Velcro® was inspired by the grappling hooks of burrs. Supersonic jets have structures that work like the nostrils of peregrine falcons in a speed dive. Full-body swimsuits, now banned from the Olympics, lend athletes a smooth, streamlined shape like fish.

Nature’s designs are also giving researchers funded by the National Institutes of Health ideas for new technologies that could help wounds heal, make injections less painful and provide new materials for a variety of purposes.

Quill Skills

The quills of the North American porcupinefeature needlelike tips armed with layers of 700 to 800 microscopic barbs. As curious dogs and would-be predators discover, the backward-facing barbs make it agonizing to remove the spines from flesh.

To scientists, the flesh-grabbing ability of quills point to myriad applications. Take, for instance, the work of Jeffrey Karp of Harvard University, Brigham and Women’s Hospitaland the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and his Harvard/MIT colleague Robert Langer. These researchers created disks of medical tape impregnated with microscopic barbs. They are testing the patches as tools to repair hernias or close surgical wounds and thinkthe disks might have advantages over the meshes and staples currently used. Porcupine quills have given researchers new ideas of how to make medical devices and materials with desired characteristics.

The same researchers recently examined porcupine quills from a completely different perspective. What intrigued them most was not how difficult the quills are to remove, but how readily the shafts penetrate skin. Barbed quills slip into flesh even more easily than ones with no barbs — or than hypodermic needles of the same diameter.

The scientists discovered, to their surprise, that a quill’s puncture power comes from its barbed tip. Barbs seem to work like the points on a serrated knife, concentrating pressure onto small areas to aid penetration. Because they require significantly less force to puncture skin, barbed shafts don’t hurt as much when they enter flesh as their smooth-tipped counterparts do.

To the researchers, barbed quills are a starting point for designing needles that deliver less painful injections. To get around the prickly—and potentially painful — problem of withdrawing barb-tipped needles, the scientists suggest creating synthetic barbs that soften or degrade after penetration, or placing barbs only on areas of the needle where they would aid entry but not hinder exit.

Gecko Grip

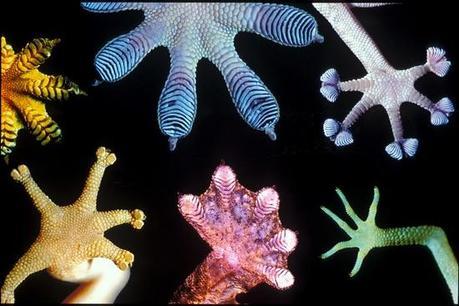

Geckos can skitter up walls and walk along ceilings because their feet are covered with a dense mat of fingerlike projections. Each projection, a few thousandths of an inch long and many times thinner than a human hair, ends in a tuft of hundreds of nanoscale fibers called spatulae. The tip of each spatula broadens and flattens into a rounded triangle, rather like a kitchen spatula. Together, the nanoscale spatulae vastly increase the contact area between a gecko’s foot and a surface.

With lizard feet in mind, Karp and Langer created a biocompatible medical adhesive that features a pattern of nanoscale pillars to maximize contact area. The material can stick to a variety of tissue surfaces, including those that are irregular and change shape.

Unfortunately, the material isn’t sticky enough to create an airtight, waterproof seal, so it can’t be used by itself on internal organs. In contrast, existing medical-grade glue can seal wounds tightly and quickly, but it can also cause tissue irritation.

The scientists combined the two products to create an ideal solution: a gecko-inspired tape coated with a thin layer of glue. The new tape conforms closely to surfaces, the glue seals any small gaps, and the entire product is nonirritating to tissues. These features could make it suitable for applications like repairing blood vessels or sealing up holes in the digestive tract.

Every part of a spider web is strong and elastic, but only some strands are sticky. These features inspired scientists to design a medical adhesive that is more gentle on delicate skin.

Silky Stickiness

Spider silk is strong (five times stronger than steel by weight), stretchy and lightweight. Some silk is sticky to catch prey, and some is not to let the spider scurry along it.

Karp, Langer and their postdoctoral associate Bryan Laulicht sought to create another new medical product with similar properties—a pliable, peel-off adhesive that doesn’t damage the underlying surface when removed. This sort of tape would be especially valuable for keepingtubes or sensors in placeon those with delicate skin, including newborn infants and elderly people.

For reference, the scientists initially turned to traditional medical tape, which, like household masking tape, is made by spreading a sticky adhesive onto a thin backing material. But instead of spraying the backing with adhesive right away, the researchers first applied a silicon-based film. Then, with another nod to the nanoscale pattern on gecko feet, they used a laser to etch a microscopic grid pattern onto the film. Finally, they added the sticky layer.

Along the grid lines, where the laser burned away the film, the backing touches the adhesive and the product acts just like normal sticky tape. In areas untouched by the laser, the backing floats on the silicon film and lifts off easily, leaving behind a layer of adhesive that either wears off naturally or can be rolled off with light finger pressure.

In essence, the resulting product has some sticky and nonsticky areas, just like a spider web. It goes on easily, adheres well and, best of all, comes off gently, even when pulled rapidly in an emergency situation.

Karp isn’t surprised that studying the natural world can reveal solutions to medical challenges. “I strongly believe that evolution is truly the best problem solver,” he said, adding that we still have much to learn from nature.

Learn more:

Video About Jeffrey Karp’s Research

Also in this series:

Nature: The Master Medicine-Maker

his Inside Life Science article was provided to LiveScience in cooperation with the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, part of the National Institutes of Health.