The Panic of 1873 and subsequent Long Depression in the U.S. began on September 18th with the failure of Jay Cooke and Co., although signs of distress had already apparent in the market. The day came to be known as Black Thursday, but this moniker has since become more familiar as a reference to the Great Crash of 1929. With the effects of the Great Recession of 2008/09 still apparent in the economy, the study of financial panics and resulting downturns has taken on new importance. As more is learned about the recent financial problems it has become apparent that past historical crises had many of the same characteristics. The Panic of 1873 illustrates many of the same patterns as other financial crises, including the last one. Novel innovations created unique changes in the economy and this affected the psychology of the investing public. Optimism became mania, inevitably turning into panic and discredit, and the end result was a long lasting liquidation in the economy. A look back to 1873 also presents a chance to illustrate that government involvement has long been a traditional factor in the American economy, as have the specters of corruption and fraud. While understanding economic crises is important, a look back at the railroads and the construction of the Northern Pacific will also highlight America’s legacy of growth through collective effort.

The Railroads

In 1828 the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O;) was the first railroad in the U.S. to be chartered (Atack, Passell 427) and by 1860 there was already 30,626 miles of track in place. To put this in perspective, the peak in canals occurred in 1850, when a much less significant 3,698 miles of manmade water ways were in use, with some of those passages unusable during icy winter conditions. By the turn of the century the US had crisscrossed its railroad tracks over the full width of the continent, utilizing 193,246 miles of track. This was more than the whole world combined (Klein 62). In the ten years between 1865 and 1875 the US saw the addition of 30,000 new miles of railroad track, which, for a cost of close to $2 billion, was almost double the amount of existing mileage at that time. There was an expectation at the time that expanding railroad track was a good investment because it would result in rapid economic development of new regions and trigger the appreciation of prices for land. A real estate advertisement from the time promoting land in Columbus, NE makes the pitch that “[A] $50 lot may prove a $5,000 investment…” (Chancellor 183). With the Transcontinental Railroad, born of the combined efforts of the construction of the Central Pacific east from San Francisco and Union Pacific west from St. Louis leading the way, the industry experienced unprecedented growth after the Civil War, with a peak in 1871. There was $2 billion invested in railroad expansion between 1867 and 1873 (Schumpeter 335). This demonstrates that the anticipation of massive returns was part of the zeitgeist around the American railroads and western expansion.

Complexity economist W. Brian Arthur has used the railroads as an example of how technology domains evolve. Bodies of related technology emerge organically over decades and are often triggered by a novel invention that captures the effects of a natural phenomenon in a way that was previously unimagined. A technology domain is not one single invention though, but a process of innovation that adapts the whole economy to it. For example, the Digital Domain that began in the 1940s is currently still evolving with the work of countless engineers and programmers, and the technologies that have emerged have redomained the entire world economy around computerization (Arthur 145). The technological revolution surrounding the railroads had the direct effect of lowering transportation costs, but it also dramatically transformed other parts of the economy as well. Iron production increased from 38,000 tons in 1850 to 180,000 tons in 1860 and this new demand drove innovations in technology for mass production of iron and other industrial materials (Arthur 152). Walt Rostow has credited the railroads with America’s launch into economic self sufficiency by greatly widening the national market, spurring development of our export sector which became an engine of capital generation, and besides the iron industry it created the modern coal and engineering industries (Atack, Passell 428). The Railroad Domain forever changed the face of commerce in America just as the country is currently transforming with the rise of the Digital Domain.

The prolific construction of railroads and telegraph lines, as well as the growth it spurred in industrial mass production in the second half of the 19th Century, required innovative ways of raising large amounts of needed capital. The entrepreneurial and financing function of railroad construction started with promoters obtaining rights of way, then chartering a company and securing lucrative government land grants. Bonds were marketed and sold to obtain construction funds and equipment and were purchased on installment plans with equipment trust certificates (Schumpeter 335). Commercial paper was introduced so that corporations on sound financial footing could borrow from short term markets with less expense than obtaining bank loans. Preferred stock was a primary source of railroad financing from 1843 to 1850, and other financial innovations that developed from the rapid industrialization of the time were convertible bonds, warrants, and bond covenants (Allen, Yago 60). By the early 1870s railroad financing had reached a highly leveraged and extremely precarious position (Atack, Passell 431). As in other financial crises, the time preceding the crash in 1873 was characterized by an over extension of credit that could not be sustained when the rapid growth of the era slowed down.

The financing needs of the railroads were also subsidized by the federal government. The precedent for federal involvement in transportation projects originates from legislation in 1802 that allocated 5% of the receipts from government land sales to finance public road construction (Atack, Passell 435). The government assisted the railroads, especially the transcontinental ones, with massive land grants. This allowed the railroads to finance construction from the proceeds of preferential real estate deals. The mortgage market was more developed than bond and equity markets at this time, so land grants were a useful way to obtain capital when returns from actual operation were years away. Between 1851 and 1871 the railroads received 131 million acres in free land (Atack, Passell 436). The justification for this massive government involvement in the economy was the social benefit that increased commerce would bring to the entire nation. For the Union Pacific alone the private return on investment was 11.6% while the social return was 29.9%, on average, in the years 1870 to 1879 (Atack, Passell 435). Other benefits, that are harder to measure, accrued to the public, such as rapid postage delivery and the increase in national security with the ability to transport large numbers of troops and cargo from one side of the continent to the other.

The railroads and other innovations of the second industrial revolution, such as the telegraph, fueled the excitement of speculation, and the “error and misconduct accumulated” (Schumpeter 333). Without political and financial encouragement this upswing in production would not have happened. Technology domain revolutions can have the effect of over-stimulating the economy, with bubble creation (Arthur 149) when the new technology of the age builds optimism in the public to the point where new era thinking predominates. The dot-com bust and boom of the 1990s is a great example of how new technologies can encourage this “irrational exuberance” (Stiglitz 10). Railroad stocks peaked in 1869, remained flat during the economic boom in 1871, and then began sliding in 1872 when investment capital bid up other industrial stocks. Railroad financing was impacted negatively by tight money, low bank reserves, and a slight market panic in October 1871, through the mechanism of slower export growth and increased imports (Schumpeter 336-337). Railroads and the industries built by this new technology domain became objects of speculation that took the economy to unprecedented heights, but made the likelihood of the crash that much greater.

An International Economic Storm

Economic growth and financial speculation grew quickly in Europe as well in the early part of the 1870s. The end of the Franco-Prussian war created an indemnity owed by France, from which 1/10 was supposed to be paid in gold, fueling speculation in Germany and Austria (Kindleberger 137). A building boom spread across Europe from 1869 until 1873 which pushed up wages while wholesale prices fell, suggesting a boost in actual production. The productivity gains and rapid growth instigated speculative investment (Schumpeter 336). Other shocks to the economic equilibrium of the time also came from the 1869 opening on the Suez Canal, the inflation caused by Germany’s addition of new coins to the money supply, without withdrawing silver from circulation first, the 1871 Chicago Fire, and Otto Von Bismarck’s unification of Germany into one country (Kindleberger 137). All of these events acted as shocks to the equilibrium of the world economic system.

The Panic of 1873 and resulting downturn was the first truly international economic crisis in history, with the crash in markets originating in Austria and German in May, moving to Italy, Holland, Belgium, and the US in September, and then England, France, and Russia after that. Baron Carl Meyer von Rothschild described this new era aptly: “the whole world has become as city” (Kindleberger 137). The panic was transferred to the US from Germany and Austria when the crash there stopped the movement of money across the Atlantic for speculation in railroads and western lands (Schumpeter 336). There was already an infrastructure in place for obtaining investment funds for America in England and Europe (Schumpeter 335), and Jay Cooke marketed Northern Pacific (NP) bonds heavily in German speaking Europe. For public relations purposes he even renamed the site of NPs terminal on the eastern side of Missouri River Bismarck, in honor of the Prussian leader, and this eventually became the capital of North Dakota (Lubetkin 120). The building boom in Austria and Germany also prevented Cooke for raising money in Frankfurt (Kindleberger 137). These global economic woes set the stage for a historic crisis.

Jay Cooke & Co. and the Northern Pacific Railroad

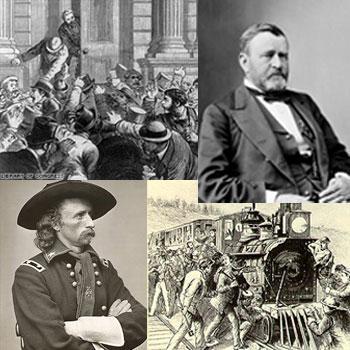

The legendary financier Jay Cooke built his reputation and fortune by acquiring $1.6 billion in financing for the Union during the Civil War (Lubetkin 3). The financial markets in New York gained national prominence at this time as money was funneled through the city’s brokerages (Allen, Yago 60). Cooke’s innovative strategy of marketing war bonds to the emerging middle-class of farmers, merchants, and artisans using patriotism and the abolition of slavery as selling points made him a multi-millionaire (Lubetkin 8). Jay Cooke viewed himself as “God’s chosen instrument” (Lubetkin 13), and when the newly elected President Ulysses S. Grant passed him over for appointment as Treasury Secretary he was disappointed, but soon directed his attention to building a second transcontinental across the northwest (Lubetkin 15). Cooke became the financier for the Northern Pacific Railroad (NP) in 1869 after getting assurances from the corporation’s officers that the costs of constructing track from Lake Superior to Puget Sound were projected to be slightly more than $85 million (Lubetkin 24). Unfortunately for Cooke, his inability to cover $15 million worth of outstanding NP bonds on September 18th, 1873 resulted in the permanent closing of all three of the reputed Jay Cooke & Co bank branches.

The failure of Jay Cooke and Co. was not simply an issue in over-speculation in railroads, and the story of the fall of America’s most prestigious financier calls for a deeper look. Rival financier and railroad titan Cornelius Vanderbilt’s assessment was quoted just hours after the crash: “Building railroads from nowhere to nowhere at public expense is not a legitimate undertaking.” (Lubetkin 287) However, despite the crisis, the NP never actually failed and with 7.8 million acres of new track certified in Dakota and Oregon by the end of 1873 it was able to stay financially solvent by trading land for bonds (Lubetkin 286). The NP had positive cash flow, the immigration into the northwest regions it serviced continued to grow rapidly, and traffic was increasing geometrically (Lubetkin 288). Without fresh financing, construction on the line was halted until 1879. The last spike was eventually driven into the ground in 1883 to complete this second transcontinental railroad. The NP remained in operation for almost a century, but in 1970 it was consolidated with its competitor, The Great Northern Railroad, into the Burlington Northern system (Lubetkin 286). Considerable failures mounted for railroads all over the country after 1873, but with the NP remaining solvent, the failure of premiere Jay Cooke & Co. is a bit more perplexing.

It had not even been Jay Cooke’s idea to close his banks on September 18th, but rather that of the operating manager of his New York branch, Harris Fahnestock. On that fateful morning Fahnestock called three powerful New York bankers to the offices of Jay Cooke & Co., including John Thompson, founder of the First National Bank. It was claimed that if securities of $1 million could not be pledged by 10 o’clock then the bank would shut its doors. No securities could be provided and Fahnestock, along with Jay Cooke’s other partners Francis French and James Garland, physically ushered customers out of the bank and locked the doors. The panic hit Wall Street within fifteen minutes, as Fahnestock personally brought the news to the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) to be read aloud by the clerk per the custom of the time (Lubetkin 280). Fahnestock, French, and Garland had entered secret negotiations with John Thompson of First National Bank with the help of their friend George F. Baker to become partners with Thompson. They all found jobs at First National Bank in 1874, but it did not become known that they were partnered owners until 1877 (Lubetkin 281). Jay Cooke, who was hosting President Grant at his mansion Ogontz in Pennsylvania on morning of September 18th, 1873, was not consulted by Fahnestock about the closures, and received the news after the fact by telegram. It was too late by the time he rushed to his Philadelphia branch, and along with his Washington D.C. branch, it experiences a run and had to close as well. Jay Cooke eventually broke down into tears when the realization that he was completely bankrupt set in (Lubetkin 282). Some of what happened on that day had the hints of a coup d’état.

Cooke’s partners, including his brother-in-law, William Moorhead, whose poor performance running the NP’s subsidiary railroad the St. Paul & Pacific resulted in miles of unneeded track and wasted resources, had lost confidence in Cooke and his faith in the NP. (Lubetkin 287-288). The NP’s decision to begin construction on new track from Bismarck to Yellowstone was seen as a betrayal by Fahnestock after Cooke had promised a moratorium until Jay Cooke & Co. was in a better financial position. Besides the suspicion of an inside job, the failure of Jay Cooke & Co. was a chaotic conflagration of circumstances. He had other powerful business interests opposed to and working actively against him, including J.P. Morgan and the British Government, who conspired to prevent Cooke from receiving financing in London due to fears that competition from the NP would hurt Canada’s railroads (Lubetkin 287). Another problem facing the bank was a loss of patronage from Grant when the President blocked the sale of federal bonds in 1872 and ended Cooke’s Civil War era monopoly on their sale in 1873, leading to the loss of a key source of revenue (Lubetkin 287).

The lack of political patronage was possibly related to the Credit Mobilier scandal of 1869, for which revelations continued to hit the press. Credit Mobilier of America was a construction shell company set up by the owners of the Union Pacific Railroad in order to shorten the time frame before returns could be earned. This worked by funneling construction purchases through Credit Mobilier as an intermediary with an abnormal margin skimmed off of the top. Massachusetts Congressman Oakes Ames was implicated in a scheme to keep legislation from ending the fraud by distributing Credit Mobilier stock to key players in Congress at bargain prices. The scandal reduced public confidence for investing in railroad bonds and created an impetus for President Grant and Congress to forego further government help for the NP (Lubetkin 21, 287).

By and far the most dramatic factor affecting Jay Cooke’s financing of the NP was the ferocity by which Sitting Bull and the Sioux Nation were willing to start a war with the US in order to prevent the encroachment of the railroad onto their great plains, because they believed the result would be the end of their way of life. Although rarely mentioned in the context of the Panic of 1873, the effect that press stories should not be underestimated, with reports of Indian war parties clashing with the army soldiers led by Colonel David Stanley and the famous Colonel George Armstrong Custer, as they bravely defended the NP surveyors from certain death. Custer, besides being a cavalier military commander, moonlighted as a journalist, and penned slightly embellished accounts of two battles against the Sioux on August 4th and 11th, in which he paints a dire scenario that was only saved by his superior leadership. These accounts appeared in the September 6th addition of the New York Tribune (Lubetkin 273) and likely did more to undermine confidence in Jay Cooke & Co. than any other news that month. The NP was trying to build a railroad through a “war zone”, and this image hurt bond sales and financing (Lubetkin 290). The failure of Jay Cooke & Co. would result in a wholesale loss of confidence everywhere and in everything though.

The Panic

After Jay Cooke & Co. closed its doors on Wall Street the panic spread immediately. Land and stock speculation disintegrated, prices fell precipitously, and a large number of firms failed right away (Schumpeter 337). Daily margin call rates rose to 5% as trust evaporated in the ability of all creditors to make good on loans (Chancellor 184). A report from the day describes the chaos, “The brokers surged out of the Exchange, tumbling pell-mell over each other in the general confusion, and reached their respective offices in race-horse time. The members of firms who were surprised by this announcement had no time to deliberate. The bear clique was already selling the market down in the Exchange, and prices were declining frightfully.” (“The Panic of 1873”) The famous robber baron Cornelius Vanderbilt drove his carriage down Broad Street directly into the throngs of people in order to physically disperse the panic. The collapse resulted in the New York Stock Exchange closing its doors for the next ten days in an unprecedented attempt to allow calm to reassert itself in the markets (Chancellor 184).

There was a run on deposits on Black Thursday that lasted three days with most of the runs happening to the country banks. No security could be cashed in or redeemed. The panic spread across the country and bank runs led to the closure or suspension of 101 banks. New York experienced 37 failures, Philadelphia had 22, and banks closed in Virginia, Washington D.C., Illinois, Ohio, Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Michigan. Most of the banks that went under were private brokerage houses, but national, state, and savings banks were also caught in the crossfire (Wicker 18-19). The Secretary of the Treasury, Salmon P. Chase, bought $13.5 million in National 5-20 bonds, but this tepid government response did little to calm the markets (Juglar 95). Although there was no Federal Reserve at the time in order to act as lender of last resort, the New York Clearing House (NYCH) filled this role. From 1860 until 1873 the head of the NYCH was the powerful George S. Coe, who was also President of the Exchange Bank. The NYCH had two tools at its disposal for combating banking panics and liquidity crises, in the form of loan certificates and reserve pooling. The pooling created central banking power for the NYCH, and was in fact bigger and possessed more clout than any of the official European Central Banks at the time (Wicker 16). The clearing house also took the extreme step of suspending direct cash payments on September 24th, while maintaining a cash lifeline to the interior banks (Wicker 31). The amount of bank failures and resulting risk aversion likely helped prolong the economic depression that was to follow.

The Long Depression

Using economic data for railroad operating revenue, the value of total marginal imports, selected cities, as well as pig iron, and cotton and coal production, it has been estimated that the average percentage decline in overall production was 33% between 1873 and 1878. To put this in perspective, the same areas of production showed a 56% decline between 1929 and 1932, indicating that the Great Depression (GD) was substantially worse in terms of the depths to which production fell when it hit bottom, even if the Long Depression (LD) had greater duration in terms of years in decline (Scott 574). Comparisons of copper consumption show that the recovery in this key indicator took longer for the GD than the LD, with a full recovery taking 11 years for the former versus 7 years for the latter. Between 1873 and 1876 copper consumption dropped from 42.8 to 26.7 million pounds, but by 1880 the rebound had reached 65.3 million pounds. Between 1929 and 1932 the fall in copper use was more dramatic with a decline from 1,778.6 to 519.2 million pounds, with a full recovery not being reached until 1940 at 2,017.6 million pounds (Scott 576). Other calculations of total Gross National Product during the period between 1869 and 1875 show that gross production measured in real terms shows no decline, but in fact at 29% increase, with growth only stalling between 1873 and 1874 (Wicker 30). These data suggest that the LD was a shallower and shorter downturn that the GD.

Wholesale prices fell 30% during the LD, although the decline began in 1865 and did not fall below pre-Civil War levels until 1878 (“Effects of Price” 608). Appreciation of the dollar’s spending power was boosted by legislation in 1875 that brought the U.S. onto the Gold Standard by 1879 (“Effects of Price” 608). The railroads competed aggressively for traffic by slashing prices and a rate war broke out from 1870 to 1893. Attempts at collusion in the industry in order to lift profits were ineffective, leading to the more common strategy of undercutting competition in order to acquire them (Klein 72). The crisis in 1873 exacerbated this behavior when many railroads went into receivership, became acquisition targets, and with their debt no longer holding them back they cut prices even further (Klein 71). More price wars between the railroads in 1877, along with general deflation, caused profits to fall, kept investors away, and prolonged the contraction for longer than would have been the case in an inflationary environment (“Effects of Price” 606).

Joseph Schumpeter (337) argues that even though prices in the 1870s did not fall as abruptly as they did in the 1930s, the social and political problems that resulted were equivalent in their severity. There were granger movements, demands for inflation, strikes, riots, and the he characterizes the period between 1874 and 1878 as “unrelieved gloom” (Schumpeter 337). The Molly Maguires instigated labor violence and acts of terrorism in the Pennsylvania coalfields. The agitation of labor also resulted in the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 in Pittsburg. Religious revivalism gained ground, with evangelist Dwight D. Moody and gospel singer Ira Sankey drawing huge and repentant crowds in New York, drawn from the residents and workers around Wall Street and Fifth Avenue (Chancellor 186). Accurate unemployment numbers are hard to estimate for the 1870s, but Schumpeter (337) speculates that it could have been higher than in the GD based on reports from the winter of 1873-1874 that there were estimates of 3 million tramps searching for work. Large job losses happened so quickly that the unemployed were rioting in New York as early as January 1874. By 1877 it is estimated that only 20% of the potential labor force had actual steady employment (Chancellor 186), suggesting persistent underutilization. Other estimates of unemployment for the period extrapolate from the 28,500 jobless in Massachusetts to a national total between 318,000 and 570,000, indicating a much less dire view than Schumpeter’s (Wicker 31).

Railroad profits declined in 1875, but a slight reversal in 1876 saw new construction of track, and purchases of locomotives. However, another round of failures and stock declines hit the railroads in 1877 (Schumpeter 338). Traffic and revenues rebounded completely in 1878 signaling the end of the slump. Schumpeter (338) suggests that the objective indicators of fundamental economic growth appeared before the improvement of surface indicators, including the public’s expectations. This indicates that the rebound in production happened naturally, even while prices were still generally falling. American shipping accounted for 19% of the world’s total in 1860 at 2.5 million tons, but by 1870 the share was down to 9% and by 1880 it was only 7%. America did not recover its trading position relative to the rest of the world until World War I (“Vicissitudes of the Shipping Trade” 608). Charter rates declined between 1874 and 1879, and there was a 70% reduction in the price of rice shipped from Burma to England (“Vicissitudes of the Shipping Trade” 607).

A major factor in the extended nature of downturn after the Panic of 1873 was the Coinage Act of that year, referred to as the “Crime of ‘73” by its opponents. The act took America off of the bimetallic standard of silver and gold, and gold became the only source of backing for the currency. This had the effect of constricting the money supply and restricting the availability of capital for continued business growth. The resulting deflation benefited banks, but at the expense of farmers who had to pay back loans in money that was more valuable than when they borrowed it while the return for their agricultural products declined with the price. When President Grant gave his State of the Union speech in December of 1873 he reflected on the economic problems, but pointed to his tight monetary policy was the best way to prevent the even worse scourge of inflation (“Panic of 1873”). Deflation, widespread persistent unemployment, and sluggish economic activity were a hallmark on the decade during the Long Depression, and government policy of restricting the money supply was a substantial factor.

Conclusion

The Panic of 1873 and Long Depression present a study of an economic downturn that in many ways is similar to the Panics of 1929 and 2008, and the resulting Great Depression and Great Recession. The Long Depression and Great Depression were each the worst downturns of their respective centuries, and although it has a way to go the Great Recession will be the downturn to beat in the 21st century. Speculative fever fueled the booms prior to each economic collapse and each resulted in an abnormally prolonged slump. Over leveraging in the financial sector resulted in a dramatic unwinding of debt and trust in banks and institutions collapsed instantly. The need for someone to fill the role for some sort of lender of last resort is supported in each case, as well as the need for a flexible monetary policy.

The debate over whether government involvement in the economy is a hot topic right now, and despite the clear cases of market and business failures in recent years, small government advocates are gaining clout. The economic history of the U.S. prior to the New Deal is often mythologized by the political right wing as a free market paradise. After closer inspection of the country’s economic growth in the 1800s it becomes apparent that government policy was instrumental in this process. Whether the land grants to railroads, legislation on silver coinage, or the Army’s veritable declaration of war against the Sioux Nation on behalf of Jay Cooke and the Northern Pacific Railroad, the government has been involved in economic decisions for better or worse for a long time. The railroads, just like the internet more than a century later, had government intervention as an instrumental component of their establishment. These benefits are still being felt today.

Jared Roy Endicott

Works Cited

Atack, Jeremy, and Peter Passell. A New Economic View of American History. Second Edition. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1994. Print.

Chancellor, Edward. Devil Take the Hindmost: A History of Financial Speculation. New York: Plume, 1999. Print.

Juglar, Clement; Decourcey W. Thom, Ed.. A Brief History of Panics in the United States.New York: Cosimo Classics, 2006 (orig 1916). Print

Kindleberger, Charles P., and Robert Aliber. Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises. Fifth Edition. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2005. Print.

Klein, Maury. The Genesis of Industrial America, 1870-1920. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007. Print.

Lubetkin, M. John. Jay Cooke’s Gamble: The Northern Pacific Railroad, the Sioux, and the Panic of 1873. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006. Print.

Schumpeter, Joseph Alois. Business Cycles: A Theoretical, Historical, and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process, Volume I. First Edition. Chevy Chase, MD and Mansfield Centre, CT: Bartleby’s Books & Martino Publishing, 2005 (orig. 1939). Print.

Wicker, Elmus. Banking Panics of the Gilded Age. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000. Print.

“The Panic of 1873.” The History Box. Web. 30 May. 2010.

Academic Journal Articles

Davis, Joseph H.. “An Annual Index of U.S. Industrial Production, 1790-1915.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 119(4) (Nov. 2004): 1117-1215. EBSCO. Web. 29 Apr. 2010.

Decker, Christopher S., and David T. Flynn. “The Railroad’s Impact on Land Values in the Upper Great Plains at the Closing of the Frontier.” Historical Methods 40(1) (Winter 2007): 28-38. EBSCO. Web. 29 Apr. 2010

Fackler, James, S., and Randall E. Parker. “Anticipated Money, Unanticipated Money, and Output: 1873-1930.” Economic Inquiry 28(4) (Oct. 1990): 774-787. EBSCO. Web. 29 Apr. 2010.

Fels, Rendig. “The Effects of Price and Wage Flexibility on Cyclical Contraction.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 64(4) (Nov. 1950): 596-640. EBSCO. Web. 29 Apr. 2010.

Gregg, E.S.. “Notes and Memoranda: Vicissitudes in the Shipping Trade, 1870-1920.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 35(4) (Aug. 1921): 603-617. EBSCO. Web. 29 Apr. 2010.

Scott, Ira O., Jr.. “A Comparison of Production during the Depressions of 1873 and 1929.” American Economic Review 42(4) (Sep. 1952): 569-576. EBSCO. Web. 29 Apr. 2010.