Life comes from the "it's like x meets x" school of moviemaking, whereby you take two different, but well-known movies and merge them together to create something newish. It's the line used over and over again by writers, directors and producers in film studio pitch meetings, giving the money people both a better idea of what they're being asked to pay for and how easy the resulting film might be to market. Thus, at some point in Life's infancy there was undoubtedly a moment where someone excitedly proclaimed "it's like Gravity meets Alien."

The plot, as so easily communicated in the various trailers, is instantly familiar: people in space encounter new alien life which quickly turns hostile. Cue a slasher-like progression of death scenes, and next thing you know the movie's over.

To be more specific, a multinational six-member crew (who all have little flags on their shoulders to make it easier for us to tell where everyone is from) of an international space station are sent to retrieve sand samples from Mars and study them in isolation in space. In so doing, they discover a microscopic organism which doesn't stay microscopic for very long, and, well, you remember how the aliens in Arrival were refreshingly benevolent? Yeah, not so much in Life. A lab mishap harms the alien, and it eventually lashes out in self-defense, growing from nothing to something resembling an octopus to something more resembling a scary devil rey. Carnage ensues.

The only thing new about this set-up is the attempt to marry the somewhat more grounded-in-reality approach of Gravity and Interstellar with the B-movie thrills of Alien and its countless imitators. Thus, Life opens with an extended Steadicam one-shot (minus some judiciously employed invisible cuts) of the crew working in perfect harmony, with brash mechanic Ryan Reynolds out on a spacewalk to capture the wayward sample container they were sent to retrieve while everyone else coordinates their actions in the station under the captain's orders, decisively floating from point to point and manning their respective stations. The situation is different, but the feel and overall effect unmistakably invokes Gravity.

Still, in this context it's a thrilling opening as well as an efficient introduction to every single character and what role they serve. Katerina (Olga Dihovichnaya) is the French commander, David (Jake Gyllenhaal) the American medical officer, Miranda (Rebecca Ferguson) the British quarantine officer, Sho (Hiroyuki Sanada) the Japanese pilot and Hugh (Ariyon Bakare) the British biologist. Plus, obviously, there's Ryan Reynold's character Roy, who proudly yells "Instagram that shit!" after preventing the sample container from floating into deep space, thus inspiring his buddy Hugh to take a polaroid picture since that's their best version of Instagram.

And then everyone dies.

Okay. It doesn't quite happen that quickly. We have to spend some time with these people, get to know them, quickly decide who to root for (awww, the nice biologist is paralyzed from the waist down, and hopes the study of alien life might reveal cures for human diseases and ailments) and who to regard as dead meat. The film's chief strength is the way it keeps us guessing as to who might survive and who might not. Assumptions make based on name recognition are quickly challenged.

But what's the point of it all? What big idea is Life attempting to explore?

Nothing. There is nothing more to this movie than sheer set-up for tension and survival horror. The potential multinational angle of "we can work together as people from different lands to defeat this thing" is left unused. The film lacks the "what's the meaning of life?" navel-gazing of 2001, Mission to Mars, Prometheus and Interstellar, the mickfuckery of Event Horizon, the symbolic sentiment of Gravity, process-oriented fun of The Martian or even the anti-corporation stance and staunch feminism of Alien. Instead, it's an artsier slasher movie in space, unencumbered by outsized ambition and simply aiming to deliver genre thrills as efficiently as possible.

Movies like this don't get made as often as they used to because why listen to a pitch for "it's like Gravity meets Alien" when you can simply go make another Alien sequel/prequel. In a couple of months, Life will have receded from people's memories, and we'll be talking about Alien: Covenant. But at least the people behind Life tried to make something familiar, but also kind of new. Whether or not you can shake the familiarity of it all might depend on just how many "trapped in space" movies you've seen.

THE BOTTOM LINEDespite the credible work put in by Reynolds, Gyllenhaal, Ferguson and the rest, Life's primary purpose is simply to find new ways to kill characters in space. For example, you try spacewalking while toxic coolant slowly floats into your helmet from another part of your suit, progressively blinding you and cutting off your air. It doesn't sound fun, but it's sure fun to watch, just as long as you don't expect much more than a B-movie version of Gravity meets Alien.

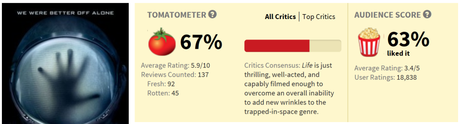

ROTTENTOMATOES CONSEUS

Life is the first big budget film from long time indie producers Bonnie Curtis and Julie Lynn, who were previously best known for character-driven movies like Albert Nobbs and Last Days in the Desert. Skydance Media raised the majority of Life's $60 million budget and entrusted Curtis and Lynn with figuring out how best to spend all the money. Their solution, as they recently told The Frame, was to hire Gravity, Interstellar and The Martian vets to helm the crew, and take advantage of all the "how to make an outer space movie" lessons those technical experts had learned. At the suggestion of one such expert, an assistant director to be exact, they employed two full, independent crews simultaneously throughout production because the wirework involved in filming zero gravity scene is so tedious it leads to hours of downtime/set-up. With two crews, though, the director Daniel Espinosa was able to go back and forth and shoot twice as much in a day.

Plus, Curtis and Lynn did away with mandatory lunch hours and kept to a rigid schedule of working continuously from 8 AM to 6 PM and then releasing everyone to go home to their families in the evening. Lunch, of course, was made available during standard lunch hours. Everyone was free to stop and eat when they needed to. However, the entire production did not have to screech to a halt to allow that to happen. Such a policy might seem like it would fly in the face of union rules, but they somehow managed to make it work and ultimately shaved days off the shooting schedule and came in under budget ($58m).