Many researchers believe that certain human traits act as a signpost, advertising the fact that the individual has good genes, or is healthy, or just generally great. As such, finding these traits attractive will result in mating with healthy individuals with good genes. Then evolution kicks in, and the advantages of being attracted to these traits (and possessing them) spread throughout our population until it’s a ubiquitous characteristic of humanity. This is sexual selection.

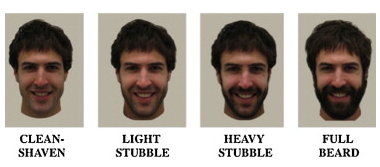

For example, two researchers from the University of New South Wales recently conducted a study into how attractive men and women find beards. Dixon and Brook’s (2013) results indicate that the more beard a guy has, the more masculine and healthy they’re considered by both men and women alike. The sexual selection implication of this is that a guy with full beard has the genes and health needed to grow it, thus advertising just how good beardy is as a mate.

Except that women don’t find full beards most attractive. Sure they rate them as most masculine and most healthy, but heavy stubble, rather than full beard is rated as the peak of attractiveness. The researchers hypothesise that this is because picking a mate who is too masculine isn’t necessarily a good thing. They may be more likely to get into fights, take risks and wind up widowing the wife and leaving her to raise his beardy babies alone. Going for a stubble-sporting mate may be a safer bet.

In research, it’s important to define “beard” with pictorial examples

But before all you hip, happening bachelors start growing just the right amount of stubble to seem sexy; it’s worth noting that there’s a flaw in the evolutionary reasoning behind this research. Cast your mind back to how evolution actually works:

- Everyone is slightly different.

- Those differences lead to different rates of survival and reproduction

- In subsequent generations, more/less people have those differences depending on if they increased/decreased rates of survival and reproduction

Spotted the problem yet? Evolution works through the differential survival/reproduction of different individuals. It’s really hard to make a case for evolution (in the form of sexual selection) influencing how attractive beards are without showing that having that super-attractive heavy stubble actually increases your chance of having babies. And these researchers didn’t do that.

Now, waiting for the next generation to pop out takes time so most researchers try to think of shortcuts. Typically this is “look for universal traits.” After all, point 3 indicates that a beneficial, evolved trait will spread throughout the population. So if being attracted to beards is beneficial and thus has evolved, it should be something true for all women. However, given 80% of the women interviewed by the beard study were European, I hardly think they’ve identified a universal consensus on what is attractive.

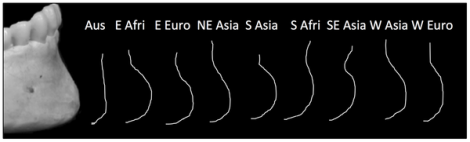

Indeed, there are many examples of researchers identifying a trend in a limited sample size; but having it disappear when they ask a greater variety of women (or men). For example, a guy develops a broad chin when they have a lot of testosterone during development (Enlow, 1982); making it a sign of well….testosterone! Having testosterone is generally a good thing for men, so if a woman is attracted to a broad chin they will be sure to bag a mate who will ensure her children have the genes needed for good testosterone.

And sure enough, studies indicated that broad chins were attractive (Rhodes et al., 2003). But then Thayer and Dobson (2013) analysed the skeletons of men from around the world and found major differences between their chins. No single type of chin – broad or not – was universal. This is the opposite of what we’d expect if evolution was spreading traits throughout the population; indicating that having a broad chin is not being (sexually) selected for.

The outlines of chins from around the world!

It’s not just studies of the influence of sexual selection that suffer from this problem. Attempts to identify the impact of evolution on other behaviours and traits typically also use the “look for universals” approach; but make conclusions before having examined a large enough sample.

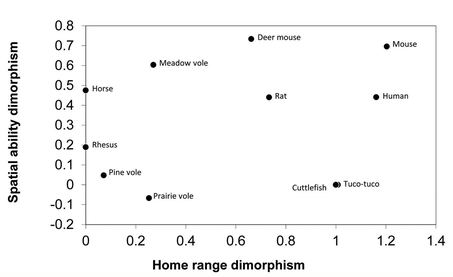

For example, men have better spatial memory than women. Not quite enough to justify tired stereotypes about women and maps, but the difference is still significant. This is a universal characteristic, and was long thought to be the result of evolution. Back when we were hunter-gatherers, men had to hunt over large territories; requiring them to develop better spatial memory to remember where everything was. Conversely women gathered, which didn’t involve traveling over quite so large an area.

But then more widespread study examined dozens of animal species and found spatial reasoning was not correlated with territory size. Males always had better reasoning, regardless of whether or not they had a larger territory than the females. Eventually the researchers realised extra testosterone associated with having balls was causing the effect and were able to make a female rate better at remembering where things were by injecting her with the stuff (testosterone, not testicles) (Clint et al., 2012).

Dimorphism = difference between genders. As you can see, there is no real relationship between different territory sizes and different spatial ability

So even when research does identify a universal trait it still isn’t necessarily an example of psychological evolution. It could be the result of chance, or testosterone, or something else. As such the only real way to investigate the influence of evolution on our mind is to look for evidence of steps 1 & 2 of evolution. To look for traits which actually give a guy (or a gal) an increased chance of producing children.

Sure, looking for universal traits is a good way for coming up with ideas about what may have been influenced by evolution; but that’s just the first step on a long road to show evolution is involved. So the next time you hear an evolutionary psychology story about why things are the way they are (like how rape evolved to give lesser-quality men a chance to reproduce) be skeptical. Ask for evidence of evolution actually taking place, not just “universal” traits. Otherwise their story is no different from fairy tales about why the leopard got his spots.

And thou shalt not use evolution to justify bollocks.

References

Clint, E. K., Sober, E., Garland Jr, T., & Rhodes, J. S. (2012). Male superiority in spatial navigation: adaptation or side effect?. The Quarterly review of biology,87(4), 289-313.

Dixson, B. J., & Brooks, R. C. (2013). The role of facial hair in women’s perceptions of men’s attractiveness, health, masculinity and parenting abilities.Evolution and Human Behavior.

Enlow DH (1982) Handbook of Facial Growth. Philadelphia: .W.B. Saunders

Rhodes G, Chan J, Zebrowitz L, Simmons LW (2003) Does sexual dimorphism in human faces signal health? Proceedings: Biological Sciences 270: S93–S95

Thayer ZM, Dobson SD (2013) Geographic Variation in Chin Shape Challenges the Universal Facial Attractiveness Hypothesis. PLoS ONE 8(4): e60681