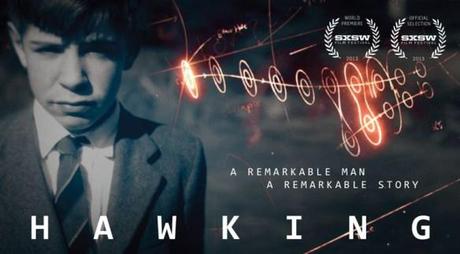

Hawking is the extraordinary story of the planet’s most famous living scientist, told for the first time in his own words and by those closest to him. Made with unique access to Hawking’s private life, this is an intimate and moving journey into Stephen’s world, both past and present. Hawking relates his incredible personal journey from boyhood underachiever, to Ph.D. genius, to being diagnosed with ALS (or Lou Gehrig’s disease) and given just two years to live.

Despite the constant threat of death, Hawking makes amazing scientific discoveries and rises to fame and superstardom.

He tells us about his childhood and his Oxford student days, when his illness was diagnosed; about his first marriage; about his students; about his science. We see him in daily tasks like eating, assisted by caretakers patiently lifting food to his misshapen, passive face.

Among several interesting vignettes from the film about his life are a few of the following.

1. “I was close to death after bout of pneumonia in 1980s. I was rushed to hospital and put on a ventilator. The doctor said they thought I was so far gone they offered to turn off the ventilator.”

Stephen Hawking tells the Royal College of Surgeons about his near-death experience following pneumonia.

Stephen Hawking had a tube inserted into his windpipe 30 years ago after he had developed motor neuron disease. The physicist, once became very ill during a bout of pneumonia during the 1980s while visiting Switzerland. He was considered to be “so far gone” that medics weighed up disconnecting his ventilator. Doctors later agreed Hawking, should be flown back from Switzerland, to England for further treatment. There he was able to lead close to a full and active life. The 72-year-old told the Royal College of Surgeons: “I was rushed to hospital and put on a ventilator. The doctor said they thought I was so far gone they offered to turn off the ventilator. But I was flown back to Cambridge. The doctors there tried hard to get me back to how I was before.” He was speaking at the launch of the European Global Tracheostomy Collaborative (GTC) in central London, where he was given a standing ovation by more than 200 delegates. He said: “For the last three years I have been on full-time ventilation but this has not prevented me from leading a full and active life.“

Stephen Hawking dismisses belief in God in an exclusive interview with the Guardian.

2. “We should seek the greatest value of our action.” “There is no heaven; it’s a fairy story. I think the conventional afterlife is a fairy tale for people afraid of the dark.” He rejected the notion of life beyond death and emphasized the need to fulfill our potential on Earth by making good use of our lives. He says there was nothing beyond the moment when the brain flickers for the final time.”I regard the brain as a computer which will stop working when its components fail. There is no heaven or afterlife for broken down computers; that is a fairy story for people afraid of the dark“. Hawking’s comments go beyond those laid out in his 2010 book, The Grand Design, in which he asserted that there is no need for a creator to explain the existence of the universe. The book provoked a backlash from some religious leaders, including the chief rabbi, Lord Sacks, who accused Hawking of committing an “elementary fallacy” of logic. The physicist’s remarks draw a stark line between the use of God as a metaphor and the belief in an omniscient creator whose hands guide the workings of the cosmos.

3. ” It’s theoretically possible to copy the brain on to a computer,..”

Theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking with his sister Mary at the premiere of the documentary Hawking in Cambridge.

Stephen Hawking said he believes brains could exist independently of the body, but that the idea of a conventional afterlife is a fairy tale. Speaking at the premiere of a documentary film about his life, the theoretical physicist said: “I think the brain is like a program in the mind, which is like a computer, so it’s theoretically possible to copy the brain on to a computer and so provide a form of life after death. “However, this is way beyond our present capabilities. I think the conventional afterlife is a fairy tale for people afraid of the dark.”

4. “All my life I have lived with the threat of an early death, so I hate wasting time.” The incurable illness was expected to kill Hawking within a few years of its symptoms arising, an outlook that turned the young scientist to Wagner, but ultimately led him to enjoy life more, he has said, despite the cloud hanging over his future. The 71-year-old physicist also backs the right for the terminally ill to end their lives as long as safeguards were in place, was diagnosed with motor neurone disease at the age of 21 and given two to three years to live.