Stand-up comedy derives much of its power from the use of the performer’s personal life. Sure, comedians stretch, embellish and outright invent some of the stories they tell on the stage, but most audience members conflate the act they see on stage with the person they imagine the comedian to be off-stage. I believe that this is actually part of the continuing fascination of Andy Kaufman, who derived much of his power from shielding his personal interior life from view of the audience.

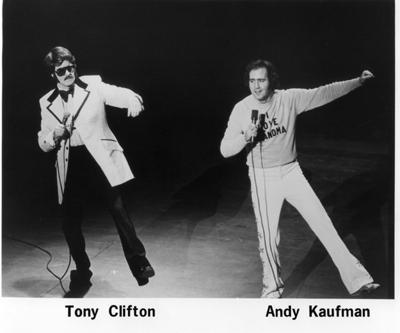

Such was the case with Kaufman’s “Foreign Man/Latka” persona, his Elvis impersonation, and definitely his portrayal of the rude and offensive lounge act Tony Clifton.

The Wikipedia entry on Clifton claims that the inspiration sprang from a real Tony Clifton, “a real lounge singer whom Kaufman encountered in the International Hotel in Las Vegas.”

There are stories — many of them told by Kaufman’s creative partner Bob Zmuda — of other people playing Clifton in performances. When negotiating his contract to play Latka on Taxi, Kaufman reportedly insisted that they hire Tony Clifton as a guest star. When Kaufman-as-Clifton arrived on set, he came with a pair of hookers from the Moonlite BunnyRanch and behaved so badly that Kaufman-as-Clifton was thrown off set. (See Zmuda’s Andy Kaufman Revealed! for a lengthy account.)

Most famously, Kaufman’s brother Michael played Clifton in the 1979 Carnegie Hall concert.

It’s an open secret that the Tony Clifton who continues to tour has been able to outlive Andy Kaufman, who passed away from cancer in 1984, because Zmuda can continue to play the character. I recently saw Clifton perform at the Comedy Store in Hollywood, and it was one of the more remarkable stand-up shows that I’ve seen — if one can classify it as stand-up. I arrived at the 11:30 show with the expectations of seeing a bad lounge act. Clifton delivered there, providing us with trite song choices and poor patter, but the performance was more than just ironic Vegas-lite.

At times, Clifton told super-progressive political jokes, displaying an insight into world politics that pushed beyond the partisan issues of the 2012 presidential election. At times, Clifton told super-regressive racial jokes, demanding that we question audience complicity when it comes to offensive comedians. Like Kaufman, Clifton continues to enjoy pushing audience boundaries. One of his showgirls pours hard liquor down the throats of attendees willing to test whether what comes out of the bottle is real or not. Clifton restarts the chorus of “Rhinestone Cowboy” to the point where it’s not funny and then it is and then it isn’t and then audience members find themselves overwhelmed by the sheer force of a man who is in his sixties — if he really is played by Mr. Zmuda. Even the use of puppets in the two-and-a-half hour show calls into question the differences between Zmuda and Kaufman and Clifton.

So, is Kaufman a puppetmaster whose on-stage creation refuses to die? Was he an anti-stand-up comedian, in that he created distinct characters to play on-stage rather than discussing elements of his actual life? If you are intrigued by the struggle between the joketeller and the jokes told — which comes first? — I recommend catching Clifton in the act. He’s rough and rude, but also remarkable.

Matthew Daube (Ph.D., Theater and Performance Studies, Stanford University) has taught in half a dozen different departments at Stanford University, including Thinking Matters and the Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity. His dissertation, “Laughter in Revolt: Race, Ethnicity, and Identity in the Construction of Stand-up Comedy” argues for the recognition of stand-up comedy as a distinct performance mode that emerged in the United States following World War II, linked to issues of race and focused on the performance of self. He is particularly interested in the intersections between humor and the performance of identity, and has published articles on the use of ethnic stereotype by the Marx Brothers and the role of the audience in stand-up comedy.