Making decisions in times of rapid change

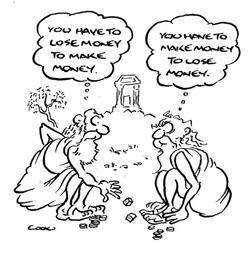

Depsite rigorous analysis, their decisions are still a guess. What’s more, it’s not a guess about whether they are right. It’s a guess about whether or not other people think that other people will think they are right.

After all, if for some reason you think the price of oil is going to go up and you think everyone also thinks that everyone else will think that, then there’s a good chance the price of shares in oil companies will go up.

But they might not. Investors might be more concerned about war in the Middle East. That’s how markets work. Nobody really knows.

It’s no different for entrepreneurs

John Maynard Keynes compared the phenomenon to a beauty contest in which participants choose not the most beautiful entrant but the one they think others would choose as the most beautiful.

Getting this right is getting harder. Change has become such a constant that we can now seem permanently perched at the edge of chaos. Just when things have settled down, another disruptive shift enters the marketplace.

There’s opportunity and danger here. The upside of approaching chaos is that it puts us on a steep learning curve. If we embrace it, we may push ahead of the competition. If we miss it, we’re left behind.

Say you are confronted by a change that demands a response. It might be your new idea or a new competitor. Can we de-risk our decision-making processes so that we not only navigate a reasonably safe passage but also take advantage of change, in order to thrive rather than simply survive?

Simple rules reduce risk

It is well proven that forecasts – of just about anything – are more often wrong than right. So when you isolate the direction in which you want to go, don’t just examine “what ifs”. Examine “what if nots”. Distrust opinions that are held too firmly. Limit your exposure to them. Have a budget and don’t put everything on black.

If elements of a new initiative fall into a high-risk category, can you outsource that element, or parts of it? It may curb the profitability of the outcome, but it will curb your losses if it fails.

Look for initiatives that align with what you are really good at. That’s not just the quality of your product or service. Maybe you have a superior way of creating ideas or distributing them to the market. Which of your options draws on your natural strengths?