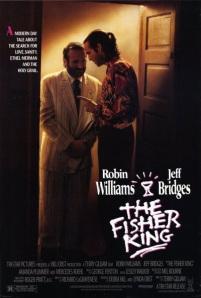

THE FISHER KING

The Fisher King, in which Robin Williams plays a homeless man whose life as an academic had been destroyed by the trauma of witnessing his wife’s brutal murder. The role may well have been one of Williams’s greatest and most-challenging performance.

“The Fisher King” stars Jeff Bridges as Jack, a radio talk show host. It begins stunningly well with a few glimpses of Jack Lucas (Mr. Bridges), a sleek, mean-spirited radio bully who is quite literally on top of the world. As the shock-radio DJ, Bridges has a malignant hatred of people. He insults his listeners daily, then he gets stoned in a black, glass tower of a penthouse while listening to the anthemic song “The Power.” Seen in his fashionably dehumanized high-rise apartment, or in his limousine, sneering at a pan-handler from behind dark glasses, Jack is instantly emblematic of the cold-hearted excesses of his time.

When Jack is next seen, three years later, he is as demoralized and barren as the mythical figure for whom the film is named. He now looks disheveled and lives listlessly with girlfriend and video store owner Anne Napolitano (Mercedes Ruehl), who has clearly not been successful in rekindling his spirits. One night while on a bender, he attempts suicide. Before he can do so, he is mistaken for a homeless person and is attacked and nearly set on fire by thugs.

But Jack’s quest for real forgiveness has just begun. His redemption arrrives in the

Wearing Parry’s clothing, Jack infiltrates the Upper East Side castle of a famous architect and retrieves what Parry believed was the Holy Grail, in reality a simple trophy which Parry had seen inside the house. When he brings it to Parry, the catatonia is broken and Parry regains consciousness. Lydia comes to visit Parry as usual in the hospital. She finds that Parry is awake and hears him and Jack leading the patients of the mental ward in a rousing rendition of “How About You?.” Jack goes back to the video store and tells Anne that he loves her.

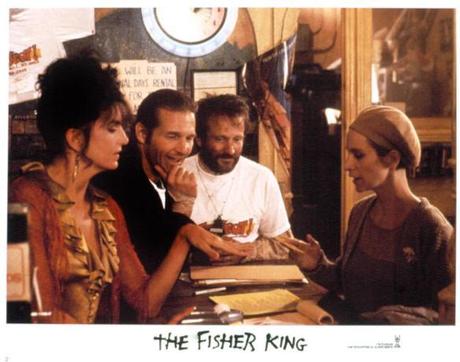

“The Fisher King,” directed by the ever-fanciful Terry Gilliam from an ingenious if loose-knit screenplay by Richard LaGravenese, is capable of great charm whenever its taste for chaos is kept in check. For every wild ride through Manhattan by an imaginary Red Knight trailing billows of flame, there is a small, comic encounter in a more down-to-earth mode.

The Red Knight, as well as the expressive set pieces of New York’s post-crackdown, pre-Giuliani homeless jungle, offer familiar sights to Terry Gilliam fans expecting his fantastical direction. The film even offers references to some of his other work, most explicitly Monty Python and the Holy Grail and Brazil — a Brazil poster dots the wall of the Video Spot office, and high angle shots of Lydia’s bureaucratic publishing job recall the stifling morass of office life in the director’s masterpiece. Gilliam gets magnificent performances from all four of his leads. Alight approach floats the film through potential pitfalls, such as its wafer-thin view of homelessness in post-Reagan America. The two most prominent homeless people in the film, Parry and a cabaret queen played by Michael Jeter, both found themselves crazed and homeless not because of deep-rooted psychological issues or economic duress but because of major traumas that broke them.

Compare this plainer, more realistic view of romance and romanticism to the lofty, self-consuming varieties found in Brazil, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, even, to an extent, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Though that style creeps in with the vignettes involving the Red Knight, The Fisher King deals in lilting but painfully tangible visions of love. Parry’s reverie in Grand Central Terminal turns the place into a giant dance hall, but beneath the gorgeous image of the expansive transit station bathed in angelic light is the harsh sight of the ragged Parry chasing a love that keeps getting farther away. When he finally gets to confess his feelings for Lydia, he must first overcome the uneasy suggestion that he’s a stalker. There’s a thin line between love at first sight and obsession, but Williams manages to find himself on the right side of the divide with a gorgeous speech that turns his microscopic detail of her life into a love letter. Insecure but harmless people like Parry cannot just ask someone out: they have to get to know the person and learn her quirks and likes and worries first.

The Fisher King may stands as the most touching movie Terry Gilliam, the director ever made, among his many masterpieces.