Modern tabloids have some terrible headlines, but it would be wrong to assume that the print media of the nineteenth century were necessarily more sensitive. One newspaper reported the fire which killed George Lee and another under the title 'FIRE AND LOSS OF LIFE, EXCITING SCENE IN CLERKENWELL'.

However, the events of that July evening in 1876 were certainly dramatic. John Smith, a hatter in St John Street, was in his shop at eight in the evening when he noticed that smoke was coming from the back room. Before he had chance to warn the lodgers upstairs, the fire had cut off access to them and they were trapped.

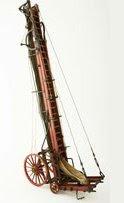

A wheeled fire-escape machine was brought to the premises. Such fire ladders were originally provided by the Society for the Protection of Life from Fire, but were now under the responsibility of the Metropolitan Fire Brigade. They could reach up to 60 feet high and had a canvas chute so that people being rescued did not have to descend the ladder rungs. Each ladder was kept locally in a watchbox, accompanied by a fireman who kept watch at night and was responsible for operating the machine if it was needed. The firemen's life was not easy: they lived at the fire station and worked for low wages. Most were ex-seamen as Eyre Massey Shaw, head of the Brigade, valued their training and discipline. One of his advertisements for firemen read:

A wheeled fire-escape machine was brought to the premises. Such fire ladders were originally provided by the Society for the Protection of Life from Fire, but were now under the responsibility of the Metropolitan Fire Brigade. They could reach up to 60 feet high and had a canvas chute so that people being rescued did not have to descend the ladder rungs. Each ladder was kept locally in a watchbox, accompanied by a fireman who kept watch at night and was responsible for operating the machine if it was needed. The firemen's life was not easy: they lived at the fire station and worked for low wages. Most were ex-seamen as Eyre Massey Shaw, head of the Brigade, valued their training and discipline. One of his advertisements for firemen read:Candidates for appointment must be seamen; they should be under the age of 25, must measure not less that 37 inches round the chest, and are generally preferred at least 5 feet 5 inches in height. They must be men of general intelligence, and able to read and write; and they have to produce certificates of birth and testimonials as to character, service etc. Each man has to prove his strength by raising a fire escape single handed with the tackle reversed.

After they have been measured, had their strength tested and been approved by the chief officer as stout, strong, healthy looking, intelligent and in all other respects apparently eligible, they are sent for medical examination before the surgeon, who, according to his judgement, either rejects or passes them, in either case giving a certificate.Two such firemen - one the man responsible for the machine - climbed the fire-escape to the second floor of the St John Street shop and brought one man down. They then rescued a badly-burned woman, but the flames were now threatening the escape itself. A third woman was brought out of the building to the escape, but it was now on fire and its 'chocks' gave way. As a result, it broke into two and the woman, the two fireman and another volunteer fell to the ground. One of the firemen, George Lee, was holding the woman in his arms.

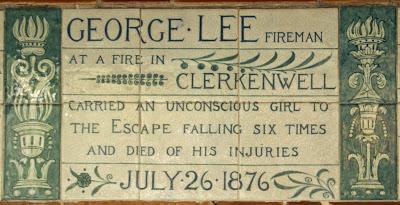

The woman who fell with the escape and her children, aged 17 and 15, were taken to hospital. The charred remains of another woman were found later in the building. The two firemen were also in need of hospital treatment; George Lee would die of his injuries about two weeks later. He had suffered severe burns which were the cause of 'lockjaw'. Lee was buried at Abney Park Cemetery, at a funeral attended by police, firemen and thousands of members of the public. At his inquest Massey Shaw, chief of the Fire Brigade, described his conduct as 'the greatest act of bravery ever shown by a fireman'. His courage is recorded (not entirely accurately) on the Watts Memorial:

GEORGE LEE, FIREMAN, AT A FIRE IN CLERKENWELL CARRIED AN UNCONSCIOUS GIRL TO THE ESCAPE FALLING SIX TIMES AND DIED OF HIS INJURIES JULY 26 1876.