The film takes place in present-day Iran, a modern nation trying to live under strict Islamic law. The film’s story has no quarrel with the Islam system, but demonstrates how an inflexible application of the letter of the law frustrates the spirit of the law. This is also a movie with an up-close and personal view of day-to-day social intricacies of life in Iran unlike any seen before. Its world is that of the sophisticated, well-educated middle-class residents of Tehran, people who have problems and personal situations much like our own. And it arrived at a time when other Iranian filmmakers (like the more overtly political Jafar Panahi) are being forbidden to work there.

Nader and Simin (Peyman Moadi and Leila Hatami), a happily married middle-class couple in Tehran, have a sweet 11-year-old daughter, Termeh (Sarina Farhadi); Nader’s senile father also lives with them. Simin (Leila Hatami) wants to leave the country with her daughter, Termeh (Sarina Farhadi), and Simin’s husband, Nader (Peyman Moadi), insists on staying at home in Tehran to care for his frail and elderly father, who suffers from dementia and needs constant attention. “But he doesn’t know you!” his wife says. “No, but I know him.” Both are correct. Here we have the universal dilemma of Alzheimer’s care.

The partial split between Nader and Simin is only one of the schisms revealed in the course of a story that quietly and shrewdly combines elements of family melodrama and legal thriller. Because Nader refuses to agree to a divorce or to give the legally required permission for his daughter to travel abroad, he and Simin find themselves at an impasse. Simin moves to her mother’s apartment, and as a necessity sues for divorce, although the two want to remain married.

The case shows up in the office of an interrogating judge (Babak Karimi), whose task is to hear evidence and evaluate it. The conflict between the two families, which often turns on forensic details and uncertain recollections, is inflamed by social tension. The interrogating judge is a fair man, open-minded, and all the witnesses testify as truthfully as they can. But none of them have possession of all the facts, and the findings must be in accordance with religious law. Nader and Simin are moderate Muslims. Razieh is so religious that she questions whether she can change the underpants of a man, even though he is so old and sick. What drives her is the family’s desperate poverty.

The writer-director, Asghar Farhadi, tells his story with a fair and even hand. Although the

Director Asghar Farhadi, whose four previous films include another Berlin prize winner, 2009′s “About Elly,” has chosen his title with care. This incisive look at Iranian society reveals, without calling any special attention to it, divisions over class, over religious observance, over political philosophy. But what’s so inspired here is his decision to ground them all in the most personal of all separations, that between a husband and wife.

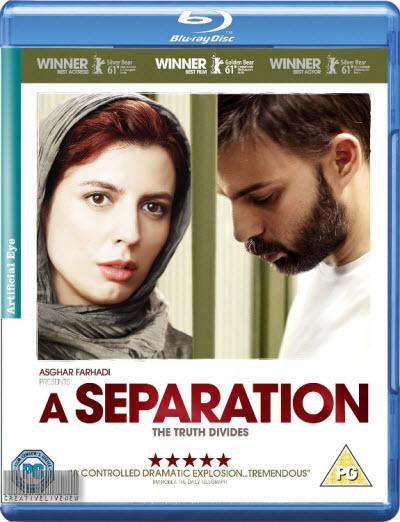

A SEPARATION: Written, produced and directed by Asghar Farhadi; director of photography, Mahmood Kalari; edited by Hayedeh Safiyari; sets and costumes by Keyvan Moghadam; released by Sony Pictures Classics. In Persian, with English subtitles. Running time: 2 hours 3 minutes.

WITH: Leila Hatami (Simin), Peyman Moadi (Nader), Shahab Hosseini (Hodjat), Sareh Bayat (Razieh), Sarina Farhadi (Termeh), Babak Karimi (Judge), Ali-Asghar Shahbazi (Nader’s Father), Shirin Yazdanbakhsh (Simin’s Mother), Kimia Hosseini (Somayeh) and Merila Zarei (Ms. Ghahraei).