"We've always loved horror. It's just that horror, unfortunately, hasn't loved us."

That opening line from Shudder's new documentary Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror says it all. It comes from Tananarive Due, an African American horror fiction author who has an NAACP Image Award and steadily growing list of books to her name. She's specifically speaking in this instance about the black viewer's love-hate relationship with the horror film genre. As Horror Noire rather effectively argues by way of repurposing footage from the opening of Scream 2, the black horror fan has been yelling for the stupid white people on the screen to not go down that scary hallway alone for far too long. Just once, couldn't the people on the screen look like them AND when they do could they please not die right away!

By extension, the entire documentary is the story of how an entire race of people have been habitually disrespected by the horror genre until very recently. If nothing else, Horror Noire will make you appreciate just how truly groundbreaking Get Out was two years ago. Before it, the documentary argues, every gain for black people in the horror space usually came with some serious caveats or backslides:

Finally get a black lead/hero in 1968's Night of the Living Dead, but he dies at the end via a glorified lynching. Moreover, the historic success of the film doesn't really lead to any knock-off projects with black leads.

Finally get a bunch of movies being made for black folks in the 1970s with the blaxploitation pictures, but they're mostly produced by a white dude and traffick in some seriously harmful stereotypes.

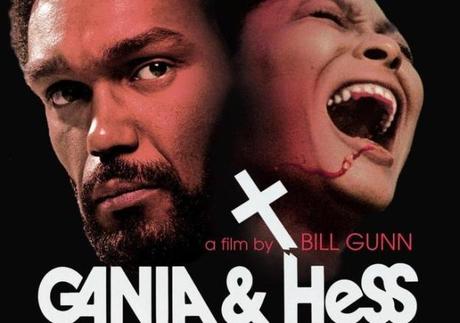

Finally get a blaxploitation picture made by a black filmmaker and featuring fully realized black characters - Bill Gunn's 1973 vampire drama Ganja and Hess - but the nervous producers recut it a more conventional horror film called Blood Couple, leaving just one copy left of the original version in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Finally see black people in more mainstream horror movies in the 1980s, but they never get to be the main characters and mostly just exist to be a sassy best friend and/or eventually die, often sacrificing themselves for the white lead thus becoming the Sacrificial Negro.

Finally see a slasher series villain with a black face in Candyman, but the movie reinforces stereotypes about black men being the death of white women and features certain scenes - why would the vengeful ghost of a black artist killed by white people come back to kill black people in the projects? - which betray that the whole thing was made by white people who intellectually but don't emotionally understand the story.

Finally get slasher movies to acknowledge how silly it is to always kill off the black characters, yet still have to fight tooth and nail to produce a slasher movie featuring a final girl who is black, like Demon Knight's Jada Pinkett Smith. Plus, despite the slasher's newfound self-awareness, a lot of its black characters still end up dying or simply disappearing from the story, like Duane Martin's Scream 2 cameraman.

And so on.

Director Xavier Neal-Burgin, a USC grad with a bunch of short films and TV episodes on his CV until now, chronicles this depressing history via interviews with several prominent black film professors and educators as well as many of the directors, writers, and actors responsible for the history of black representation in the horror genre.

Unlike similar documentaries of this kind, such as Eli Roth's recent AMC series The History of Horror, Neal-Burgin makes the inspired choice to break from convention and not solely march forward with the more expected formula: talking head interview, old film footage, talking head interview, old film footage, rinse, repeat. While that is undeniably present, he also complements it with scenes of famous black filmmakers or actors paired off in twos, sitting in a Siskel & Ebert-esque screening room and simply talking to each other about their own experiences in the industry or some of their famous black horror movies.

This often serves to reinforce the larger point being made. For example, Dawn of the Dead's Ken Foree and The Thing 's Keith David discuss what it was like being a black man at a time when blaxploitation pictures were popular, sharing stories of walking down the street and being called "pimp" by random white people as if that was a complement.

Elsewhere, several 80s horror actors reminisce together about how they were simply happy to have a job back then, regardless of how quickly their character died. Most tellingly, Poltergeist co-star Richard Lawson, who plays one of the members of Beatrice Straight's team of paranormal investigators, recalls feeling frustrated, but not angry over being sidelined. As he tells it, he'd read a script like that and wonder why he couldn't be the dad or why the family had to be white, but it was the early 1980s. Such things were but pipedreams then. "Our time will come," he recalls thinking.

That time finally came with Get Out, Jordan Peele's instant classic about the slave trade reborn in the modern day with a bit of sci-fi/horror twist. In so many ways, Get Out rejects all the stereotypes of black horror built up over a century of film history and surprised even those who'd worked in the genre for decades. As Peele admits, "I made Get Out for everybody in the audience. I didn't want anybody to see the film and not get it. But I really made the film for black audiences. If black audience didn't get it and didn't like it, that's a fail."

Hearing and watching the faces of so many of the black filmmakers and educators discuss what Get Out meant to them is the highlight of the documentary, but only because Neal-Burgin does such an excellent job of contextualizing the history of black horror to that point. Finally, Get Out was a black horror movie which required no caveats, no qualifiers, no hand wringing. It was the movie an entire race of people had been waiting for, and just as blacks supported white-led horror films for decades white audiences showed up for Get Out and were cheering for Daniel Kaluuya right alongside everyone else.

You can quibble with other aspects of Horror Noire. Certain prominent films go unreferenced or underexplored. The Serpent and the Rainbow and The People Under the Stairs, for example, are only briefly addressed and written off as Wes Craven's well-meaning, but still problematic commentaries on race relations. An explicitly race-related, post- Get Out film like The First Purge earns just a single mention.

However, all documentaries of this type are forced to pick and choose which projects to highlight, and the central thesis of Horror Noire is clear: black audiences have had to wait too damn long to finally have the horror genre love them back. Thanks to the game-changing success of Get Out, hopefully, that waiting period is a thing of the past.

Jordan Peele is certainly doing his part, with his follow- up feature Us due in March and a Candyman remake in development and due next year. While we wait to see those, Horror Noire makes a persuasive argument for other black horror films worth checking out. Personally, I'm in the middle of Tales from the Hood right now and can't stop kicking myself for sleeping on this absolute gem of an anthology horror film for so long, and The Girl With the Gifts just went into my queue. Thanks, Horror Noire.

Horror Noire is currently available on Shudder. What are some of your favorite black horror movies? Or even some you've always been meaning to watch? Let me know in the comments.

Grew up obsessing over movies and TV shows. Worked in a video store. Minored in film at college because my college didn't offer a film major. Worked in academia for a while. Have been freelance writing and running this blog since 2013. View all posts by Kelly Konda