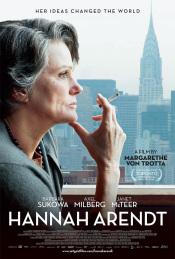

A look at the life of philosopher and political theorist Hannah Arendt, who reported for The New Yorker on the war crimes trial of the Nazi Adolf Eichmann.

A look at the life of philosopher and political theorist Hannah Arendt, who reported for The New Yorker on the war crimes trial of the Nazi Adolf Eichmann.

Arendt’s reporting on the 1961 trial of ex-Nazi Adolf Eichmann in The New Yorker—controversial both for her portrayal of Eichmann and the Jewish councils—introduced her now-famous concept of the “Banality of Evil.” Using footage from the actual Eichmann trial and weaving a narrative that spans three countries, von Trotta beautifully turns the often invisible passion for thought into immersive, dramatic cinema. An Official Selection at the Toronto International and New York Jewish Film Festivals, Hannah Arendt also co-stars Klaus Pohl as philosopher Martin Heidegger, Nicolas Woodeson as New Yorker editor William Shawn, and two-time Oscar Nominee Janet McTeer (Albert Nobbs) as novelist Mary McCarthy.http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KDO5u2YSbm0

Arendt’s reporting on the 1961 trial of ex-Nazi Adolf Eichmann in The New Yorker—controversial both for her portrayal of Eichmann and the Jewish councils—introduced her now-famous concept of the “Banality of Evil.” Using footage from the actual Eichmann trial and weaving a narrative that spans three countries, von Trotta beautifully turns the often invisible passion for thought into immersive, dramatic cinema. An Official Selection at the Toronto International and New York Jewish Film Festivals, Hannah Arendt also co-stars Klaus Pohl as philosopher Martin Heidegger, Nicolas Woodeson as New Yorker editor William Shawn, and two-time Oscar Nominee Janet McTeer (Albert Nobbs) as novelist Mary McCarthy.http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KDO5u2YSbm0

The banality of evil is examined in this solid and intelligent account of Arendt’s controversial conclusions on the trial of Adolf Eichmann. Deftly blending low-key drama with archival black-and-white footage of the Nazi’s cross-examination, director Margarethe von Trotta raises thorny questions about complicity and guilt, conclusions which caused outrage when first aired in the pages of the New Yorker. Award-winner Barbara Sukowa is excellently measured in the title role. “Hannah Arendt,” has unleashed emotional commentary that mirrors the fierce debate Arendt herself ignited over half a century ago, when she covered the trial of the notorious war criminal Adolf Eichmann. One of the pre-eminent political thinkers of the 20th century, Arendt, who died in 1975 at the age of 69, was a Jew arrested by the German police in 1933, forced into exile and later imprisoned in an internment camp. She escaped and fled to the United States in 1941, where she wrote the seminal books “The Origins of Totalitarianism” and “The Human Condition.”Adolf Eichmann was living among a fraternity of former Nazis in Argentina, before Israeli agents captured him and spirited him out of the country and to Israel for trial. When Arendt heard that Eichmann was to be put on trial, she knew she had to attend. It would be, she wrote, her last opportunity to see a major Nazi “in the flesh.” Adolf Eichmann in the Jerusalem courtroom where he was tried in 1961 for war crimes committed during World War II.Eichmann’s writings include an unpublished memoir, “The Others Spoke, Now Will I Speak,” and an interview conducted over many months with a Nazi journalist and war criminal, Willem Sassen, which were not released until long after the trial. Eichmann’s justification of his actions to Sassen is considered more genuine than his testimony before judges in Jerusalem.Writing in The New Yorker, she expressed shock that Eichmann was not a monster, but “terribly and terrifyingly normal.” Her reports for the magazine were compiled into a book, “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil,” published in 1963.Arendt famously insisted that Eichmann “had no motives at all” and that he “never realized what he was doing.” That evil, Arendt argued, originates in the neediness of lonely, alienated bourgeois people who live lives so devoid of higher meaning that they give themselves fully to movements. It is the meaning Eichmann finds as part of the Nazi movement that leads him to do anything and sacrifice everything. Such joiners are not stupid; they are not robots. But they are thoughtless in the sense that they abandon their independence, their capacity to think for themselves, and instead commit themselves absolutely to the fictional truth of the movement.Arendt’s insisted we see Eichmann as a terrifyingly normal “déclassé son of a solid middle-class family” who was radicalized by an idealistic anti-state movement.But she did not mean that he wasn’t aware of the Holocaust or the Final Solution. She knew that once the Führer decided on physical liquidation, Eichmann embraced that decision. What she meant was that he acted thoughtlessly and dutifully, not as a robotic bureaucrat, but as part of a movement, as someone convinced that he was sacrificing an easy morality for a higher good.Margaretha von Trotta’s film is not a documentary, but it incorporates archival footage of the trial. The director felt the footage was essential because it let the viewer encounter Eichmann directly.Nearly every major literary and philosophical figure in New York chose sides in what the writer Irving Howe called a “civil war” among New York intellectuals — a war, he later predicted, that might “die down, simmer,” but will perennially “erupt again.”

This time, a new critical consensus is emerging, one that at first glimpse might seem to resolve the debates of a half century ago. This new consensus holds that Arendt was right in her general claim that many evildoers are normal people but was wrong about Eichmann in particular.

Hannah Arendt in her Manhattan apartment, 1972. Hannah Arendt (1906–1975) was one of the most influential political philosophers of the twentieth century. Born into a German-Jewish family, she was forced to leave Germany in 1933 and lived in Paris for the next eight years, working for a number of Jewish refugee organisations. In 1941 she immigrated to the United States and soon became part of a lively intellectual circle in New York. She held a number of academic positions at various American universities until her death in 1975. She is best known for two works that had a major impact both within and outside the academic community. The first, The Origins of Totalitarianism, published in 1951, was a study of the Nazi and Stalinist regimes that generated a wide-ranging debate on the nature and historical antecedents of the totalitarian phenomenon. The second, The Human Condition, published in 1958, was an original philosophical study that investigated the fundamental categories of the vita activa (labor, work, action). In addition to these two important works, Arendt published a number of influential essays on topics such as the nature of revolution, freedom, authority, tradition and the modern age. At the time of her death in 1975, she had completed the first two volumes of her last major philosophical work, The Life of the Mind, which examined the three fundamental faculties of the vita contemplativa (thinking, willing, judging).

Arendt published the most controversial work of her career in 1963 with Eichmann in Jerusalem. Arendt covered Eichmann’s trial in Isreal as a correspondent for The New Yorker in 1960, when Isreali security forces had captured the S.S. lieutenant colonel responsible for the transportation of Jews to death camps. Eichmann in Jerusalem is the collection of revised articles from her coverage of the trial. According to her text, Eichmann had not had a sadistic will to do evil, but had been thoughtless; he had failed to think about what he was doing. Her concept of the banality of evil caused considerable friction between herself and the organized Jewish community, as her book was read by some as an elevation of Eichmann’s character and a questioning of Jewish innocence. Arendt was concerned that the ability to act according to conscience and rational thought was becoming obscured by partisanship and nationalism, combined with modernization. Most of her writing studies the sense of a shared world and the possibilities of freedom grounded therein.

Winner of Lola Award (German Oscar) for Best Actress for Barbara Sukowa and Silver Lola (2nd prize) for Best Film