences will be quite disturbed by this film." Today, I'm just disturbed by how unsurprising it is to see the girl die.

Where do you stand on The Hitcher 's infamous death scene? Do we give a bit of a "it was a different time" pass to older movies like this? Is that part of the charm? Or something we should view through newly enlightened eyes? Let me know in the comments.