After climbing a great hill, one only finds that there are many more hills to climb.

– Nelson Mandela

I felt it in my stomach, powerful and resonant, its sonic boom awakening the pre-race butterflies like a sudden gust of wind.

I felt it on my skin, the chill of goosebumps cascading like dominos along my arms and down the back of my neck.

I felt it in my head, the last vestiges of denial evaporating like sweat in the pre-dawn darkness. This is happening.

Nothing drives home the reality of Comrades like “Shosholoza”.

I’d heard South Africa’s “second national anthem” before. Watched start line videos like my own below, trying to appreciate how the Ndebele mining song’s vocal harmonies would sound—and feel—on race day. And honestly, I thought I’d prepared myself for the moment.

I thought wrong. “Shosholoza” hit me like the oncoming steam train whose sound it evokes. I held my iPhone aloft, capturing the surreal scene, a panoply of emotions dancing across the 17,000 faces lost in their last-second thoughts or softly singing along. The air in the start corral strained under a pungent mix of body odor and human electricity, the latter more than enough if called upon to power the harsh floodlights illuminating the start line.

Despite the cool morning, I was sweating—unusual for me, but then again I’d started sweating the moment I’d woken up around 2:00am, pulse rate elevated and nerves firing like I’d taken a shot of adrenaline straight to the heart, Pulp Fiction-style. I’d started chugging water immediately to try to counteract my body’s overactive sweat glands. There are few ideas worse than crossing the start line at Comrades already dehydrated.

The sea of faces was much darker and more masculine than I was accustomed to from American races—not surprising for a South African race with over 93% African representation. (Fun fact: Ethiopia, home to many of the world’s elite distance runners, sent only one runner to this year’s race). This was my first time in Africa, and I couldn’t imagine a better way to christen my 4th continent than by accepting the challenge of the Ultimate Human Race.

All of us stood in quiet deference as “Shosholoza” expanded to fill the silence around City Hall. All 17,031 of us, citizens of 73 nations speaking who-knows-how-many languages. All of us united in our common goal and in our common desire to see one another achieve that goal.

All of us Comrades.

Start-line perspective from the VIP seats: that’s Rory front & center with glasses

Case in point, a simple but meaningful gesture: moments before, the race announcer had instructed all of us in the start corral to turn to the individuals on our left and on our right, shake their hand and wish them good luck. It was a heartening display of sportsmanship, one that reminded us we’d be competing for much more than a finisher’s medal over the next 12 hours.

Ironically, no race in the world gets its name more right or more wrong than the Comrades Marathon. First run in 1921, the event was the brainchild of World War I veteran Vic Clapham, who wanted to create a unique test of physical endurance to commemorate his fellow South African soldiers killed in the war and to “celebrate mankind’s spirit over adversity”. Clapham envisioned a grueling physical and mental challenge, yet at the same time one accessible to any well-trained recreational athlete. Now in its 92nd year, the race has succeeded beyond its founder’s wildest dreams.

On the other hand, Clapham apparently wasn’t a stickler for details, at least when it came to naming his event. This distinction may seem trivial to non-runners, but a “marathon” by definition is 26.2 miles (42.2 km), much like a day is 24 hours or a ton is 2,000 pounds. Comrades, by contrast, is the world’s largest ultramarathon and over double the distance of a standard marathon. The course changes slightly each year, with this year’s course leading its runners nearly 54 miles (87 km) from the coastal city of Durban to the capital city of South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal province, Pietermaritzburg.

So calling Comrades a “marathon” is a bit like calling Godzilla a “lizard.”

View of the Durban coastline from our hotel room at the Southern Sun Elangeni

My earliest recollection of the race was a 2010 Runner’s World feature on running icon Bart Yasso, who after a debilitating battle with Lyme Disease chose Comrades as his last official race. Trying to wrap my mind around the concept, I came away from the RW article with a Mad Max-meets-Cormac McCarthy sense of Comrades as an event for elite athletes and uber-fit desert warriors whose bronzed skin could convert the sun’s heat directly into raw physical energy. Ninety km in less than 12 hours? Who were these freaks?? I wasn’t immediately smitten because, well, Comrades was clearly way beyond my abilities—I’d yet to even run a marathon at that point. But the article stayed with me.

Fast forward to March 2013. Katie and I stand on the deck of the Russian research vessel the Akademik Sergey Vavilov, both of us speechless as we soak in our first view of Antarctica. A tall, good-looking fellow in a heavy jacket and pajama pants strolls up alongside us, sharing in our wonderment. The three of us get to talking—he has an awesome accent which adds to his charisma—and we learn he’s from South Africa.

The conversation naturally turns to running (we’re there to run the Antarctica Marathon, after all), and Rory regales us with entertaining tales of his favorite race back home, the absurdly challenging Comrades Marathon. I’m familiar with the race, though do I know anyone who’s actually run it? I’m not sure. In any case, it’s clear from the fire in his eyes and his animated tone that Comrades is Rory’s pride and joy—so much so that he’s completed the race a mind-boggling 12 times. Ten finishes was enough to earn him what’s known as a Comrades “green number,” which is now his to keep and which he can even bequeath to his three sons in his will.

Meeting someone who’d not only attempted Comrades but who’d completed it, and who’d not only completed it but done so 12 times, lubricated the gears in my brain and brought them spinning to life. For the first time the idea of Comrades—of someone like me running Comrades—started to make sense.

Fast forward to 2016. We’d stayed in contact with Rory, broken bread together during one of his business trips to Los Angeles, and learned he’d been head of security for President Nelson Mandela before starting his own private security firm in South Africa, with clients around the world. Meanwhile, the seed he’d planted in my brain that day on the Vavilov had blossomed into an uncontrollable weed. I’d committed to fly more than halfway around the world to run the longest foot race of my life. And Rory, upon hearing the news, had generously offered to host us during our stay. Of course we’d jumped at his offer.

I wouldn’t have wanted it any other way.

Zinikele: Give it all you’ve got

“Shosholoza” followed the South African national anthem and segued seamlessly into the timeless piano of “Chariots of Fire.” More goosebumps. The restless crowd around me remained still; the butterflies in my stomach did not. I distracted myself by recalling the “Count-Down” instructions from the 1961 race, which we’d received with our souvenir magazine. These included:

4.50 a.m.: Have your last cigarette.

5.15 a.m.: Amble along to the start.

5.54 a.m.: Make sure you join in with a hearty cheer for the Mayor.

5:59 a.m.: Be good boys and smile nicely for the Press, they are some of the best friends we have got.

Like some blog posts, a little “Chariots of Fire” goes a long way, and two minutes later Vangelis’ heroic score was quickly getting on my overwrought nerves. Okay okay I’m inspired already, how many times does this repeat?

Bird’s-eye view of Corral B (photo: Jetline Action Photo)

Just as I started to think Vangelis himself had taken over the controls, the music faded. A brief hush was followed by the amplified sounds of a rooster crowing—actually, not a rooster, but the recorded tones of Max Trumbull, who at the Comrades start line in 1948 nervously let loose with his rendition of a crowing rooster (such is the anticipation of running 90 km). By popular demand, Max continued the tradition until his death in 1985, and to this day his recorded rooster crow starts every Comrades Marathon.

Like the first notes of a rock concert, which release the hounds of adrenaline and bring the crowd to its feet, Max’s cock-a-doodle-doo elicited pent-up cheers from the restless throngs. And the ensuing crack of a gunshot, fired promptly at 5:30am, opened the floodgates for the tidal wave of runners to pour through, red and white confetti raining down on the heads of the speedy runners in corral A.

Hurry up and wait, I thought as we pressed together, shuffling en masse toward the start line. There was a method to this madness: Comrades requires a qualifying time—for the marathon distance this is sub-5 hours—and runners are seeded in one of eight alphabetical start corrals according to that qualifying time, faster runners at the front (starting with corral “A”) and slower runners at the back (ending with corral “H”). I’d earned a solid corral C seeding with my 3:31 finish at January’s Louisiana Marathon.

As we crossed the start mat I glanced down at my Garmin: 1:58. Off to a good start, just two minutes lost.

Comrades is both cruel and unusual in many respects. One is the timing of the event. In most races, your official time starts not when the starter’s pistol fires (known as “gun time”) but rather when a timing chip on your bib number or shoe sends a signal that you’ve physically crossed the start line (known as “chip time”). Chip time is what matters, not gun time. In this way, slower runners who start closer to the back are not penalized the extra time it takes them to reach the start line.

Not so at Comrades. The race has a strict 12-hour time limit (a 13:20/mile pace this year); everyone’s time starts with the opening gunshot and ends when they cross the finish line mat. Add to that the race’s seeding system, which starts faster runners toward the front and slower runners toward the back, and you create a tense situation in which those runners who most need the extra time—the slower runners in corrals G & H—have already lost valuable minutes by the time they reach the start line.

Luckily the start corrals flow as smoothly as any in racing, inspired in part by the fear of gun time. It typically takes no more than eight minutes for everyone to cross the start line.

Comrades 2017 had begun, and we were all on the clock. We passed the VIP tent where, thanks to Rory’s connections, he and Katie stood watching the start with Comrades officials and celebrities, including 9-time winner Bruce Fordyce. I thought of the race’s one-word slogan: Zinikele, a Zulu word meaning “Give it all you’ve got”. I intended to do just that.

87 km to go. T-minus 12 hours to euphoria or heartbreak.

Google-ese translation of “Zinikele”—not the best slogan for when the going gets tough.

Farewell to Durban

Once clear of the start line, the stampede of runners surged forward through urban Durban, its downtown district nondescript in the early morning darkness. I split my focus between the other runners and the asphalt in front of me, taking care not to step on the back of someone’s foot and end my day before it had begun.

A fellow to my right dropped his water bottle, the unfortunate container barely striking the asphalt before someone inadvertently kicked it, sending it careening off another runner’s ankle like a pinball and skittering out of view underfoot. The rapid-fire sequence reminded me of the puck drop in a hockey face-off.

The compressed crowds worked to my advantage by preventing me from going out too fast, a huge no-no in a race like Comrades. In fact, it’s the one piece of advice you’ll hear repeated most often around the expo and throughout race weekend. I’d listened to enough podcasts and pre-race advice to have the concept of patience drilled into me. So I knew there’d be no shot of me flying out of the chute with my hair on fire.

Respect the distance, don’t fear the distance.

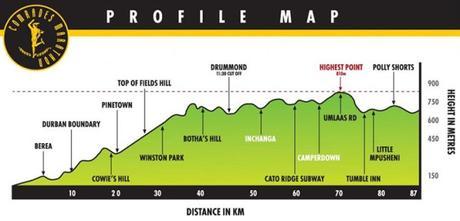

The KISS (Keep It Slow, Stupid) rule is solid strategy for almost any ultramarathon, but particularly for this year’s Comrades Marathon. Why? Because another cruel and unusual aspect of this race is the course.

Unlike other races which typically use the same route every year, in alternate years the Comrades course reverses direction between Durban at sea level and Pietermaritzburg at an elevation of 2,100ft. So whereas this year’s race started in Durban and ended in Pietermaritzburg, next year the opposite will be true. For obvious reasons, the route from Durban to Pietermaritzburg with its 2,100ft of net elevation gain is labeled the “up” run, while the opposite direction is known (cleverly enough) as the “down” run.

Course elevation profile for the 2017 Comrades up run

Many Comrades coaches and veterans will tell you that the first 42 km of the “up” run is the toughest road marathon you’ll ever run—and that your immediate reward for conquering those 42 km is another marathon and change to the finish. This is a grueling concept both mentally and physically, and I understood that while my performance in the first 37 km wouldn’t necessarily make my race, it could very easily break it.

“Essentially, the ‘up’ run is all about self-control,” writes he who would know best, 9-time champion Bruce Fordyce. “And this control has to be exercised in the first half.”

I’d chosen the “up” run based on Rory’s advice. Apparently, as exhausting as the steady climb from Durban to Pietermaritzburg can be, the uphill struggle is far preferable to the discomfort of descending those same hills with 50 km already in your legs. Downhill running damages the leg muscles like nothing else, and requires a whole different type of training than uphill running. So by reversing the direction of the route, the Comrades organizers essentially create a whole new race.

And speaking of hills—while big-game hunters dream lustily of Africa’s Big Five (buffalo, elephant, leopard, lion and rhino), Comrades runners have nightmares of a different Big Five. These are the five most notorious hills along the route, and they eschew muscular monikers like “Heartbreak Hill” and “Widowmaker” in favor of more dignified, understated names: Cowies Hill, Fields Hill, Botha’s Hill, Inchanga and Polly Shortts. And yet despite their innocuous names, each of the Big Five makes Boston’s Newton Hills look like zits on a lion’s back.

Comrades veterans will tell you that while the hills themselves are bad enough, it’s their placement along the course that will have you talking to yourself. Three of the Big Five (Cowies Hill, Fields Hill and Botha’s Hill) await in the first 37 km of the “up” route, with Inchanga positioned just after the halfway point and Polly Shortts just before the 80 km mark, the last real climb before the finish.

Bruce Fordyce, Katie and Rory enjoy the VIP seats

But as intimidating as the prospect of tackling them on race day can be, it’s important to appreciate that the Big Five aren’t the only hills on the Comrades course—and in some cases they’re not even the worst. As I’d quickly learn, just because it doesn’t have a name doesn’t mean it can’t kick your ass. Comrades is like death by a thousand cuts, with a few machete blows thrown in for good measure. And for many runners, the line between success and failure is razor-thin.

Given the course’s unusual length (54 miles) and the oversized reputation of the Big Five, it didn’t feel natural to divide the route mentally into five 10-milers as I had at last year’s Ice Age Trail 50; rather, I couldn’t help but break it down in my head as six stretches of variable distance separated by each of the Big Five.

We left the city streets of Durban via the on-ramp to the N3 highway and soon after began our first test of the day, the steady climb toward the Tollgate Bridge. Here I remembered Comrades coach and official course measurer Norrie Williamson’s advice from the expo two days earlier. He’d called Tollgate the first “reality check” of the day, telling us that over 80% of runners will start too fast and destroy their best time by Tollgate.

And I could see why. The climb up to Tollgate is gentle enough to be deceiving, yet steep enough to do real damage to the reckless runner. With early adrenaline on your side, it would be all too easy to find yourself powering up the gentle climb toward Tollgate’s double arches. And by the time you realize you’ve made a mistake, it’s too late.

83 km to go.

Tollgate Bridge (photo: KZN: A Photographic and Historical Record)

Tollgate to Cowies Hill

Walk once before the sun rises, Rory had advised. And so I took 30 seconds to slow down on my way up to Tollgate, my mind protesting this early white flag. We walking already? Really, tough guy?

Pacing groups at Comrades are known as “buses”, and I hoped to stick close to the 9-hour bus throughout the race. Glancing to my left I saw the 10:30 bus pass me and realized that, if anything, I may have started out too cautiously. Which was fine with me—I had 80+ km to make up the difference. Energy wasted now was energy I wouldn’t have later. Once that muscle glycogen burns, it’s gone and you’re not getting it back.

On my forearms were tattooed two pace charts, which I’d purchased at the expo from Comrades coach Lindsey Parry: one outlining a 9-hour finish (my “A” goal) and the other a 10-hour finish (my “B” goal). Needless to say, my “C” goal was to get across the finish line in less than 12 hours, and by any means necessary. Flying 17,000 miles just to earn a DNF (Did Not Finish) was not an option.

“I reached my 10,000 steps!” shouted a voice in the darkness to my right.

The “A” goal (left) and the “B” goal (right)

I accelerated slightly to put the 10:30 bus behind me and sipped at the Tailwind (sports drink) in my hydration pack. I’d elected to wear the pack for at least the first half of the race, in part so I’d have a steady supply of Tailwind to sip on, but also to carry the baby food pouches and PB&J sandwiches I’d prepared the night before.

I could always drop the pack with Katie and Rory along the course, but I was reluctant to disregard the most battle-tested piece of racing advice: nothing new on race day. Nougat bars and biscuits hadn’t struck me as appealing aid station fare, and my own menu of snacks had served me well at the Ice Age Trail 50. So I wasn’t about to reinvent the wheel—though as it turned out, I’d end up having to fix a flat tire or two along the way.

C’est la vie. It’s the ultrarunner’s mantra: Expect the unexpected. Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong. And it’s up to you to make it right.

Just past Tollgate we reached the first of what would be 46 aid stations. I’d heard it said that the Comrades aid stations are so long, you can look up from the end of one and see the beginning of the next. Turns out this is fake news—there’s plenty of space between aid stations, particularly later in the race when you need them most.

Which brings us to the water satchels. I know some folks—particularly Americans who aren’t used to them—deem the drink satchels to be another cruel and unusual element of Comrades. But I actually preferred them. The satchels are small plastic pouches filled with water or Energade (the South African equivalent of Gatorade), and you use your teeth to tear open the satchel to access the liquid. After one or two tries at biting open a water satchel on the run, you’ll be a pro.

In the early miles, the satchels provided not just hydration but also entertainment. Seeing newbies bite open a satchel awkwardly only to take a full spray of water in the face, I couldn’t help but laugh. And the occasional {POP} of someone stepping on an unopened satchel in the darkness was like the occasional firework. I stepped on a couple myself, dousing my ankles in water and Energade.

WOW, congrats indeed Louis! (photo: Jetline Action Photo)

Exiting the wide highway surface of the N3, we downsized to the more narrow, two-lane M13 (Jan Smuts Highway). I was happy to trade in excess elbow room for a more tree-lined stretch of road, though I’d been warned about the “cat’s eyes” (reflectors) between lanes, which are easy to trip over in the dark.

My pre-race hydration began to take its toll, and I ducked into a porta-potty on the side of the road, emerging less than a minute later to see the 9-hour bus pass me by, leading a large group of runners. Huh? Apparently I wasn’t the only one trying to figure out my pacing in the early going.

We made our way through Westville as the sun peeked above the horizon, transitioning onto the Old Main Road that connects Durban and Pietemaritzburg. Palm trees lined the road, and coming from SoCal I felt right at home. In general, South Africa is a very easy country to travel in as an American—most of its people speak English, the street signs are in English and the weather (particularly in the winter) is temperate.

“Hey there Michael, where you coming from?” asked a voice behind me in a South African accent—or was I now the one with the accent? It took me two heartbeats to catch up to the question and realize it was directed at me, my blue bib number on front and back announcing me as an international runner with exactly zero zilch zip nil nada Comrades finishes.

“California,” I responded. “United States,” I followed up quickly, not wanting to come across as that ugly American who expects all the world’s citizens to know where California is. I chatted with my new friend—a South African native and 6-time finisher—for a few seconds, and he and I wished each other luck on the journey to Pietermaritzburg.

Even the bib numbers at Comrades are fraught with meaning. White bibs identify South Africans, blue bibs international runners. Not only that, but yellow bibs identify Comrades veterans who have completed the race nine times and are competing for their green number. And green bibs, of course, are for those who have already achieved that feat. The bibs also list your start corral and the number of Comrades medals you’ve earned.

In a race as grueling as Comrades, you take motivation anywhere you can get it. And all along the course as the going got tough, I found strong motivation in the runners with 10+ or 20+ finishes on their bibs, chugging along purposefully. If they can do this 20 times, I can damn well do it once.

The best thing that can be said about the first 15 km of the up run is that, barring the occasional undulation, the climb is so gradual and consistent that after a while you hardly notice your own steady battle against gravity.

73 km to go.

Cowies Hill to Fields Hill

At last we reached the base of Cowies Hill. With the sun rising and the first of the Big Five stretching ahead of me, I felt like Comrades had officially begun. Passing the road sign announcing Cowies, I glanced up to see a steady stream of runners flowing up the hill. I forced myself to power walk for another minute as I snapped a photo. Then I pushed forward, eager to see what all the fuss was about.

After so much time spent hyping up the Big Five in my mind, I was disappointed to discover that its first three members arrive with very little fanfare. The first 37 km of the up run are such a steady ascent, I’m honestly not sure I would have realized we were on Cowies if I hadn’t seen the sign and heard the chatter around me. Cowies will definitely make you work, don’t get me wrong, but it may be more memorable for its subsequent downhill than for the steepness of its ascent.

Powering up Cowies Hill

Powering up Cowies we entered Pinetown, where throngs of spectators stood on both sides of the road, cheering loudly. One of the many amazing and unforgettable aspects of Comrades is the support of the locals—untold numbers of supporters line the course, and I was reminded of Patriots Day in Boston.

A group of strong-voiced young women sang “Shosholoza” a cappella, providing motivation and their own hand-clap accompaniment as we passed.

Cowies is neither the steepest nor the longest of the Big Five, and the mile+ ascent was challenging but doable. Then we were headed back downhill, with sweeping views of Pinetown to our left before the course again leveled out and resumed its ascent.

Shortly after Cowies we passed the first of the six cutoffs along the course—these are designated points that all runners must pass by a certain time, otherwise they’re pulled from the course and disqualified. And I pondered which would be worse: being pulled at the first cutoff of the day, or being pulled at the last.

Channeling my inner toddler, I downed my second baby food pouch of the morning. On longer runs, baby food is easier to digest than sugary gels, since it’s real food. I’d planned on a schedule of one pouch every five miles (8 km), supplemented with Tailwind every mile plus peanut butter & jelly. In this way, I hoped to avoid the aid stations for as long as possible.

Let’s hear it for wishful thinking.

The stretch through the commercial sector of Pinetown, with its businesses and car dealerships, was fairly uneventful. A generous but deluded spectator offered runners his jug of whiskey, the fellow next to me responding in a gentlemanly South African accent: “Ah, fuck you mate.”

You never run alone at Comrades (photo: Jetline Action Photo)

Continuing on the Old Main Road, the commercial, industrial and residential scenery struck me as wholly familiar: Pinetown could easily be blue-collar America.

Then it was back onto the M13 where the longest of the Big Five awaited. An official race km marker announced Fields Hill ahead, and I almost felt like a patient waiting for the doctor. Fields Hills will see you now, sir.

Fields Hill is the longest of the Big Five, and I honestly couldn’t tell you where it ends. Nor apparently can the organizers—look at the official Comrades elevation map above, and you’ll see an arrow pointing into the middle of a steady ascent with the label “Top of Fields Hill”. I do know I was running and power-walking up that sumabitch for too long—though again, I had such great expectations for the Big Five that it really didn’t feel so bad once I got on it.

Here I followed another sound piece of advice from Comrades coaches Parry and Williamson: I tried to keep my effort (rather than my pace) steady as we wound our way up and around the hill toward the summit.

I was also distracted by the fact that I’d expected to see Katie and Rory at the base of Fields Hill, around the 20 km mark where we’d planned to meet. Once we began our ascent I continued to keep an eye out for them, with no success. Finally I pulled out my phone and texted Katie on the fly. “61 km to go! Where are you?” Then a few minutes later, “60 km to go! Phone’s going off.” No overages on the international data plan, please.

I speak of “km to go” because the distance markers are yet another cruel and unusual aspect of Comrades. The markers are big and red and easy to see from far away, all of which I appreciated. But rather than celebrating how far you’ve come, the distance markers at Comrades confirm how much farther you still have to go. Psychologically, it’s daunting to be reminded of distances like 80 km and 70 km so early in the race. And it was only once I passed the “21 km” (= a half marathon) sign late in the day that I started to feel like that light at the end of the tunnel wasn’t another train.

No Katie and no Rory meant no familiar faces. More importantly, though, it meant I’d need to ration my remaining food, since I wasn’t sure if/when I’d see them next. Right around the midway point in Drummond I hoped, and yet I couldn’t be sure. One more baby food pouch plus a peanut butter & jelly sandwich should be enough to last me at least another 20 km… right?

63 km to go.

I was one of the few runners wearing a pack (photo: Jetline Action Photo)

Fields Hill to Botha’s Hill

By the time we reached Kloof, the sun was starting to flex its muscle in a cloudless sky. The day was shaping up to be warmer than forecast, a consistent breeze providing some respite from the heat. A relatively level stretch followed Fields Hill and led us through shaded, tree-lined neighborhoods. With the mounting heat and frequent palm trees, I got a sense of running in either Hawaii or Florida.

One thing I noticed as the km ticked off: none of the runners around me had wires dangling from their ears. Some of these folks would be out here lost in their own thoughts for nearly 12 hours, and yet none of them wore earbuds. Because Comrades demands (and deserves) every ounce of mental and physical focus you’ve got, and experiencing it from under earbuds would be like attending your own wedding while hopped up on pain meds.

(photo: Jetline Action Photo)

Checking the pace bands on each forearm, I realized I was slightly ahead of schedule for a 9-hour finish, despite taking things slow to this point. I continued to churn out ten-minute miles through Gillitts and Hillcrest, the latter disappointing me with its abundance of hills and lack of crests.

Even if you knew nothing about the race itself, you’d still notice a common theme along the Comrades route: many of the towns and landmarks have “hill” in their name. Crazy coincidence, that.

My focus now was on getting to the 37 km mark, where the course leveled out. And all that stood between me and that goal was Botha’s Hill.

Like Cowies and Fields, Botha’s arrived with little fanfare. But it was steep and winding and nearly 3 km long, not to mention it had the sun on its side. Once again steady effort plus a bit of power-walking carried me to the top, where the shade of tree cover awaited us. So too did the well-dressed boys of Kearsney College, a private boarding school founded (like Comrades itself) in 1921 and located at the top of Botha’s Hill. Maybe it was my mindset coming off the hill, but none of Kearsney’s finest seemed particularly psyched on a hot day to be greeting a bunch of sweaty runners while dressed in a suit and tie.

And with that I’d reached the 37 km mark, the toughest miles of the Comrades up run in my rearview mirror. My rush of accomplishment, though, quickly yielded to sobering reality. Pietermaritzburg was still 50 km away. And the sun was still climbing in the sky.

50 km to go.

View overlooking Alverstone, 47 km to go

Botha’s Hill to Drummond

With the majority of the climbing behind us, the course continued to roll for the next couple of miles before treating us to our first extended downhill, the largely unshaded descent into Drummond. Here I was psyched to see Katie and Rory for the first time. I’d polished off my last baby food pouch several miles earlier and had tried a bite of my peanut butter & jelly. Bad idea—the consistency was like paste, and even with plenty of water to wash it down, my body had instantly rejected the idea.

Rory flagged me down, and I pulled over to catch my breath and refill my hydration pack before reluctantly moving on. With the heat intensifying I could tell my body was circling the wagons, approaching its Tailwind limit and with no appetite for either baby food or peanut butter. Even so, I decided to carry my pack until at least the 25 km-to-go mark, when I’d see them again.

My brief pitstop invigorated me, and I rode a surge of energy downhill into Drummond. Approaching the up run’s de facto halfway point, we passed two key landmarks on the Comrades course: the Wall of Honour and Arthur’s Seat.

Getting inspired by Rory’s Green Number plaque on the Wall of Honour

If you’re planning to run Comrades, take some time before or after the race to visit the Comrades Marathon Wall of Honour (you’ll likely be too rushed and too tired to appreciate it on race day). Erected along the side of the road just before Drummond, The Wall is a collection of plaques set in individual stones and decorated with the names of past finishers, along with their bib numbers. Yellow plaques signify runners with between one and nine finishes, while green plaques identify those who have earned green numbers. Best of all, anyone with an official Comrades finish can buy a plaque to be displayed on the Wall.

The Wall of Honour is a remarkable and ever-changing tribute to human endurance and to 92 years of Comrades finishers. And we were fortunate to have a host in Rory who drove us out to the Wall the night before the race, so we could take the time to appreciate it without having to commit to the official pre-race course tour.

Speaking of the course tour—the notion of spending several hours aboard a bouncy school bus, a captive audience for 87 km worth of ups and downs, sounded about as appealing as running the route with my laces tied together. I was intimidated enough by the hills without seeing them ahead of time, and I was more than happy to experience the entire course for the first time on race day.

Just past the Wall of Honour on the uphill is a small sign that, if you’re running with your head down or lost in thought, you could easily miss. The sign reads “Arthur’s Seat” and points left across the street. Carved out of the rock embankment along the road is a shallow recess where 5-time Comrades champion Arthur Newton reportedly used to rest during his runs. Legend has it that Comrades runners who greet Arthur and place flowers on his seat during the race will enjoy a strong second half.

“Good morning, Arthur” I greeted the former champ tiredly, tapping the rock face along with other runners and snapping a picture before continuing on my way. Superstition or not, this wasn’t the time to be taking chances.

Runners say “good morning” at Arthur’s Seat

I continued to chat intermittently with fellow runners, most of them from South Africa. With more than a marathon in our legs, none of the conversations were particularly deep, but I enjoyed meeting both veterans and first-timers as well as congratulating several 9-time finishers on their impending green numbers.

Glancing down at my pace tattoo, I saw I needed to reach Drummond in 4 hours, 35 minutes to stay on pace for a 9-hour finish. I glanced at my watch as we passed the third cutoff point: 4:28. So far, so good—not too fast, not too slow.

My 9-hour goal wasn’t an arbitrary one. Because another unique (and some might attest, cruel and unusual) aspect of Comrades is the finisher’s medal. The first thing you’ll notice is that the medal is likely the smallest you’ll ever receive, at roughly the size of a quarter. At the same time not all the medals are created equal, with different medals being awarded based on finish time.

The first ten finishers are awarded a Gold medal. Runners who finish out of the top ten but in less than six hours receive the Wally Hayward medal (silver center with gold ring), named after the 5-time Comrades winner who, in 1989 at age 80, also became the race’s oldest finisher in a time of 10:58:03.

Runners who finish in greater than six hours but less than 7:30 earn a silver medal, while runners who finish in greater than 7:30 but less than nine hours—my “A” goal—earn the Bill Rowan medal (a silver center with a bronze ring), named for the first winner of the Comrades Marathon who finished the race in 8 hours, 59 minutes.

A sizable gap separates the final two classes of medal recipients. Runners finishing in greater than nine but less than 11 hours receive a bronze medal, while the Vic Clapham medal (copper) goes to survivors who cross the finish line before the 12-hour cutoff.

Halfway home in Drummond—we look like synchronized runners (photo: Jetline Action Photo)

As if running 87 km weren’t enough to test your limits, competing to earn a particular medal (in my case, the Bill Rowan) adds to both the excitement and stress of the race—excitement for those who set realistic goals, stress for those who try to do too much. And heartbreak is all too frequent. Rory had recounted the story of his 2003 down run, when he’d missed his Bill Rowan by 12 seconds and had watched in horror as the puff of smoke from the 9-hour gun went off meters away from him.

According to Coach Norrie Williamson’s Comrades calculator, nine hours was a realistic goal based on my recent finish times. Given the travel and the heat, though, I knew Bill Rowan was a best-case scenario. Had the race been held in Southern California, that would have been a different story. But since I’m much better at running the ups than the downs, I figured I owed it to myself to give it a shot in this, an up year.

Cruising through Drummond, there was no missing the halfway point—it was rocking, the scene decked out in purple and gold with an inflatable arch, banners lining the course, music pumping, spectators screaming and an announcer greeting runners like we were celebrities, rock stars and supermodels. The raw energy was overwhelming but a definite pick-me-up. And I wish I’d had more time to appreciate it. There was some relief in knowing we were halfway home, but with still more than a marathon to go the relief was short-lived.

Then we were on our way again. “Welcome to the Valley of 1,000 Hills!” someone shouted. There it was again, another landmark with the word “hill” in it. And hadn’t we run that many already?

If I’d known about the one hill that awaited us, though, I might have opted for the other 1,000 instead.

42 km to go.

To be continued soon…