The countdown is over. Tate modern has finally opened its doors for the much awaited, super-hyped and rather smelly retrospective of the most expensive artist of our times, Damien Hirst.

Taking note of what HASN’T been said so far about Hirst it’s probably easier than reminiscing about every bit of comment, or discussion that ever spun out of this complex character. But this is a retrospective; so let’s start at the beginning shall we?

Born in Bristol in 1965, Mr Hirst grew up in Leeds and at 18 years of age, he enrolled at the Jakob Kramen College of Art in the same town. After moving to London, he worked for 2 years in the capital as a builder. Deciding that art was his final call, he then enrolled at Goldsmiths College. There he learned about flamboyant art theories, unlearned all the proper skills on painting and sculpture he might have had (don’t panic, he never had any) and was educated on how to use the finest ‘shock and awe’ techniques in order to make his mark in the art world. What follows next is the stuff of legends. Our hero, together with the other fellow students at Goldsmiths organises a big art show called Freeze. In a disused warehouse in the docklands, Mr Hirst plays the parts of the master of ceremonies, the impresario and the marketing guru all in one, giving the show instant cool and credibility. It’s only a pity that the pieces he actually made for it, were mediocre to say the least. However, for every other artist involved, the exhibition was a success, officially giving birth to what is now known as the YBA’s movement (Young British Artists).

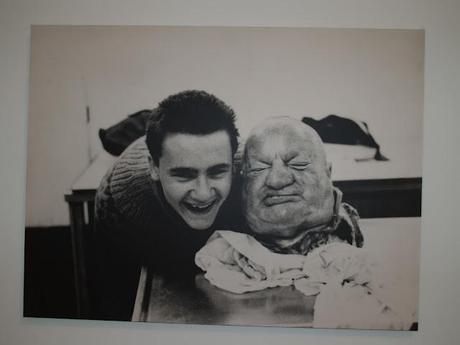

(Damien Hirst at 16 y/o posing next to a cadaver’s head in the Leeds mortuary)

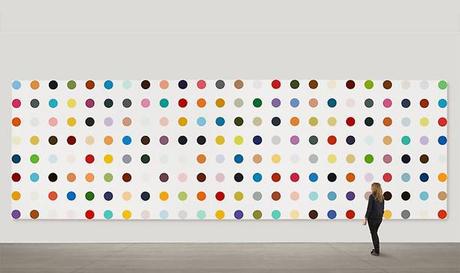

The first room of the retrospective is all about those years. Now who doesn’t remember their time at university with a pang of nostalgia? Those were the times of balancing ping-pong balls on hairdryer’s streams, the years of painting coloured spots on your dorm room’s walls, the years of rearranging pots and pans in the kitchen’s cabinet and filling ashtrays until they exploded. Those were the years in which, when you ran out of weed, you’d have ingested just about anything inside your pharmaceutical cupboard. For instance, our Damien Hirst moment was when me and my flatmates, at Sussex University, left an enormous pile of rubbish to rot in our garden for weeks, developing our very own culture of maggots that would have put good old Damien to shame (we should have framed it and put it in a gallery; we’d have made millions). Anyway that’s exactly what you’re going to find at Tate. All of Hirst’s ideas come from those years. He then proceeded to repeat them to death and create such a big hype about himself and his work, that every other person, who had more money than sense, felt compelled to buy into it. Moving on, and picking up the pieces that marked a turning point in his career, one realises that there’s no point in going through his entire body of work. It’s all the same. Spot paintings (which, famously, he doesn’t even do himself), pharmaceutical cabinets (Damien I advise you take some of the stuff inside the cupboards, you might actually get some good ideas for your next show) and rotting meat. In my humble opinion, his best piece to date is also the one he did immediately after Freeze. ‘A Thousand Years’ is made out of 2 cabinets representing the circle of life, in one box we have hatching maggots turning into flies, who then move into a second cabinet, where they find a severed cow’s head in a congealed pool of blood. The flies are born, feast, live and love in and around this space, ultimately finding their demise on a neon light (the ‘insecticutor’ has been redubbed) located in the second cabinet, just above the cow’s head.

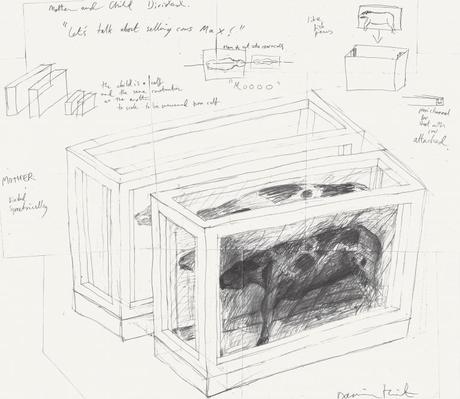

(A thousand years)

This is probably the only real piece of art of the whole show (and Hirst’s career) and starting with this one, he probably didn’t do himself a favour. In fact ‘A Thousand Years’ feels more like the finishing point of an artist’s career than the starting one. Nevertheless it encapsulates everything that Hirst could have been. The smell is unbelievable (probably as strong as the imagery), one can’t resist the fascination of looking on how the insects are electrocuted by the dozen and let’s face it, who wouldn’t be captured by a severed cow’s head lying in a pool of blood. The allegory to the human condition is strong and the casualty, with which the ‘insecticutor’ strikes, resembles too much the casualty of our own deaths. Apparently the piece it’s full of references to Hirst’s most loved artists, Bruce Nauman for the neon, Naum Gabo for the spatial elements, Sol Lewit for the cube and Francis Bacon for the cow’s head.

It is said that when Bacon saw it the first time, he was mesmerized by it, declaring that Hirst had finally created what he had tried to put on canvas for 40 years and identifying him as his natural successor. If only young Damien would have kept the standards to that level, we’d probably be talking about the greatest artist who ever lived and not the richest one, but alas that wasn’t to be. The same happens for ‘In and Out of Love’ where the life cycle this time is recreated with the help of some butterflies and the added elements of canvases hanging on the walls and stale fruit bowls lying on a table.

(In and out of Love)

The fruit bowls, over time, develop high levels of alcohol making every insect feeding on them drunk and ultimately killing it. The visual elements are definitely more pleasing to the eye compared to the flies and the severed cow’s head and death is sweeter for the butterflies than ever was for the flies, but for those same reasons the artwork loses punch and it becomes just a butterfly house, which would make every kid in the country happy, but that doesn’t really cut it in the holy temple of modern art. The next piece is ‘Mother and Child Divided’, the one that awarded Damien the Turner price in 1995 (against a very feeble opposition must be said). Like the best advertisers in the business, good old Damien plays on the title by creating a visual pun, the mother and child (a cow and a calf) have literally been cut in half (divided) with a chainsaw and then put into separate tanks of formaldehyde.

(Original Sketch of ‘Mother and Child Divided, made by Hirst in 1993)

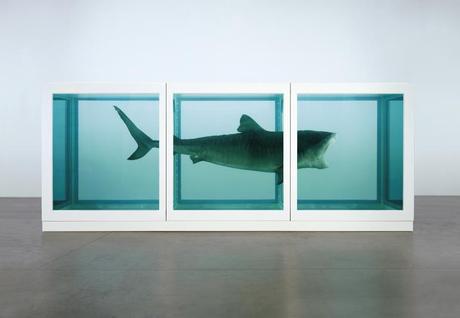

Shock factor aside (it would have made Jason from Friday the 13th proud) there’s not much to be said about this one, except that he probably developed excellent butchering skills by dismembering it and putting it back together. For anyone who wants to be shocked and is into this sort of stuff (dead animals’ bodies in formaldehyde) I advise a walk to the Royal Surgeon Museum in Lincoln’s Inn fields, ‘Mother and Child Divided’ will feel like a tickle on the belly after that and you might actually get to learn something. Moving on we meet the infamous shark, which is actually called ‘The Physical Impossibility of Death in The Mind of Someone Living’.

(The Physical Impossibility of Death in The Mind of Someone Living)

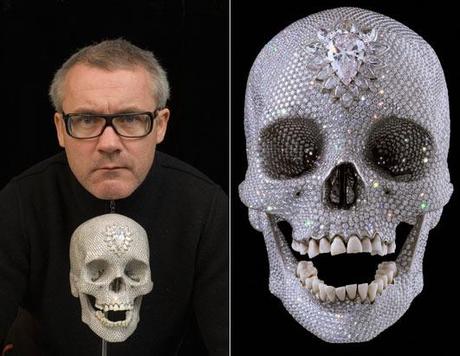

Ridiculously pretentious title aside, I don’t know what to say about this one. Go to the Natural History Museum, if this is the sort of stuff you’re after, they even have a whale over there and a whole other bunch of stuffed animals. Legend has it that Charles Saatchi had a lot to do with this piece, which makes it even worse. Not for Damien not owning up to its creativity, but because you’d expect Saatchi to have a little bit more brain than that. However these were his most flamboyant years so he might be forgiven. It’s also known that Hirst worked out the costs and details on beer mats and pub receipts, so probably it all started during a one-too-many drinking session and it all ended with them working on this massive hangover of a project. Again the only thing worth mentioning is the ‘shock and awe’ technique that would have put to shame the most seasoned army general. After the ‘rotting meat’ period, comes the ‘more money than God’ period. Damien had made it, thanks to a constant stream of spot paintings, sharks in formaldehyde, cigarette butts, butterflies and medicine cabinets (all produced by his assistants. He was too busy living the high life and pushing his art on the likes of Kate Moss, Ronnie O’Sullivan, Ronnie Wood etc. to actually produce any work himself), he had made so much money that it all became abstract to him (the money, not the art). Tormented by the millions he had made, he decided to splash out on what he said at the time was his masterpiece. ‘For The Love of God’ is the piece that ends the retrospective. Housed in a vault in the big turbine hall and constantly guarded by a security team, it provides the final farcical act to this comedy of a retrospective; the final triumph of bad taste.

(For the Love of God)

This human skull encrusted with a ridiculous amount of flawless diamonds (8,601 to be precise), really epitomises what Hirst has become, a mediocre artist. It is suppose to explore how the artist used his acquired wealth as art material, but, in truth, it is just the final, most refined example, of that technique he has championed over the years, providing all style and no substance. So what’s next for our hero? Analysing his journey he has really come full circle. There’s nothing in today’s Damien Hirst that resembles the artist of the beginnings. He was poor then and super rich now, he once declared that he would never trust somebody who didn’t smoke and is completely and utterly against it now (having quit some years ago), even the last taboo of him refusing to do any retrospective has been broken with this show (he said they were for dead people). I’d like to believe that with this retrospective we will also find closure on his bad art, but I am afraid it won’t be so. Some people (namely himself) said that he has been greatly misunderstood, but that’s fine, because also Picasso and Warhol were heavily criticised in their times, and I think he’s right to associate himself with those artists. He does remind me of the worst Warhol (the one after the attempt on his life, when he became a total sell out) or the last Picasso (after he had passed on the baton of innovation). Maybe the best lesson he learned from these two titans is how to make a mint from your art while you’re still alive, but I wouldn’t compare them just yet. So what’s the final judgment on the artist? Is he one of the all-time greatest? Or just another one of the many vacant conceptual artists that crowd today’s galleries? Is his work going to resonate forever in human history? Or will he be forgotten as soon as a new sensation comes along? The debate is open on Mr Hirst (and will be for some time), but I want to conclude with one last story. Charles Saatchi once said that in a hundred years, when the art history books will have to be mercilessly selective in editing last century’s art, only three names will make the team; Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol and Damien Hirst (Picasso was born in 1881). True or false? Hero or villain? Connect the spots (paintings) and you’ll find out.

Post edited by guest blogger Carlo Formisano