In his 19 February review of Tim Miller's Deadpool, Entertainment Weekly critic, Chris Nashawaty likens Hollywood's current love affair with comic-book franchises to a "superhero-industrial complex" that has become "so monolithic and profitable" and flatly predictable that even die-hard fans of caped crusaders and marvelous mutants now shudder when expanded cross-overs, bloated sequels, and generic spin-offs are announced at Comic Con, the newly anointed Official Corporate Sphincter of mainstream Pop-aganda.

Eight years earlier, in the prescient and personal "Why I Hate Superheroes," Nashawaty himself warned of the coming deluge of masked miscreants in his fond homage to pre-blockbuster "Nerdvana," an earlier, innocent age when "no one had heard of Comic-Con yet and there were movies for everyone" during the season of big, brash air-conditioned escapism. That cogent, cautionary tale warned of the cultural fallout from the phenomenal success of Sam Raimi's Spider-Man and its "endless 121 minutes" of "F/X eye candy" which "couldn't have looked more bogus." Nashawaty well knew, as did many others, that the prepackaged, high concept gloss of comic-book properties would soon admit ravenous Hollywood wolves into the fairly cultish, sheltered shires that were home to quaint communities of comics, cards, cosplay, and role playing fans: "It felt like every studio head in town, itching to wet his or her beak with Spider-Man 's box office backwash, was trotting out any half-baked comic-book flick that had been pitched across their desks: even the ones with C-list avengers like Daredevil, The Punisher, and Ghost Rider. No superhero was too minor or crappy to be pulled out of the mothballs, tarted up, slapped on the ass, and turned into a bloated summer movie." In the annals of American culture, few harbingers have been as accurate in their dire predictions.

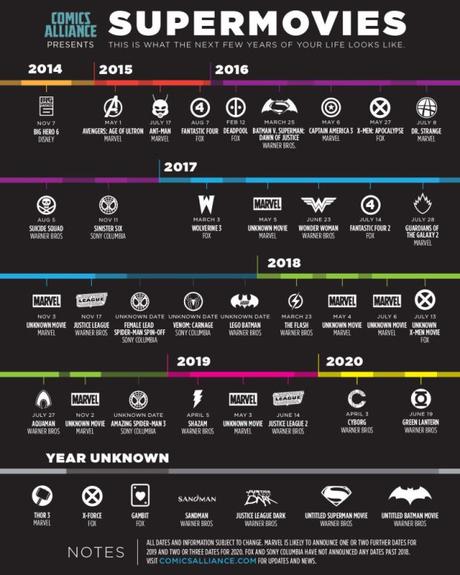

Now, in 2016, what the New York Times conceives as an "incessantly expanding comic book movie universe" shows absolutely no signs of slowing down its quantum mechanics. Some trends are truly exciting, especially in terms of comedy and humor. James Gunn's goofy space oddity, Guardians of the Galaxy , ABC's Agent Carter and Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. , and even the CW's Arrow and The Flash, Fox's Gotham, and CBS' Supergirl all offer a variety of fairly rewarding courses in caped comedy. Even dour concepts like Daredevil and the Punisher have been resuscitated and paired into one of the most anticipated Netflix series yet. Both Ant-Man and Aqua-man, hilariously satirized as fairly ridiculous properties by Nasthawaty in 2008, are well on their way to crowd-pleasing marquee magnetism, and we are bracing for the arrival of hordes of new super-flicks and costume-centered franchises well beyond 2018.

In recent years, much of this supersuit-saturated material has been wrestled and remediated from the fairly underappreciated and intensely personal "mid-1970s cultural moment" that made actual comic-book epics of all genres one of the most personal and inventive storytelling forms in American culture. Yet, their new big screen, CGI-clogged brethren are still closely keyed to the original modes and mythologies that kept fans swarming over newsstands, then convenience stores, and finally, "geek shops," or specialized hobby stores for more than three decades.

As Jeff Jensen explains, this "direct market" strategy helped to nurture and sustain small but devoted communities of readers who savored the cheap thrills, campy extremes, and surprising gravitas of epic super-hero mythologies: "By reducing the visibility of their product, they made it harder for publishers to attract new readers. Their solution? Keep current readers loyal longer by producing comics that were more mature, more sophisticated, more 'adult'" (Jensen 52). The fans and readers themselves were inherently cagey, frequently irksome, and eager to judge, deny, or assault anything which questioned or assailed what Henry Jenkins has described as their adamantly "participatory" subcultures. As Charlie Anders noted in 2007, "Comic book fans are known for their fanatical love for their favorite characters - and their ferocious scorn for anyone who dares to mess them up." It is this furious, and perhaps somewhat unique and beautiful fusion of love and scorn that I find most valuable to our understanding of what Tim Miller's 2016 super-movie, Deadpool, brings to this enormously convoluted landfill of super-noise and media mayhem.

In those early days of pre-Imax Nerdvana, when comics, super-heroes, and their consumers were mostly associated with juvenile illiteracy, stunted growth, questionable hygiene, and even (in the case of the great 1950s witch hunts chronicled by David Hajdu, Carol Tilley, and others) juvenile delinquency, both the comics and their fans kept one consistent defense against the scorn and disapproval of parents, teachers, "cool" kids, and other forces of conventional mainstream disappointment: Humor.

Robert Warshow recognized and appreciated the "oppositional" irreverence planted in his own son's dogged commitment to fervently satiric and blatantly subversive EC Comics like Mad Magazine and Tales from the Crypt as early as 1954 in his seminal " The Study of Man: Paul, the Horror Comics, and Dr. Wertham." Even the widely lambasted and discredited social scientist-come-muckraker, Frederic Wertham himself, eventually found the wild participatory humor of fanzines, newsletters, and proto-zines constructed by studious and exacting fans and critical readers to represent one of the most encouraging signs of individualistic engagement and empowering resistance to corporate systems of entertainment and influence.

But now, as Deadpool quickly confirms, the humor of irreverent opposition, and violently vituperative wisecracking has morphed and metastasized into something quite new and discomfitting for both traditional comics fans and movie-goers alike. Both "jokes and bullets are tossed like confetti" in what the New York Times calls Ryan Reynold's "breezily amoral" performance of an oddly pan-sexual, self-deprecating, and thoroughly lethal "roguish outlier." Throughout Deadpool, the sardonic comedy now seems well absorbed within, rather than proudly apart from or antagonistic toward, the all-consuming corporoborg of smothering super-kitsch. The New Yorker 's Richard Brody interprets both Reynold's amphetamine-driven portrayal of Marvel's merry "merc with a mouth" and the film's predominantly profane perspective on super-guys as "a signifier of the paradoxes of male adolescence." As Brody suggests, Deadpool "combines a nearly irrepressible aggression and defiance of authority with a self-aggrandizing sense of virtue, a seemingly strict and principled adherence to an authoritative sense of justice of his own making. He's a self-fashioned bad boy who's in no way evil.He's also a swaggering, hard-drinking hedonist-bro who's nonetheless looking for love, and, in the sewer pit of a bar that he frequents." All of this is undoubtedly accurate, and there are plenty of macho boys and boyish men who truly embrace, admire, and celebrate the character's chimichanga-chomping, devil may care knack for violent and contrary mischief.

Yet, there is another bolder, harsher theme beneath Reynolds' Deadpool and Miller's comedy. As a past master of military murder, a desperate lover willing to sign on for anything to save his relationship for the malignancy that eats out his insides, an expertly recruited and fiendishly abused "grunt" left mutilated and scarred by a strange crew of international super-slavers, and a deeply bruised and broken hero achingly afraid of rejection and ridicule by those he loves, Deadpool is also a freakish 21st century Frankenstein: a creature embattled, burned out, and belittled by the slick promises, special interests, and sadistic tendencies of other, more menacing and malevolent militias. If the Deadpool persona speaks to adolescent male fantasies of rebellion and recklessnesss, it is also a poignant Pagliacci or Pierrot of PTSD, post-military haplessness, and the desperate driving need for swift and vicious closure relating to an entire generation of veterans, "contractors," and professional soldiers left wounded, anxious, and wondering about the forces that made them what they are. Reynold's heartfelt barside confabs with T.J. Miller, and perhaps most of the one on one conversations Deadpool enters whenever his defensive bravura takes a moment's rest, all drip with intimate, yearning catharsis and psychic triage. Just as Superman, Spider-Man, and Wolverine spoke to legions of outcasts, misfits, and weaklings in their time, Deadpool now nurtures and ministers to the shattered masses of those who have lost parents, siblings, friends, and neighbors to the wide-ranging shrapnel of Iraq and Afghanistan.

Both fan and critical discourse surrounding Deadpool makes much of its self-deprecating opening bloothbath of a title sequence, as well as the quirky character's semi-schizophrenic tendency of snarking directly to the audience. As the New York Times observes, "Breaking the fourth wall is old stuff, especially in comedy and, like pokes in the ribs and stage winks, can be a way filmmakers signal the audience that we're all in this together." Unlike the wry asides of Groucho Marx, the smart-alec comebacks of the guys and gals of Screwball comedy, the self-reflexive parodies of Mad, Panic, and Cracked, or even the slick nodes of rebooted identity embedded within Edgar Wright's Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World, on which Deadpool's director honed his craft, the poignant pleasure in such moments arises from their spontaneity which fuels, in comedians' terms, the killing orwithering accuracy of the asides. There are plenty of these in Deadpool. As nearly every review admits, the script, the character, the direction, and Reynolds himself are periodically, unquestionably funny. Fan and critic each adore Deadpool's harping on the somewhat chintzy use of second banana X-folks to bolster this "naughty" mess of "Hard-R fun." As even Nashawaty admits, "it's a superhero film for the wiseasses shooting spitballs in the back of the school bus." Still, it remains just a bit discouraging that the class clown's private rebellion, the nerd's geeky chic, and the struggling soldier shoved "back in the word" have all been folded into the Super-glue of mainstream media megaflicks?

There is also something else in Deadpool. In fact, there are quite a few other things that many critics seem to miss or ignore. I should now clarify that I am not a Deadpool fan or apologist, nor a great lover of super-media, or even especially interested in self-conscious asides outside of Shakespeare and Moliere. In fact, I was hesitant to even see Deadpool on opening night, except for the offer from a good friend to share costs and buy drinks. Still, as the prodigal son of superhero movies, Deadpool does do one thing beautifully well in terms of humor. It is one of very few super-flicks to actually emphasize witty taunting, snide mockery, and deliciously sarcastic cajoling over pure brute force and post-9/11 spectacles of allegorical destruction almost always centered around New York City or its many comic-book doubles. Studly star, Ryan Reynolds is physically impeccable until his gruesome mutation, but, as the movie emphasizes, his indomitable "sense of humor" is always his most reliable and compelling weapon. With the exception of a few brisk moments featuring the sidewise comments of Robert Downy Jr from John Favreau's Iron Man and Joss Whedon's Avengers , the requisite comebacks, jeers, and villain- maddening ripostes are woefully missing from nearly all super-movies and their rather tedious entourage of orbital merchandise.

This same lack of smart-alec jeers and insults permanently crippled Sam Raimi's genre-defining Spider-Man films. For an auteur so celebrated for witty, slapstick subversion of horror and action motifs, Spidey's dearth of deft retorts felt oddly uninspired. Even if the Green Goblin and Dock Ock were physically bested, Spider-man's victories seem ultimately tepid and anticlimactic to anyone who had thrilled to the zippy mockery which made sad sack science nerd Peter Parker's other life as a wiseacre rock star super-hero so liberating in the original comics. Much like Spider-Man, or Wolverine, or the Teen Titans, or Rocket Raccoon or even "The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl" for that matter, Deadpool, both the film and Reynolds' performance, are loaded with explosions of oddball, eclectic, and occasionally outré masturbatory speech. He blusters his way through intimidating the odd stalker. He sexes up his kooky, kinky pillow talk with Morena Baccarin's Vanessa (perhaps soon to become the equally badass riotgrrl Copycat/ Lady Deadpool?). He undermines the torturous mutantizing transformation in the film's least interesting and most clichéd scene, slaughters a vast network of criminals in a variety of gruesome ways with matching mockery, and nearly "wins the movie" with his lovingly crass commentary about whacking off with a tiny embryonic hand after using it to comfort his makeshift mommy, played with perfectly pitched "Who gives a f**k?" indifference by Leslie Uggams as "Blind Al."

In the somewhat disjointed finale, Reynold's best moments are not particularly brutal or violent or even F/X-driven. Instead, he seizes the day and the girl by berserkishly belittling legions of thugs, goons, and the totally forgettable bad Brit villain, Ajax, who has almost nothing to do in the entire show except glower and bleed. Again and again, Miller's film and Reynolds' performance privilege the dirty comedy of good, old-fashioned wit and innuendo, peppering their dialogue with quirky references to Voltron, Wham, "Dutch ovens," Jose Conseco, and Bernadette Peters. Instead of Matrix-level gun battles or Lord of the Rings spectacle, Deadpool perpetually forgets his duffle bag full of ballistic justice and centers his Alamo around a decrepit and decaying S.H.I.E.L.D. helicarrier that somebody in a more pretentious franchise film seems to have left lying around. Time and again, "Reynolds fires off so many rimshots in the first five minutes that he comes across like Don Rickles in spandex," and his bro-mantic banter with Hindi cabbie, Dopinder, offers more funny surprises than any other running gag in the yuck-a-thon. Even the film's filthy final punch line, which cements Deadpool's romantic victory over both super-villainy and uber-uglification, is saved for Baccarin, rather than Reynolds and she delivers it with bright eyed, unabashed gusto!

Which brings me to the last few triumphs of Tim Miller's cockeyed, potty mouthed, smut-ridden, proudly perverse and adamantly adolescent slaughterfest. These are, quite surprisingly, its women. All of them. From Gina Carano's "big mama" baddie, Angel Dust, to the scene-stealing ultra-sulk of Briana Hildebrand's X-intern, Negasonic Teenage Warhead, the women of Deadpool might be busty, lusty, butch and brash, but they are neither needlessly objectified nor victimized damsels in distress. They punch, blast, text, punish, pout and love their way into the melee and they rarely succumb to stereotypes beyond those they themselves find playful or empowering. This might be one of the film's most significant improvements or innovations within a genre of titanically over-sexed, hyper-violated super-babes.

Baccarin herself takes bold and plentiful risks with her Vanessa, a tattooed "Calendar Girl" of tough, tarty fun who remains thoroughly in control of her dynamic sexuality from start to finish. Her coital scenes with pre-yuckified Reynolds are definitely some of the funniest, raunchiest sequences ever attempted in a super-movie, so much so that legendary lothario, Tony Stark, might shudder in terror while Lady Gaga herself cries out, "She's a free bitch, baby!" If only Sam Taylor-Johnson's tedious 50 Shades of Gray had been made with half as much unfettered, erotic energy as Baccarin's several scalding hot, playfully pervy minutes in Deadpool. If there is a single part of Miller's blatantly bawdy bastardization of the super-story that we leave wanting more of, it is definitely Baccarin's vivid and vivacious Vanessa.

Ultimately, there is a lot of outrageous and perhaps unnecessary extremity in the blackly humorous, bleakly angry world of Deadpool. Its comedy is, as Manohla Dargis claims, "a somewhat compromised pleasure," but to ignore, belittle, or deny the truly rich, right, and shockingly blue moments of humor, heroism, and heady ingenuity that punctuate an otherwise perverse and disjointed super-property is to toss out the chimichanga without even tasting its somewhat questionable contents.

References

Anders, Charlie. "Supergirls Gone Wild." Mother Jones. July/August 2007:71-72. Print.

Brody, Richard. "The Deadpool Phenomenon and the American Male." The New Yorker. The New Yorker.com. 18 February, 2016. Web. 20 February, 2016.

Dargis, Manohla. Review: 'Deadpool,' a Sardonic Supervillain on a Kill Mission." New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com. 11 February, 2016. Web.

Jensen, Jeff. "The Amazing Adventures of a Comic Book Kid." Entertainment Weekly. 11 January, 2009: 49-52. Print.

Nashawaty, Chris. "Deadpool" movie review. Entertainment Weekly. 19/26 February, 2016: 98-99. Print. 98-99.

_______. "Why I Hate Superheroes." Entertainment Weekly. Summer TV Preview 3 June, 2008: 76-77. Print.

Schurstahl, Alan. "Deadpool motormouths filthily through Better-Than -Usual Superhero Stuff." LA Weekly. LAWeekly.com. 7 February, 2016. Web. 10 February, 2016.