Jamie is a sailmaker; he periodically shares his knowledge on the blog, and those posts are under the Sailmaker tag here. In this first post of a two-part series, he hopes to demystify some of the woo around sailcloth material. Anyone with questions about sails is invited to get in touch; Jamie enjoys sharing from his depth of experience as a sailmaker and a cruiser.

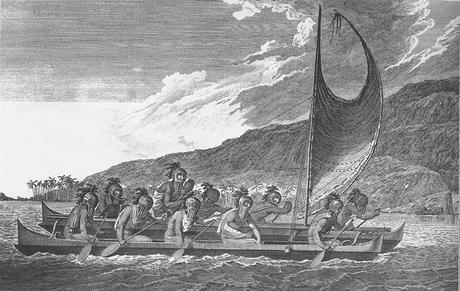

We gifted Totem’s old Dacron mainsail to a family on Ninigo atoll in Papua New Guinea. There, the fatigued sail that pushed and pulled us over thousands of sea miles found a new life as a tarp. Here in Madagascar local dhows use heavy cotton canvas for their sails, but like the Papuans, smaller sailing outriggers make do with tarp material. Often these are rice or flour sacks given a second (third, fourth) life, but otherwise it’s the just cheap plastic, cover the woodpile, hardware store tarp.

Fundamentally these tarps are the same as modern laminate sailcloth: a composite of strong synthetic fibers bound together within a layer of synthetic film. Their tarp sails are monumental leap over traditional hand woven pandanus fiber sails.

Closer to home, natural fiber sailcloth is woven only in old yarns and fading memories. Modern sailcloth is constructed from exotic materials with high tech processes are the way of sailcloth now. Sail-related advertising is often so technically oriented, one wonders if most sailors have chemical engineering degrees! Big yachts with big flashy sails make dazzling photos that prove carbon fibers and chemical wizardry have produced a superior sail.

Great, right – but just as astronauts must understand some of the magic that propels them into space, so to should cruising sailors understand the essence of sails that them over the ocean.

The perfect sailcloth is light as a feather, strong as steel, tough as linebacker and cheap as chips. It doesn’t exist.

Before going geek on sailcloth, here’s a trivia question: the unit of measure for sailcloth is its weight in ounces, say for example, 8 ounce Dacron. What does 8 ounces refer to?

Fibers and Yarns

Fibers are the building blocks of sailcloth. Individual fibers have little strength or weight to speak of, but they’re flexible. Bundle fibers together to form a yarn, which is to a sail is as a steel girder is to a bridge. Fiber types commonly used in sailcloth are so chosen because of specific properties: strength (tenacity), stretch characteristics (modulus of elasticity), shrink rate, UV resistance, and flex fatigue properties.

A challenge to making yarns is getting all of the fibers to an equal tension. When fiber tensions differ, meaning fibers differ in length, shorter one take more load than the longer one. This is one form of “crimp”, that is, compromising strength and stretch integrity due to construction. Another form of crimp is the over-under of yarns in woven sailcloth. As sailcloth is pulled, the over-under yarns pull straighter, causing a change to sail shape. Poor quality yarns and weaving processes make for stretchy sails.

Cloth Construction

Sailcloth is made by either weaving yarns or chemically bonding them with a film layer (and combinations of taffetas and scrims), so-called laminate sailcloth. Each method results in different inherent properties, regardless of fiber type (Dacron, Kevlar, etc.). To help understand this point, we must look to the dynamics of sailcloth in action.

Structurally, sails carry much load, based on sail area, wind strength and relative angle, sail shape and trim, and hull type. These forces mostly follow predictable paths between the corners. Head to clew (leach) has the highest load in a sail. Sail designers orient the strongest yarns in cloth to run parallel to the highest loads. As load angles shift away from parallel to yarns, such as when flogging or with poor sail trim, there are no yarn “girders” so cloth is considerably weaker and stretchier. This is called bias load causing bias stretch.

Applying this to sail geometry is coming in the next post – Sailcloth 102.

This post is syndicated on Sailfeed.