The idea of “comedy” carries with it a sense of lightness, easy laughter, or distance. It also carries with it the implication that the audience who is listening, watching or reading is primed to laugh. They expect to be entertained and amused, to hear something funny.

When people are in the midst of tragedy, or dealing with its aftermath, their expectations are different. They seek comfort. Connection. Strength. Relief. Information. Laughter can seem inappropriate — especially lighthearted laughter or any sort of mockery. But laughter can also provide comfort, connection, strength, and relief. And sometimes humor — as opposed to comedy or a joke — can also provide information, or a new perspective that enables coping. In other words, humor can allow us to stand a little askew — a stance that can help in surviving a tragedy, or in coping afterward. This use of humor is very human, but I also think, in many ways, it is particularly American.

In September 1857, the ship Central America, carrying 626 crew and passengers and almost $2,000,000 in treasure, went down in a hurricane off the southeastern coast of the United States. Sighting a ship in the distance, all of the women and children were put aboard the only three lifeboats they had. The men aboard went grimly about the business of bailing until the ship finally went down. Of the approximately 576 men cast into the waters when the ship went down, fewer than 10% survived to be rescued. But amid the terror of the wreck, a group of survivors remembered most what gave them hope and strength: humor.

One of the passengers on board the ship was the blackface minstrel Billy Birch. Along with other men, he had put his wife Virgina (with her pet canary firmly and safely tucked into the bosom of her dress) into a lifeboat. Cast into the sea with the others when the ship went down, Birch swam about until he found a bit of flotsam. Hailing other survivors in the nearby waters, he invited them expansively to have a perch on his “yacht” to rest, and apparently kept up a running patter of jokes and humorous comments as they waited hours in the cold and stormy seas for rescue. Years later, long after the stories of the night’s terror had dimmed in the popular imagination, occasional re-tellings surfaced about the incongruity of the famous actor and his impromptu floating stage, of his indefatigable good humor and laughter.

The story resonated because it appealed to something deep within Americans’ sense of themselves. Unlike the legendary British “stiff upper lip,” Americans seem to pride themselves on meeting disaster and danger with resolve and quips and humor. Events of the last week show that this is still true.

When on April 15, the Boston Marathon was violently disrupted by bombs exploding near the finish line, the initial response across the nation was of course shock, empathy, sadness, and anger — simultaneous with pride in those who helped and in the resilience of survivors who woke up “happy to be alive” and runners who had not been able to finish the race but who, only a day or two later, were discussing online how to finish the race in honor of the fallen, which included an 8-year-old boy, and out of determination not to be stopped. Humor quickly came into the national conversation as well, as one of the slain, Krystle Campbell, was described over and over as having “a great sense of humor” as one of her most important and defining characteristics.

Stephen Colbert weighed in the next evening, with a tribute to the people of Boston in his opening monolog that is being shared on websites and in news reports around the world. The monolog has already been characterized as “masterful,” “meaningful,” “eloquent,” “touching,” “patriotic,” “moving” — and “humorous.” I would argue that it is also quintessentially American. After opening with a serious statement of sympathy and one of determination that those responsible will be caught, Colbert used humor to remind Americans of what he sees as our core strengths, exemplified in the city that was the “cradle of the American Revolution”:

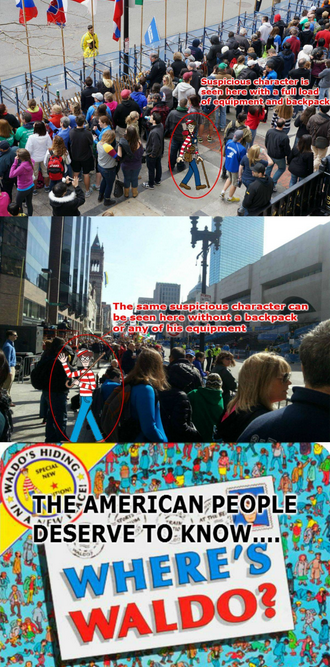

Whoever did this did obviously did not know s*** about the people of Boston, because nothing these terrorists do is going to shake them. For Pete’s sake, Boston was founded by the Pilgrims — a people so tough they had to buckle their goddamn hats on.And he invokes the American work ethic, again using humor to remind his audience that Americans work hard and play hard:But here’s what these cowards really don’t get, they attacked the Boston marathon, an event celebrating people who run 26 miles on their day off until their nipples are raw – for fun...Braggadocio and verve meet here, as Colbert winds up his audience. But he also uses the humor to remind Americans that though self assertion and in other cases, selfishness, seem at times to be at the center of our ethos — when the chips are down, being our brothers’ keeper is at the core of our value system:..And when those bombs went off, there were runners who after finishing a marathon kept running for another two miles — to the hospital to donate blood. So here’s what I know. These maniacs may have tried to make life bad for the people of Boston. But all they can ever do is show just how good those people are.….But these written excerpts don’t do justice to his performance, how funny it is, the accompanying visuals, or their effect on his live audience. You can see the whole monolog here: Colbert Nation….But not all the humor in the days since the tragedy has been of the uplifting kind — and for better or for worse, these are part of the American humor landscape as well. Some has been what most of us would find inappropriate and even cruel, like the parody mashup of Seth McFarlane’s Family Guy that adds unrelated clips of the Boston Marathon bombing (a hoax condemned by its creator). Others have tried to use humor to make a point, as in the “Where’s Waldo?” cartoon mashups that satirically remind all of the armchair-Internet-would-be FBI agents that their efforts to identify the bomber through available videos online are just as likely to do harm as good — that they are just as likely to target innocent bystanders as identify the real perpetrator(s), as we have access only to the news that has been reported and “news” that has been made up, not to the actual police and FBI reports.

Source: http://www.dailydot.com/news/4chan-boston-marathon-bomber-photo-evidence/

Mark Twain once said: “Humor must not professedly teach and it must not professedly preach, but it must do both if it would live forever.” The inappropriate or offensive efforts at humor in the wake of this tragedy will probably be remembered only as lessons in how we need to improve. Others, like Billy Birch’s arguably heroic use of humor to keep survivors’ hopes up in stormy seas, or Stephen Colbert’s efforts to remind Americans of their strengths in the face of adversity, will last somewhat longer. But the fact that humor is a part of the American ethos, the American response to tragedy or loss, it seems, will not change. And when we ourselves are crushed with the weight of the tragedy, we count on others to find some humor, to provoke a moment’s laughter and a moment’s ease.

Because, to paraphrase Leonard Bernstein’s defiant statement after the assassination of President Kennedy, the only “reply to violence” is to do whatever it is you do passionately “more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before.” Tragedy, facing death or destruction, doesn’t really change us, it distills us. It makes more who we are. And humor is, inescapably, a part of the American way of looking at the world.

© Sharon D. McCoy, 18 April 2013