Watching Steven Spielberg's The BFG as an adult is the cinematic equivalent of reading a cute, but somewhat unremarkable bedtime story to your child (or niece or nephew or whatever). It's an agreeable enough experience, and you appreciate the basic, but necessary lessons the child is supposed to learn through the story. You might even admire the way the author weaved that in there. By the end of the book, you think, "Well, that was cute," and, if you're lucky, you put the child to bed. In that sense, the book did its job, but you weren't exactly taken on a magical journey. The cutesy narrative, singsongy language and pleasant illustrations amused you without completely grabbing you in a meaningful way.

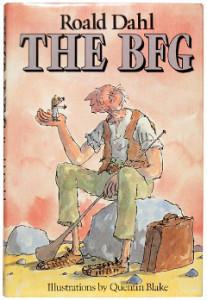

Is that really a bad thing, though? After all, The BFG is adapted from Roald Dahl's 1982 novel of the same name, which regularly ranks somewhere in the top 100 in any list of best children's novels.

Kind of. It definitely means they dutifully brought the story to life, but their recreation, starring Mark Rylance (aka, t he best part of Spielberg's Bridge of Spies) as the titular Big Friendly Giant and newcomer Ruby Barnhill (very promising, if sometimes a bit challenged to pretend she's acting against something other than green screen) as his new ward Sophie, somehow lacks the magic which made the novel so beloved in the first place. Theirs is a movie full of magical moments which don't quite add up in the end.

But let's start at the beginning, which is when The BFG is at its best. We meet Sophie as she narrates her late night actions in a mid-80s British orphanage, using a blanket to conceal herself as she trails the largely unseen headmistress who repeatedly shirks her responsibilities. While the rest of the children sleep, it is Sophie who has to collect and sort the mail. She's the one who makes sure the front door is locked, and that drunkards down the street don't wake up the kids with their nonsense. Sophie more or less runs the place, yet she still lives in fear of the headmistress, whose domineering shadow looms large over the sleeping children the one time she opens the door to the shared bedroom to check in on them.

Clearly, this is a story being told from a child's point of view, and as beautifully realized through Spielberg's use of shadows it's obvious that to Sophie the headmistress seems like a big unfriendly giant. What better time, then, to meet a big friendly giant?

Their initial meeting is almost dreamlike. In response to a strange noise outside, Sophie approaches the gorgeous double doors leading to the orphanage's balcony, and her every step forward bathes her in a gorgeous blue light, as the streetlights filter through the curtains. However, it quickly turns into a nightmare when she sees the source of the noise is a giant, building-sized man. Try as she might to hide from him by running back to her bed she can't escape his giant hand when it reaches through the doors to snatch her away.

This is a genuinely scary scene, but it's immediately followed up by cinematic joy, with the type of imagery Doahl and his animators simply couldn't do on the page. We watch as the BFG makes his way out of the town, using all matter of inventive tricks (e.g., covering a street lamp, crouching on the back of a truck) to conceal his appearance whenever anyone should happen to drive/walk by at such an ungodly hour. The John Williams score accentuates the playfulness of these moments before swelling to suggest wonder and majesty when the BFG is finally out of town and in the woods. He towers over nature, literally jumping from one mountain to the next, running so fast the tallest trees sway like leaves in the wind.

Once they cross over into giant territory, presented as a secret land accessible only through the clouds above the tallest mountain, the film quite suddenly loses its considerable momentum. For one thing, by the time the BFG is back in his rather humble cabin and conversing with Sophie (he means her no harm, but had to take her for fear that she'd tell everyone about him) there is a definite period of adjustment for your eyes. Everything looks just a bit off, from the size differential between the BFG and Sophie to the animation on the BFG's face to highlight Mark Rylance's rather pronounced expressions.

You similarly have to adjust to Rylance's voice, specifically the broken English employed by the BFG. He has learned how to read and is smarter than the average giant, but his sentences often turn into a barrage of bumbled words. He knows what he's trying to say, but you (and Sophie as well, obviously) have to learn that, for example, when he says, "Is I right, or Is I left?' he means, "Am I correct?"

Once you've adjusted to all of that you can meet the film on its terms, and appreciate the unfolding narrative and its inherent lesson about bullying (the other giants, led by one voiced by Jemaine Clement, all pick on ole poor BFG). You can delight in the magical imagery when the BFG takes Sophie with him to collect dreams, floating in the air like little color-coded energy balls (shades of Inside Out). There is a truly wonderful sequence of the BFG and Sophie going back into town together and delivering these captured dreams to an entire family, with Spielberg again using shadows to great effect.

However, in other areas the story is sadly lacking:

- Sophie goes from wanting to run away from The BFG to never wanting to leave him just a bit too quickly. There's a fantastic montage to be had of these two growing closer, but it's not here.

- Too much of the story's darker edges have been sanded off. The conflict turns into Sophie and the BFG versus the other giants who steal and eat little kids every night, yet outside of one dream sequence (and newspaper headline) that's left mostly to our imagination. I get wanting to keep this family friendly, but this absence makes the story far more about bullying and less about, "Oh, yeah, these dudes are eating little kids. We have to stop them."

- The final act invades the real world in a way which feels of a completely different tone from the rest of the film, although this is the section of the story with the best jokes.

- Sophie is gifted a new parental figure in truly abrupt fashion.

By the end, you walk out of the theater, John Williams' very Williams-y score playing behind you, and you wonder, "Why didn't I like that more?" You flash to all of the little things the story could have done better, but before long you'll also flash to that opening sequence or that part around the magic tree, the orphan and her new, big friend literally chasing dreams. You'll also laugh about all those whizzpoppers. You'll realize that if Spielberg's BFG were a book it wouldn't be the one you most want to read to your kids, but when they ask for it you won't mind reading it to them again.

THE BOTTOM LINEThere are far worse things than sitting down and listening to Grandpa Spielberg tell us a fairly entertaining bedtime story. "Grandpa, you're older stories seemed a little better, a little more magical," we'll say, before looking up at his soulful face (or, in this case, at the soulful face of Mark Rylance) and concluding, "But this one's not so bad."

ROTTENTOMATOES CONSENSUS73% - " The BFG minimizes the darker elements of Roald Dahl's classic in favor of a resolutely good-natured, visually stunning, and largely successful family-friendly adventure."