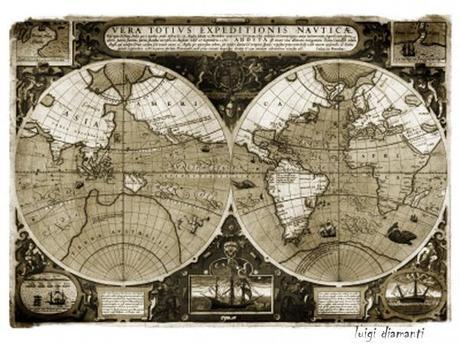

In medieval times cartographers often placed dragons and sea serpents in uncharted areas of their maps. While they may not have literally believed these regions to be populated by monsters, they understood them to be dangerous. Explorers went anyway.

I was reminded of those old maps by two wonderfully complementary essays from National Geographic that caught my eye this week. The first, Restless Genes, tries to explain this penchant for exploration.

“No other mammal moves around like we do,” says Svante Pääbo, a director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, where he uses genetics to study human origins. “We jump borders. We push into new territory even when we have resources where we are. Other animals don’t do this. Other humans either. Neanderthals were around hundreds of thousands of years, but they never spread around the world. In just 50,000 years we covered everything. There’s a kind of madness to it. Sailing out into the ocean, you have no idea what’s on the other side. And now we go to Mars. We never stop. Why?”

David Dobbs, the author, suggests that a specific gene called DRD4-7R “makes people more likely to take risks; explore new places, ideas, foods, relationships, drugs, or sexual opportunities; and generally embrace movement, change, and adventure.” Call us carriers, but Mr. Dobbs notes that genes alone can’t explain humans’ migratory past.

Technological advancement or stasis also plays an important part. Restless Genes recounts the tale of how early Polynesians migrated through the South Pacific, rapidly hopping from one island to another until they reached the Bismarck Archipelago and Solomon Islands where their advancement suddenly stopped.

Researchers theorize that the earlier migration had taken place among inter-visible islands. Whenever settlers reached a new island they could see others on the horizon and eventually made way toward them. Beyond the Solomon’s, though, nothing but open water can be seen even after weeks of sailing. It must have looked to them like the edge of the world. And although they did not have the technical ability to explore deeper into open water in search of new frontiers, the desire to do so did not lapse even after thousands of years. Once these Polynesians acquired more seaworthy vessels, their migratory island hopping continued.

The image of a people stranded on shore, longing to see beyond the horizon, but lacking the technical ability to set out makes me think of where mankind sits today in relation to the stars and also brings me to the second National Geographic essay, Crazy Far. Twenty four trillion miles far, to be exact. Or, said another way, the distance between our solar system and its nearest star. The author puts those miles into perspective:

“The fastest spacecraft ever built—the Helios 2 probe, launched in 1976 to monitor the sun—attained a top speed of 157,000 miles an hour. At that rate, a spacecraft headed to Proxima Centauri, the nearest star, would take more than 17,000 years, . . . a temporal span equal to the one that separates us from Cro-Magnon cave painters.”

It’s a daunting, unthinkable, and quite likely impossible task. Yet some serious people are doing more than just thinking about sending men and women to that far away place, they’re dedicating time and no small amount of money to make that impossible task possible. It won’t happen in our lifetime. But the will to go? That, apparently, is in our genes. All we need now are better boats.