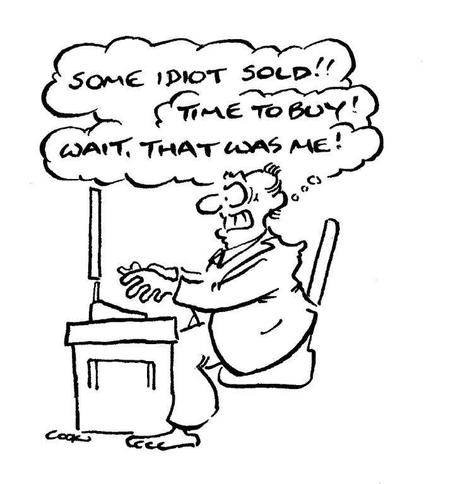

The problem's inside our own heads.

On Monday morning, Asian share prices collapsed. Global markets did likewise that night. By Tuesday morning I was in debt.

It was my first lesson in behavioural economics – the idea that investors are not rational human beings. Contrary to what I’d learnt at university, they are emotional ones.

I’m not talking about markets. I’m talking about people; people like me. That Tuesday, a colleague asked if I had seen the Japanese futures market. I presumed it had followed suit. And more, he said. That highly leveraged contract out-crashed everyone. It was probably the best buying opportunity of the decade.

I knew that, but making decisions in tough times is hard. From the sidelines I watched that contract rise several hundred percent over the next week. A rational investment decision would have bailed me out. I didn’t make one.

There are plenty of reasons.

There’s also “gambler’s fallacy”, like a slot machine addict playing the same machine thinking each roll will get them nearer to a jackpot. In fact, machines are programmed to reset the odds for every turn. It might be 1000:1 when you play it the first time. It will still be 1000:1 when you play it again.

You are not alone.

Don’t rule yourself out just because you aren’t a gambling addict. Most of us get stuck in irrational behavior ruts.

My 1987 gloom in was evidence of Daniel Kahneman’s “loss aversion”. Losses generate far stronger emotional responses than do the joys of winning. I’ve experienced this in sport and in business. Wins quickly become what happened yesterday; the impact of a setback can linger for days.

Other findings include “anchoring”, when we view the status quo as a benchmark, failing to see lateral alternatives available from a different perspective. Or the extremely common “confirmation bias”, where we only see evidence that supports our own view. That’s brought many a charismatic CEO undone.

One remedy is obvious.

Taking a big plunge on Nikkei futures in 1987 might have been too brave for me, but a small wager would at least have been a rational response. At the time, I was stuck in my own head.

An old saying says your head is like a dangerous neighbourhood. You shouldn’t hang around in there alone. One alternative is to value other opinions as much as your own.