Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, John Jabez Edwin Mayall, 1861. Photo: National Portrait Gallery, London.

I am on a definite Victorian kick right now but as I have a rule about not reading any fiction set in the same period as the one I am writing about, I have been instead turning my attention to non fiction, which has the additional bonus of being (mostly) RESEARCH.

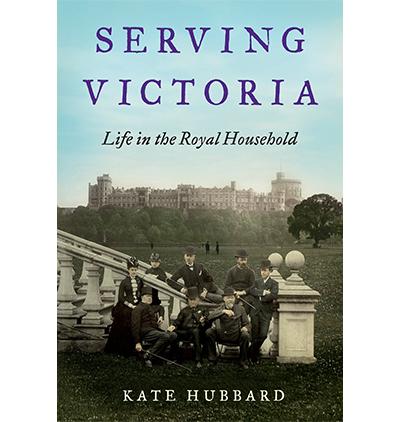

I’ve wanted to read Serving Victoria: Life in the Royal Household for ages as I’m fascinated by Queen Victoria’s court, which seems to have been a hotbed of machination, scheming, petty annoyances and secret affairs. I wasn’t disappointed as Kate Hubbard vividly brings Victoria’s court to life by focusing on the careers of various different courtiers picked from the dozens of ladies in waiting, doctors and chaplains who served the notoriously difficult queen.

I found this book absolutely fascinating – it’s often said that you can really tell what someone is like if you look at the sort of people they surround themselves with and the same is true of Queen Victoria and her household as she wasn’t exactly the sort of person who would tolerate having people that she didn’t like anywhere near her. This was of course somewhat to her detriment when it came to the Ladies of the Bedchamber scandal early on in her career and although she eventually capitulated in that situation, she still insisted upon retaining a firm control on her household throughout her life, preferring to surround herself with handsome young men and pretty amusing women who weren’t fazed by having to navigate the tricky tight rope of appearing both apparently unimpressed by royalty and also properly reverent towards their mistress when she demanded it.

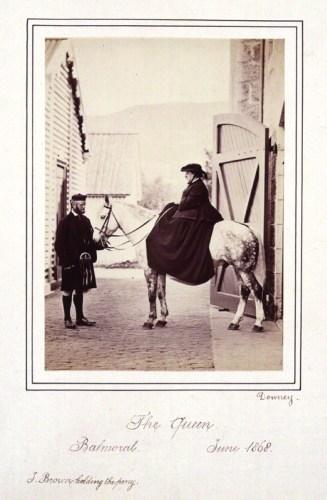

Queen Victoria and John Brown, W. & D. Downey, 1868. Photo: National Portrait Gallery, London.

It’s probably no surprise at all that I could detect quite a few parallels between the household of Queen Victoria and that of her forebear and distant relation Elizabeth I – both women insisted upon absolute loyalty from both men and women, both preferred to surround themselves with good looking, lively, young things, both were in the habit of enjoying the company of handsome men and both were exceedingly put out when their courtiers wanted to get married although they would eventually be grumpily gracious about it when the couple concerned remained unwavering in the face of majestic disapproval. I suppose that Victoria’s household should just have considered themselves fortunate that they didn’t end up in Tower for daring to get engaged.

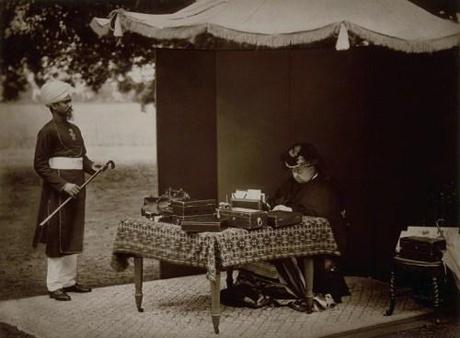

I felt sorry for Victoria’s ladies in waiting though – immured for months on end at Windsor, Osborne or Balmoral, they were effectively cut off from their families during their periods of service and subject to the whims of their mistress. Not that Victoria was an entirely charmless person to work for – she was capable of inspiring great loyalty, had a sense of humour and was always extremely interested in the personal lives of her attendants. However, it wasn’t all good – she could also be exceedingly selfish, intolerant, overly partisan when it came to the faults of her favoured attendants (such as the deeply unpleasant Hafiz Abdul Karim), bad tempered and controlling. I particularly liked the way that she frowned on her immediate household imbibing anything more than a polite amount of alcohol but immediately flew to the defence of any below stairs servants who were caught reeling drunk, arguing that it was just a natural failing of their class and not to be censored. Amazing. I think we’d have got on like a house on fire.

Queen Victoria and Hafiz Abdul Karim, Hills and Saunders, 1893. Photo: National Portrait Gallery, London.

In summary, I really enjoyed this book, which followed the development of the Queen’s household from her accession in 1837 onwards, and found the final chapter, which describes Victoria’s final days very moving, although I was shocked to read that when her personal doctor, Sir James Reid, who had been with her for twenty years, prepared her body for burial, he discovered that she had suffered a cervical prolapse. Poor Victoria.

Queen Victoria, W. & D. Downey, 1872. Photo: National Portrait Gallery, London.

******

‘Frothy, light hearted, gorgeous. The perfect summer read.’ Minette, my young adult novel of 17th century posh doom and intrigue is now £2.02 from Amazon UK and $2.99 from Amazon US.

Blood Sisters, my novel of posh doom and iniquity during the French Revolution is just a fiver (offer is UK only sorry!) right now! Just use the clicky box on my blog sidebar to order your copy!

Follow me on Instagram.