As I promised, I finished the short story I was working on for the past month. This is the first completed full draft, and I’m sure I’ll be making many tweaks to it until it is published in my collection in the Fall. I’ve read so many books in my book club over the last few years that are set during World War II, and I’m presently watching some British movies about Winston Churchill, so I thought I’d try my hand at writing something from that time period. My son is looking at Lynchburg College, so I decided to set this one in Lynchburg since we have visited that part of Virginia for college visits.

As I promised, I finished the short story I was working on for the past month. This is the first completed full draft, and I’m sure I’ll be making many tweaks to it until it is published in my collection in the Fall. I’ve read so many books in my book club over the last few years that are set during World War II, and I’m presently watching some British movies about Winston Churchill, so I thought I’d try my hand at writing something from that time period. My son is looking at Lynchburg College, so I decided to set this one in Lynchburg since we have visited that part of Virginia for college visits.

I hope you enjoy it, and please feel free to leave me a comment or recommendation. I love getting feedback from readers, and since I am not presently in a writer’s group, I’d welcome any constructive criticism you may have.

Thanks an awful lot (as they would say in the 1940s).

Stephanie

Sophie’s Ladybug

The day her father left, Sophie cried. She stood at the end of the dirt path, her mother inside the house refusing to see him off, too resentful of what it was doing to her family to say goodbye. As the car destined for town that would have all the men board a bus that would take them to Fort Bragg arrived, her father gave a short wave and nod to her, and she waved back, fighting back the tears as hard as she could as he hoisted his sack into the vehicle and leaned inside. That’s when the tears began to flow. At twelve, Sophie was well aware of the dangers her father could face and the possibility that he may never return home safely. Plenty of her friends back home had lost their own fathers months earlier. Because of the stories she had heard and the sadness she had seen on the faces of people she knew well, she could understand her mother’s apprehension, worry, and desperation at the thought of being left to fend for herself and her child in this world.

The other end of the dirt path sat at the stone walkway to Sophie’s grandmother’s house, a grand white home with a sprawling front porch and wooden front steps perched in the lower mountains of Lynchburg. Her grandmother had taken them in while her father fought for the liberties of others. They had given up their own home four hours away up north, the one where they had lived for years, the one Sophie had called home, and the one where she had first believed in Lady Luck.

When her father had told her the news that he was headed to Fort Bragg, he relayed the news that Sophie and her mother would be moving and living with Grandma. They sat on their porch together back in Maryland, as he tried desperately to comfort her.

“It’s my duty,” he had said, trying to rationalize the idea of war and tighting to a young girl. “We have to protect what we believe is right.”

Sophie looked at him with her big blue eyes, her hair knotted from playing outside, her freckles more apparent because she was in the sun so often. She swallowed hard, knowing the decision was already made and there was no turning back.

As she reached to give her father a hug, a ladybug landed on Sophie’s shoulder, then another one on her thigh. Her dad looked at them and smiled.

“Well, Sophie-Belle, looks like you just brought us some luck. Those things are lucky, you know.”

“There are so many more this year,” Sophie said, looking at the small red and black beetle her dad had collected into the palm of his hand.

“Perhaps I won’t be gone for long after all,” her father said.

She remembered that day now, listening to the happy sounds of birds chirping in early spring, as she walked back up to the house remembering how she said goodbye to her father right here, the dirt flying off the tires of the car, as her dad disappeared down the road, off to protect his family in a different way.

She also remembered opening the door to the house and seeing her mother standing near the window staring straight ahead, a handkerchief in her hand. It was then that Sophie began to worry, and had subsequently remained worried for two full years.

*

Sophie played with Casper, her uncle’s dog, and ate brunch every Sunday on the wraparound porch of her grandmother’s house. They tried desperately not to pay too much attention to news from the war. They knew her father was in Europe—in France somewhere—and that things were not going as well as they had hoped. Only three letters had arrived so far. Her uncle, Timothy, would read the letters aloud as they would gather to hear her father’s words on paper. Timothy would not be joining the fight, as he had polio, walked with a severe limp—sometimes even with a cane—despite being only twenty-one years old himself. Polio did not discriminate, and although he had a positive outlook on life most of the time, Sophie had only seen him become bitter because of his fate once or twice. For the most part, he was cheerful and supportive. Timothy and her mother, although she was years older, had a strong bond. In the heat of the summer, her uncle would take her swimming, and they would all wade in the James River, and occasionally get a ride in friend’s rowboat, where she watched fish jump and attempted to catch something with a measly stick, string, and foul piece of a chicken wing. Sophie loved listening to the sounds of the crickets as she attempted to count stars while her uncle would play his guitar and her mother would sing, her lilting, soft voice echoing in the night air. At times, Sophie found herself listening to her mother’s voice as she sang, for it sounded hollow and melancholy.

Her grandmother did her best to keep them all from dwelling on what was happening in Europe. In fact, it was her grandmother who turned off the WLVA radio broadcast one night, they’d listen to report after report and become more depressed for doing so. It had become increasingly more difficult to listen to reports about the war and Hitler and lives lost. Her hands were poised on her hips, and she uttered the words, “No more.” They all looked at her standing there in her apron, her hair tied tightly in a bun on the top of her head, the lines on her face looking just a bit deeper than they did months ago.

“I have an idea,” she said.

She told Sophie, Timothy, and Sophie’s mother to all pile into the car and snatched the keys to her vehicle. The smell of autumn was in the air, despite that it was only September. The smell of the outdoors awakened Sophie’s senses. It was dusk, and her Grandmother put the keys into the ignition and began the drive down the roads lit only by the headlights and the early moonlight.

“Where are we going, Grandma?” Sophie asked, still unsure as to what her grandmother’s great idea might be.

“You will see soon,” she said.

After several minutes, Sophie could see buildings take form in front of her, and she knew they had reached downtown Lynchburg. What was going on this evening, she wondered. Where was her grandmother taking them at this hour?

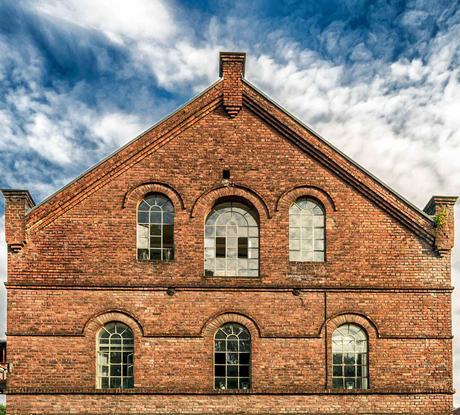

When they rounded the corner, Sophie could see a building rising up in front of them. Her grandmother—very much in control of her red Packard station wagon, a veritable renegade whom Sophie always admired for her positive attitude and spunk—pulled right in front of the Jones Memorial Library.

“We are going to the Library, Mother?” Sophie’s mother said aloud in an incredulous tone.

“We are.”

“But what on Earth for?”

“To take our minds off the news…the war. Let me show you what’s inside.”

Sophie’s grandmother had been working for many years at the library. She was one of three main librarians there.

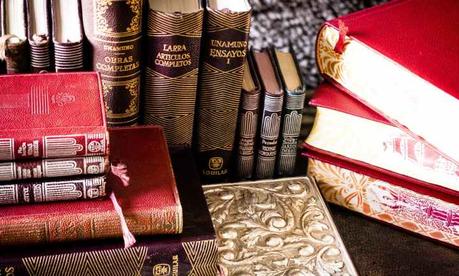

After struggling to get the key in the door as the library had been closed for a couple of hours, her grandmother finally gained entrance. Sophie loved the smell of the place—the smell of hardback covers and a mustiness that she couldn’t quite describe. Sophie’s grandmother turned on the dim lights, and the four of them stood in the middle and looked around. Libraries are typically a quiet place, but tonight, this one felt cathartic. There was something peaceful about it.

“Come to the back storage room,” her grandmother said, not in a whisper voice, but rather a regular talking voice. “I want to show you something.”

She opened the door to the storage room, Sophie right behind her, and they looked. There were hundreds of books scattered all over the place—on the floor, on the tables, and stacked up on chairs.

“What is all this?” Sophie asked.

“These are the books that we can no longer use,” her grandmother said. “They are either too old, falling apart, or we have so many extra copies we don’t know what to do with them. The head librarian gave us permission to get what we want first, and then we will have a little library sale and make a little extra money. So, as you can see, there are many. I will make a donation to the library, and we will have first choice, as I was approved to do so. I suggest we all pick three or four books to take home. I even cleared off a couple of shelves so we can have a begin to create our own home library. Or, we can just borrow from this library. But I want us reading and sharing—I’ve always wanted to do that. Does that sound like fun? Does it sound like something we could do to take our minds off the news reports?”

Sophie watched her mother intently, waiting to see her reply. Her mother was one to keep everything locked down deep inside and not share anything—not her feelings, her concerns, her worry, or her desire to be distracted by something. Sophie kept a keen eye on her to see how she would respond to her mother’s idea.

“I think it’s an ingenious idea, Mother,” Sophie’s mother said aloud to all of them. “I like it very much. I’d like to get lost in a good book and escape. And I’d like to get Sophie reading more.”

“Then it’s settled. If you want to purchase a few books, let’s do it. If you want to borrow some books, let’s do it. So here are the rules: we each pick three or four books we like to begin and that will make 12 books for our initial run at this thing. We can share what we are reading and how we like the books when we have dinner at night. Then, if we like the stories, we can exchange them and talk about them. But let’s sink our teeth into something other than these war stories that leave us depressed.”

And so they began to shuffle through the abundance of books in the back room. Sophie likened it to Christmas morning when they would open their presents, although there had been few gifts the last few years. Books made a wonderful companion to the long winter’s nights that would lay before them as the weather would soon be changing, and so Sophie plowed right in, searching for just the right ones to start off with on this new reading adventure. Sophie found a couple of Nancy Drew mysteries and The Hundred Dresses; her mother decided upon Dale Carnegie’s How to Stop Worrying and Start Living and A Tree Grows in Brooklyn; her grandmother scooped up The Portable Dorothy Parker and Agatha Christie’s Death Comes As The End; and her uncle spotted The Fountainhead and The Ministry of Fear.

Sophie could feel her spirits lifting as she perused the books. She liked reading, but she did not read enough, despite that her grandmother worked at the library. She was intrigued by the idea of reading and sharing; it gave her something to look forward to. Maybe she would read them all. She was turning into a young lady now, and perhaps she could attempt to read more sophisticated literature.

As they finished selecting their books, Sophie heard her mother say, “Do you think I could work here, too? Do they need any extra help?”

Sophie could not hear her grandmother’s reply, but she understood why her mother was asking. The library was certainly a place where one could get lost and forget all her problems.

They made their ride home in silence, each one of them pensive, thinking of their books, each one doing his or her best not to mention the word ‘war.’

*

When Sophie’s father’s letter finally arrived, it looked worn and beaten, as if it had been through a few tough passages itself. It was a Saturday morning, and the sun was rising high in the crisp November air. Sophie had read two books so far in addition to managing her own schoolwork and chores around the house. Her grandmother’s property needed a lot of upkeep, and with her grandmother working at the Library, in addition to her mother taking on a job at a factory in town, it was more important than ever for Sophie to do her part at home while others did their part elsewhere. And her uncle helped as he could, and had taken on the role of writing to soldiers as he could.

“Grandma,” Sophie said, as she ran into the kitchen, “it’s a letter from Dad.”

“Well, then you must open it and read it to me,” Grandma said, relieved that there was at least a letter in their hands.

Dearest Sophie, Addie, Mom, and Timothy,

I am writing to you from a small town in France, though I don’t think we’ll be here long enough for it to amount to anything firm and I’m not supposed to disclose our whereabouts. As you are probably getting reports from the radio, it’s not good here. We have lost a lot of men, and the fighting continues, although something inside of me is hopeful that it will not last much longer. I have heard the men talk of things happening, though I’m not sure when or where or how. Please know that I keep all of you in my heart and when I’m feeling particularly low or sad or overwhelmed by fear, I picture your faces in my head. I’m sorry that this is only the third letter you have received from me, but pen and paper are rare, and when we do find it, we all scribble things and try to get something sent back home because we know you are probably worried sick. It won’t be a long letter, but know that I love you all more than life itself, and that I will fight for us, and that I long to be home to see your smiling faces again. I will dream of hugging you all tightly,

Until then, much love,

John (or Dad)

Sophie sat and scratched her head as she looked out the window, her eyes becoming misty.

“He sounds so sad,” Sophie said.

“He just misses us tremendously,” her grandmother said.

“When he returns, we will have to lift his spirits and get him to join our reading club,” Sophie said.

“I think he’d like that very much,” Grandma said, as she turned her back to Sophie and sniffled. “He always was a good reader.”

*

Sophie’s mother stood in front of the crowd that had gathered inside the town’s library.

“Well, y’all, it’s the first Friday of the month, and I call this meeting to order,” her mother said, as she stood, trying to get the group that had assembled in order.

“As we have done for the last two months, we will take turns giving a two-minute overview of the book we have each read over the last few weeks. I hope everyone has finished their books.”

As word spread about Sophie’s family’s reading club, it had quickly grown to a group of twenty. People wanted to join. The library had offered to remain open late one evening every month, as the meeting was to begin promptly at 7 p.m. after the last factory shift had ended.

“Let’s start with you, Mrs. Bates,” Sophie’s mother said, and turned the program over to Mrs. Bates, who stood nervously, her book in her hand, and removed the kerchief from her head.

“Good evening, fellow readers,” Mrs. Bates said. “I’m here to tell you about the book I read, which I liked very much indeed and would recommend to you all. It is called Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier, and it’s about a woman who falls in love with a widower who owns a tremendous country estate called Manderlay, but his recent dead wife seems to haunt the place. And then there’s a woman, Mrs. Danvers, the housekeeper, who doesn’t much like the second wife and raised Rebecca and protects her memory. It’s a mystery, and I couldn’t stop reading it. And it’s set in Monte Carlo.” Sophie’s mother wrote the name of the book on the adjacent blackboard and gave it a check, which meant Mrs. Bates liked it.

When Mrs. Bates finished, everyone clapped. And that’s how it went for the better part of forty-five minutes as thirteen of the folks assembled shared what they were reading. Some were new members and this was their first time. Afterwards there was punch served, and Mrs. Conway brought her savory chocolate chip oatmeal cookies; Sophie talked with her friend, Beatrice, as the rest of the bunch mingled. Then, she and Beatrice began their hunt to gather information about the books they would put on their lists for their dads. Unfamiliar titles that men, perhaps, would like to read.

*

Sophie’s mother was wearing a powder blue dress with her work shoes and was off to her job the factory that day. Her face seemed brighter than it had been months ago. Working at the factory had helped her mood, that much Sophie could see. She had told Sophie that she needed “to help in any way she could” and it seemed to be making her feel better while they both waited for Sophie’s father to return. Her sense of humor had returned as well, and she said funny things to Sophie all the time.

It was May, and horrible, rainy, wet April was done. Sophie longed for the flowers to bloom and to feel the sunshine on her face, to wade in the river and to be done with school, and to stretch out on the grass on her favorite blanket and read a book.

Sophie’s mother kissed her on the forehead.

“Have a pleasant day today at school, and don’t let that boy pull your hair anymore, or I will have to speak to his mother.”

She winked at her daughter because she knew Johnny Doyle liked Sophie, which was why he was trying to get her attention. But Sophie wanted none of it. She was not interested in boys—well, at least not that one.

Her grandmother saw her off to school after her mother left. Johnny Doyle did pull her hair as they walked into the school, and Sophie kicked him in the shin. Johnny was shocked that she did this, his eyes opened wide in disbelief, and she stared at him, wondering if he would reciprocate. He did not. He simply walked away. She worried that he would tell the teacher she did this and she would get in trouble, but then she realized otherwise. He would not want to tell anyone that a girl kicked and hurt him. It would damage his pride. Truthfully, Sophie had had enough of it. This game of his had been going on for weeks.

At early recess, Sophie sat by herself under the tree in the schoolyard, and removed her latest book from her pile. She was thankful that reading kept her engrossed in other people’s stories and problems, so she could be less focused on her own. Less focused on missing her dad.

Within minutes, some cars started pulling up to the school and people were running toward it on foot. Principal Coates came running out of the school, which was an unusual sight, because Principal Coates was a bit rotund with a cherub face and Sophie had never seen him run before. His face looked more red than normal, and there was a smile that went from ear to ear. Sophie didn’t know what all the commotion was about, and then Principal Coates called the students into the main room, all of them gathered along with their teachers and the parents that had arrived.

“Children! There is great news today! Germany has surrendered, and the War in Europe is over. President Truman announced this today, but stated that we still have to win the war with Japan. It is halfway done!”

Sophie’s eyes filled with tears. Her first thoughts were of her father. Would he be coming home soon? Then, she thought of her mother. She couldn’t wait to see her her—to find out what she knew. But Germany had surrendered! She was so happy. She was so happy to hear some good news. She hugged Beatrice. Everyone. All around her, people hugged and celebrated. She didn’t know quite what it all meant or what the details would be, but she could tell from seeing the hugging and joy that this was fantastic news.

Johnny Doyle did not pull her hair on the walk home. In fact, he stayed ten steps behind her and didn’t come anywhere near her. His retreating made her feel a little badly about what she had done to him. He wasn’t so bad, really. She knew she shouldn’t have kicked him, and she probably shouldn’t have kicked him as hard as she did.

As they got near the forked road where Sophie’s house was down the road to the left and Johnny’s house was down the road to the right, she turned around to face him and stopped.

“Hey, Johnny,” she began, timidly, “I shouldn’t have kicked you. I’m sorry I did that.”

His face brightened and he looked at her. He knew he needed to be a man and apologize as well.

“I’m sorry I pulled your pigtails. I shouldn’t do that. Sorry.”

Sophie stuck out her hand to him. She was so happy about the news about Germany that she wanted to shake Johnny’s hand a make up. This was no time to be at war with anyone. Even a boy who constantly pulled your pigtails.

“Friends?” she asked.

“Friends,” he said, placing his hand in hers for the handshake. “So you think your dad will be home soon?”

“I think so,” she said. “At least that’s what I’m hoping for.”

When she opened the door to the house, she hear loud music playing from the radio and saw her grandmother was dancing around the kitchen. Sophie smiled when their eyes met, and she knew that she knew.

“You heard the wonderful news, Sophie?” her grandmother asked, approaching her to give her a big, smothering hug, kissing her on the top of her head.

“Yes.”

“We are going to town to celebrate. Everyone’s celebrating. Your mother must be beside herself by now.”

Sophie’s face hurt from smiling, as her grin felt permanently plastered and stretched across her petite, freckled face.

*

The celebration outside the factory lasted for hours and hours. People hugged and cried and laughed. Music played. They guessed when their loved ones would come home.

Sophie had never seen so much hope and love in one place.

She sat on the grass with Beatrice and watched the celebration.

“Oh,” Beatrice said, “there’s a ladybug on your shoulder. Want me to get it?”

Sophie stopped Beatrice from reaching for it.

“I’ll get it,” she said, and gingerly held the Ladybug in the palm of her hand.