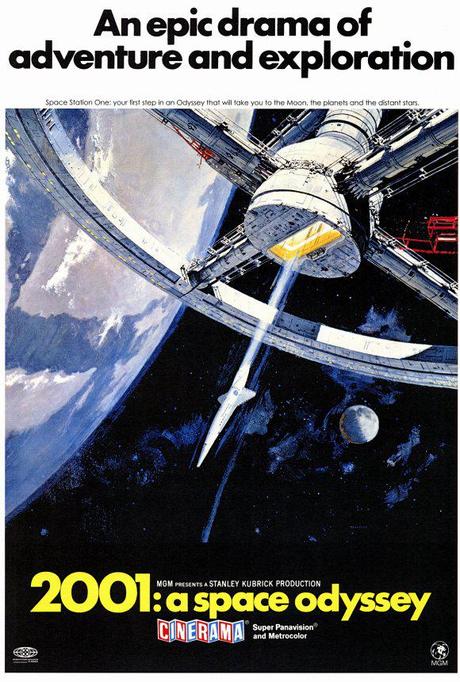

Welcome to the All-Time Favourites Series. This series examines 25 of the greatest films I’ve ever seen, looking at them in depth with analyses of what makes them great, and cutting down to the most basic level, looking at plot, cinematography, writing, direction, acting and other things, to see what makes these great films tick. For more on the series, click here. This week’s film is 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Epic. It’s a word that’s been used to describe a lot of films. I’ve used it many times. What do we define it as? In a film lover’s vocabulary, the movie that’s likely to spring to mind is Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey. Not only is it grand in size and scale, it’s also incredibly influential, and easily beats any of David Lean’s epics any day of the week.

One of the earliest films to examine America’s journey into space, this might not be the most informative of the bunch (that title belongs to 1985′s The Right Stuff), but it is certainly the most rigorous, adventurous and astonishingly well-made. Kubrick, who had a 40-year career that resulted in twelve films, was never better than here. This is him at his most concentrated, and amazing. 2001 is not only his best film, but also one of the best of all time, up there with such masterpieces as The Battleship Potemkin, Citizen Kane, 8 1/2 and The Godfather.

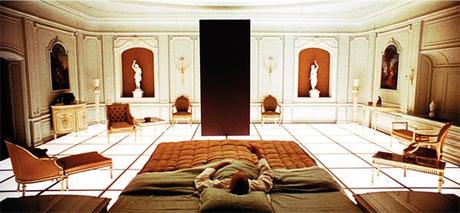

It is easily one of the most visually amazing movies ever made. It’s opening shot is one of stunning beauty: the camera rises up behind the moon to see the sun in the background forming a crescent of light on the Earth and plunging the rest of it into darkness, as the tune that defines epicness, Also Sprach Zarathustra, plays blaring on the soundtrack. From here we journey to ‘The Dawn of Man’ and see the early apes, who lived thousands of years ago. Their idyllic civilization is disrupted by the sudden presence of a black monolith, or obelisk, which is so mysterious and questionable that when we see it on screen we are instinctively chilled. It’s meaning is beyond our understanding, as is where it came from. Cut to the future… the year 2001, and astronauts have discovered a monolith that looks exactly the same on the moon, sending a radio signal to Jupiter. So they send two astronauts to investigate, but the computer HAL onboard the ship in which they’re traveling becomes infected and attempts to stop them from what it sees as a sabotage. “This mission is too important for me to allow you to jeopardise it,” he says, and Kubrick hints that HAL’s motives for trying to kill the astronauts are beyond our understanding. Could the “aliens,” or whoever created the monoliths, be controlling the computers of the world too? I couldn’t help but wonder what was happening back on Earth; if they were growing in their control of the universe. But I didn’t dwell on the thought, and Kubrick doesn’t either.

His film deals, on the primary level, with the idea of our place in the universe. It’s a question too bold to answer; I believe there is no answer, but Kubrick attempts to discover more about the endlessness of space and how, in all that darkness, the answers to so many questions must lie. The monoliths exist, as many have spoken, to help move those in its presence to the next evolutionary stage. When the apes touch it, it somehow teaches them, gives them knowledge… and makes them more volatile. It’s effects are impossible to comprehend. When astronauts stand next to it on the moon, they are stunned in a state of complete awe. Does it hold the answers, or is it simply infecting us with new questions? Who knows. Kubrick doesn’t, and we certainly don’t, but it doesn’t stop us from wondering.

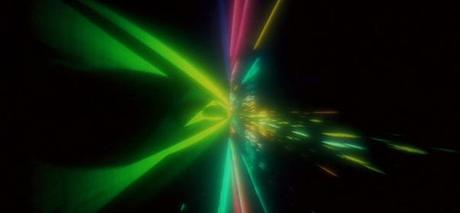

The screenplay, based on a novel by Arthur C. Clarke and adapted by Kubrick, is superb. The film contains little dialogue, but what is said is perfect. There is also even a sense of humor. Though the film is contemplating bigger questions on an existential level, Kubrick does take some time to delight in imagining what the little things of the future would look like, such as zero gravity toilets and video phone calls. The cinematography and direction by Kubrick are also stellar; perhaps the true star of the film. There are countless stunning shots, from the aforementioned opening scene, to the famous jump-cut to the future from the ape world, to the slow motion space ballad; the haunting red eye of HAL to the shot of a small space pod being dauntingly confronted by the giant ship it came from; the everlasting and incomprehensibly meaningful stargate sequence, to one of the last shots of the film, in which the camera “enters” the monolith. All these images and more are part of the indescribable beauty of the master’s revolutionary sci-fi masterpiece. It is certainly a film reliant on images rather than dialogue; what else can you call a movie whose last lines are spoken forty minutes before its conclusion?

Kubrick’s film is definitely one that will leave you startled and confused. The beautiful but enigmatic ending has left many annoyed and frustrated, but when I first saw it I thought it was perfect. I still think it is perfect. A lot of people don’t understand it, and refuse to think about it. I’ve seen the film many times, and I think I understand everything. The film epitomises the term thought-provoking to an incredible level. I’ve never seen a film that has made me think on such a huge level as this. It raises questions of daunting proportions, and cheekily refuses to answer them. It leaves the answers up to us, as individual audience members: previously idiotic questions like “Why are we here?” become scarily relevant. If we can’t comprehend an answer, at least we are thinking about it. Never has a film and never will a film provoke such large questions; this is a film that, whether we are watching in a cinema or at home, will leave more of an impression on us than any other cinematic advent.

–

That’s this week’s All-Time Favourites review. What do you think of the film? Leave a comment below, and look out for next week’s post, which will be looking at The 400 Blows.