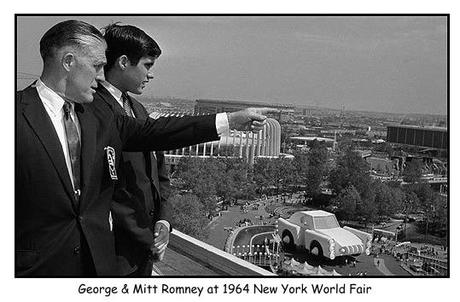

It is no secret that Mitt Romney -- this week's Iowa Caucus winner and now clear frontrunner for the Republican 2012 presidential nomination -- is not the first member of his family to seek the White House. Mitt's father, three-term Michigan governor George W. Romney, also made the attempt back in 1968. Mitt was just 21 years old at the time, and his father came achingly close before seeing his campaign for the Republican ticket collapse over a classic verbal gaffe -- telling reporters he had been "brainwashed" by Pentagon officials into supporting the Vietnam war. But more on that later.

It is no secret that Mitt Romney -- this week's Iowa Caucus winner and now clear frontrunner for the Republican 2012 presidential nomination -- is not the first member of his family to seek the White House. Mitt's father, three-term Michigan governor George W. Romney, also made the attempt back in 1968. Mitt was just 21 years old at the time, and his father came achingly close before seeing his campaign for the Republican ticket collapse over a classic verbal gaffe -- telling reporters he had been "brainwashed" by Pentagon officials into supporting the Vietnam war. But more on that later.

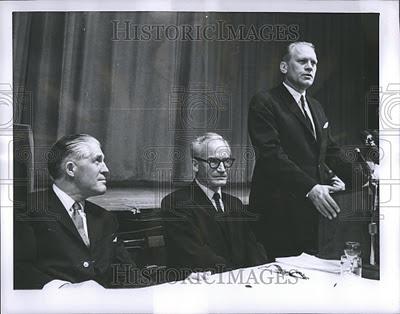

Then-Michigan Gov. George Romney (father of now-presidential

candidate Mitt Romney), seated in 1964 with then-Republican presidential

candidate Barry Goldwater, whom Romney refused to enforse and called

an "extremist." At the podium is future president Gerald Ford, then still

a Congressman from Michigan.

Today's 2012 Republican presidential contest has much in common with 1964. Then as now, conservative activists had launched a strident revolt against what they considered a "moderate" party elite.

Today, the two sides are personified by Mitt Romney, the more moderate, versus several competing conservative "anti-Romneys" -- Newt Gingrich, Santorum, Rick Perry, and Ron Paul, and the rest. Back in 1964, these two sides were led by Goldwater on the right and, for the moderates, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller. George Romney stood shoulder-to-shoulder with Rockefeller.

Barry Goldwater, a World War II Air Force pilot, two-term US Senator, and author of The Conscience of a Conservative, happily represented the far right. He saved his sharpest elbows for eastern moderates in his own Party. "[S]ometimes I think this country would be better off if we could just saw off the Eastern Seaboard and let it float out to sea," he once told reporters in 1961. As for Russian communists, he joked that the U.S. military should just "lob one [nuclear bomb] into the men's room of the Kremlin" and solve the problem for good.

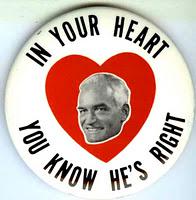

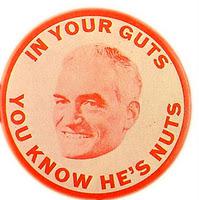

Goldwater voted against the 1964 Civil Rights Act which, in the heat of 1964, drew major attention in the South. He denied being racist, but when asked to renounce prejudice in a formal way, he refused. "In your heart you know he's right," chanted friends. Enemies replied: "In your guts, you know he's nuts."

Nelson and Happy Rockefeller on their 1963 honeymoon.

Nelson Rockefeller, by contrast, oozed with eastern elitism. The wealthy grandson of Standard Oil titan John D. Rockefeller, the New York governor not only practiced liberal big-city politics but also crossed a cultural taboo in 1963 by divorcing his wife and immediately marrying a women fifteen years younger named Happy who also had recently divorced her own husband and ceded him custody of their four children. Few doubted that the two had a secret affair for years. In 1964, adultury still mattered.Barry Goldwater and Nelson Rockefeller fought a string of bitter primary contests in early 1964, but Goldwater's triumph in California gave him by far the most delegates. When the Party met for its nominating convention at the Cow Palace in San Francisco, tension boiled. A last-ditch stop-Goldwater effort quickly materialized. Leading it was George W. Romney.

George Romney had been elected Michigan governor in 1962. A former auto executive, he had created a state income tax and, like Rockefeller, was a strong civil rights backer. In June 1964, watching the growing split in his Party, Romney had no trouble picking sides. He joined 12 other Republican governors that month in blasting Goldwater, declaring "I will do everything within my power to keep him from becoming the party's presidential nominee." Reaching the convention in San Francisco, he told the platform committee to "unequivocally reject extremism of the right and the left" -- a clear slap at Goldwater and his followers.

Charges of "extremism" against Goldwater crescendoed over the next few days, culminating in a ugly scene as Nelson Rockefeller himself was loudly booed when he addressed the convention in a confrontational speech (see clip above). Eight different candidates received first ballot votes (including 41 for Romney), but this was not enough to stop the inevitable. In accepting the nomination, Goldwater shot back at his critics: "I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice. And let me remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue."

After San Francisco, Republican moderates abandoned the party in droves. Still, Barry Goldwater still hoped he might be able to win over George Romney. He reached out, and Romney apparently was willing to try to bridge the gap. That August, just prior to a meeting in Pennsylvania, Romney sent Goldwater (via his vice presidential running mate Congressman William Miller (R-NY)) a brief statement on civil rights and asked Goldwater to endorse it as a way to de-fuse the issue. According to journalists Roland Evans and Robert Novak, the statement read in part as follows: "The rights of some must not be enjoyed by denying the rights of others. Neither can we permit states rights at the expense of human rights."

Goldwater refused, and after that George Romney drew the line. He refused to endorse Goldwater or to appear with him publicly. Later, he wrote Goldwater a twelve page private letter explaining his reasons, focusing on civil rights In the end, Romney won re-election that year as Michigan governor by 380,000 votes as Goldwater was losing the state by over a million.

All of which brings us back to Mitt Romney and 2012. Talking a few years ago to Tim Russert about his father (who died in 1995), Mitt described the 1964 confrontation in these terms: “my dad walked out of the Republican convention in 1964 in San Francisco in part because Barry Goldwater in his speech gave my dad the impression that he was someone who would be weak on civil rights.”

As Mitt Romney today prepares to fight the conservative wing of his modern Republican Party in a contest not much different from the Goldwater insurgency of 1964, will Mitt have the same backbone as his father to stand up for his "moderate" beliefs, even at the cost of catcalls and boos from the right wing chorus? Stay tuned.....

In Part II, we'll talk about that "brainwashing" episode. I think you'll be surprised at the truth.....