I had a double mastectomy a week ago, which for the context of this article means two things: 1) I was unable to participate in the March For Our Lives yesterday, although I really wanted to; and 2) I’m not in a particularly charitable mood. You might even say, in fact, that I’m feeling extra protective of this fragile corporeal vessel I’m forced to inhabit.

Right before the mastectomy, during the National School Walkout on March 14, most of us were seeing nonsense on social media about “walk up, not out,”[1] meaning: instead of walking out of school to protest the fact that it’s not a safe place for kids and teens, why don’t you walk up to classmates you think might be the next Nikolas Cruz and talk to them in order to…this is where things get fuzzy. But presumably in order to keep them from becoming the next Nikolas Cruz.

I am no longer a child and I do not have children, but what I do have is two teenage siblings, and I will be absolutely, thoroughly god-damned before I instruct them, or allow anyone else to instruct them, to do something so equal-parts patronizing and dangerous.

Since I don’t have much to do these days besides read and monitor my surgical wounds, let me break this down.

Adults are historically terrible at dealing with social exclusion in schools

I’m not surprised that at the heart of this infuriatingly condescending meme lies a fundamental misunderstanding of social dynamics among children and teens, because adults (at least, the ones who don’t study this academically) seem to have always had difficulty grasping what most kids (yes, even the “socially awkward” ones) know intuitively.

When I was little, this manifested itself in ways such as classroom rules (formal or informal) about having to give a Valentine’s Day card to each student in the class, or invite each student in the class to your birthday party, so that nobody feels excluded. Never mind what a creepy message this ultimately sends, or how humiliating and uncomfortable it would be (and was, for me at times) to receive cards and party invitations from kids that you know hate you.

I don’t know if kids still give out Valentines, but I do still see headlines now and then about elementary and middle school students being forced to say “yes” to anyone who asks them to a school dance [2], or being banned from having “best friends” so that nobody feels excluded [3]. To these things I can only say: yikes, you guys. Yikes. Are the adults okay? Who hurt you? (Apparently, the kid in your 6th grade class who said no when you asked them to the dance.)

What kids know, and what many adults apparently quickly forget, is twofold: 1) Social exclusion will be a part of our lives in some way no matter what; and 2) if people want to exclude you, there is nothing—no rule, no requirement, no sugar coating—that will hide that fact from you, or make it sting any less. In fact, one of the most hurtful and memorable forms of bullying a child can experience is having their classmates pretend to like them, care about them, or include them (to the praise of parents and teachers, probably) only to yank that positive regard away. This isn’t a new thing. Hasn’t anyone seen Carrie?

Social exclusion isn’t a childhood phenomenon; it’s a human phenomenon that many adults also experience in their social groups, workplaces, and communities. There’s no simple answer to it, and any effective intervention would probably have to address the prejudices that people use to decide whom to exclude, rather than the exclusionary behavior itself. But that’s for another article, or rather, for another book.

All social exclusion is not made equal

Another mistake adults make when trying to mitigate social exclusion in schools is assuming that it’s all cut from the same cloth. Sure, on the surface, the behaviors can look the same—ignoring or avoiding certain students, laughing at them, refusing to sit with them at lunch. But the motivations behind these behaviors can vary a lot.

That means that on the surface, you can’t really tell if a group of kids is avoiding another kid because they think his hand-me-down clothes are ugly, or because he’s a pompous asshole who makes them feel small and dumb whenever they try to talk to him, or because something about him is just…off in a way they can’t articulate but that reminds them of when their parents told them to avoid that creepy old dude down the block because “we’ve heard stories.”

Kids, especially younger ones, don’t always know how to make sense of their feelings in that last case. So they sometimes act out those feelings by passing mean notes about that classmate or making fun of his dark baggy clothes or the music he listens to. It’s mean. But it’s covering up for something else that they haven’t been taught to name yet.

(I do wonder, though, how true that even is in today’s landscape. I do know that ten years ago when I was a high school student, I could never have even contemplated mounting the sort of campaign the Parkland students have, as have the many young people of color protesting gun violence during the past few years. I just didn’t have the schemas to understand it. Today’s teens are different.)

In any case, in situations where a school shooter was bullied or excluded prior to his acts of violence, it’s possible that the social ostracism was less a cause and more a warning sign. Maybe his classmates knew something was up, but they didn’t know what, and they didn’t know how serious it might turn out to be.

This means that when you encourage students to “walk up, not out,” you’re not just asking them to walk up to the new kid, or the disabled student, the girl who’s been made fun of ever since she got her period in gym class, or the gender-nonconforming young person. You’re also asking them to walk up to the young white man with violent lyrics plastered all over his locker, who nobody ever wants to talk to because all he wants to talk about are his guns and the need to keep the white race pure or whatever.

Imagine, too, being the new kid or the disabled student who suddenly has a bunch of kids “walk up” to you right after the National School Walkout, only to realize that they’re doing it because they’re afraid you’ll shoot them.

Bullying does not cause school shootings

The idea that the prototypical school shooter is necessarily a “troubled” young person who is cruelly bullied and excluded by their peers is not necessarily based on reality. Even in the case of Columbine, the typical example, it’s straight-up false. [4]

It is often very difficult to put all the puzzle pieces together after the fact and figure out whether a shooter was mistreated by their peers or not, especially if that shooter has committed suicide and isn’t around to answer questions.

Part of what makes it difficult is that social dynamics among kids and teens are extremely fluid and can change by the day. Very few kids are always the victims, always the bullies, or always the bystanders. If you examine random slices of my K-12 life, you will find times when I was mistreated and left out, times when I had a healthy, supportive group of friends, times when I stood by while my friends bullied others, and probably even times when I was the bully. If you read my teenage diaries, you might find some wildly conflicting evidence in there.

Here are some characteristics that many (possibly even most?) school shooters have in common, that aren’t being bullied or excluded: being white, being male, having a record of violence or harassment against women, having an interest or a record of participation in white supremacist/neo-Nazi/ethno-centrist groups. (Another item that doesn’t belong on this list? Mental illness.)

Really, if you wanted to prevent school shootings without having kids walk out of schools and march to demand action on gun control, it almost seems like the most effective strategy wouldn’t be making sure all the loners feel included, but that we intervene when we see young people developing strong sexist and racist beliefs. Almost.

There’s some value in encouraging kids to include each other

That’s not to say that the underlying message of “walk up, not out” is entirely bad. From a totally basic, uncomplicated point of view, sure, it’s nice to encourage children and teens to consider who might feel left out at their school and try including those people. I would endorse that statement in about the same way that I would endorse statements like “it’s good to eat vegetables” and “we should try to drive within the speed limit whenever possible.” That is, I agree, but I’m not about to put it on a bumper sticker or tattoo it on my body.

The generally uncontradictory nature of that statement is probably why many kids already do that. Most kids who are rejected and excluded by some classmates are accepted and included by other classmates. Most “unpopular” kids do have friends—friends who are often also unpopular and can relate to their experience. When I was getting bullied the most—seventh grade—I had a small group of loyal friends who liked me and hung out with me. They just weren’t necessarily in the same gym class.

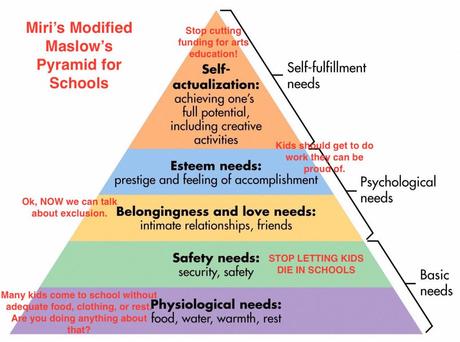

Being concerned with including other students and walking out to protest gun violence are not contradictory. In fact, they go together. Our schools should be places where all students feel that they belong—if not in every single social group or with their entire class, then in a club or group of friends where they feel wanted and welcome. However, before our schools can be those places, they need to become places where children do not fear being murdered with a gun. Remember Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. [5] Which of these do you really think we should start with?

Kids and teens can be as biased and prejudiced as their parents, but they also often have very well-developed gut instincts when it comes to unsafe people—unless we shame them into suppressing those instincts. We should challenge the young people in our lives to approach uncomfortable conversations with other young people who are different from them, while drawing a very clear line between that and disregarding one’s own personal safety. We should read The Gift of Fear by Gavin de Becker [6], discuss it with young people, and then stop demanding that they ignore all the good advice in it.

We should ask ourselves, too, which images pop into our minds when we think about asking kids to “walk up” to someone they’ve excluded. Do we imagine the Mexican immigrant kids, the Black kids, the gender-nonconforming kids, the girls who got labeled “fat” or “slutty,” the boys who wear nail polish, the kids who need IEPs? Or do we imagine the white boys who give Nazi salutes and submit essays about why slavery is morally justifiable?

What labor are we asking young people to perform, here? Which problems are we asking them to solve that we ought to be solving for them? Whose voices are missing from this conversation?

And why are we having this conversation, exactly? Is it because we’re so very worried about social exclusion, or is it because this is easier to talk about than guns?

[1] https://www.cnn.com/2018/03/14/us/ryan-petty-walk-up-walk-out-stoneman-douglas-shooting-trnd/index.html

(Sidenote: I feel quite bad about trashing an idea that seems to have originated from the father of one of the Parkland victims, but unfortunately, losing someone to this type of violence doesn’t necessarily give you the psychological, sociological, or legal expertise to determine how to prevent it.)

[2] https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/education/wp/2018/02/13/a-school-made-children-say-yes-to-any-classmate-who-asked-for-a-dance-then-a-parent-spoke-up/?utm_term=.06576c7f05b5

[3] http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/columnists/kass/ct-met-best-friends-ban-kass-0119-story.html

[4] https://www.facebook.com/rebeccawald/posts/10156114680017429

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maslow%27s_hierarchy_of_needs

[6] https://www.amazon.com/Gift-Fear-Survival-Signals-Violence/dp/0440226198

Brute Reason does not host comments–here’s why.

If you liked this post, please consider supporting me on Patreon!