With winter finally getting a grip on the land, Bob and I decided it was time for a hike along the Green River, near the small village of Whitevale, north of Pickering, Ontario. We try to make treks to this area during all seasons as it is fascinating to note the seasonal changes in the river and wildlife sightings. Our outing would be worth the effort.

Massive vines can be seen hanging from the cedar trees along the Seaton Trail, which runs alongside the river for over 12 kilometers. In some cases, the vines are substantial enough to bear an adult’s weight, and grow so as to create a swing.

On one past occasion, we came upon a Porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) with its head down low, moving along a deer track towards us. We, of course, watched its movements very carefully given that it looked cute and cuddly, but knowing that its sharp quills could be very dangerous.

The Porcupine was on a mission, apparently, as it quickly climbed up in a tree where it began to nibble the bark. Porcupines are Canada’s second largest rodent, with beavers being the biggest.

In the world that I grew up in at Oxtongue Lake, Ontario, both porcupines and beavers were, and still are, very common animals seen out in the bush. Porcupines are herbivores, with their favorite food being leaves and plants, however in the midst of winter, they switch to eating the bark off trees. This porcupine was doing a good job of stripping the limbs on this tree.

When Bob and I were in the Kalahari Desert in South Africa last year, we were lucky enough to find some quills from a couple of different Crested Porcupines, which are the world’s largest porcupines. These quills are upwards of 30 to 50 centimeters long (12 to 20 inches). The quills of our much smaller Canadian Porcupine are diminished in size when compared to those of the African species. Canadian porcupines have quills that are only 5 to 10 centimeters long (2 to 4 inches). Bob and I were thrilled to have found some quills of the African Crested Porcupines, but we were even more pleased that we didn’t bump into one in person (and I mean bump into one!!).

But we hadn’t gone to the Green River expecting to see a porcupine. We were hoping to see one of its bigger cousins, the Beaver (Castor canadensis). We know they are active along the river, having observed them in the past.

As we made our way along the trail, I almost missed seeing the busy Pine Grosbeaks grouped in a small bush. The females’ feathers camouflage them very well, and so it was the male that gave them away. The small black berries on the shrub were providing a valuable food source for the grosbeaks now that snow was covering most of the ground.

Continuing along at a snail’s pace, constantly searching the woods and trees for wildlife, resulted in us spotting a beaver. It was lumbering along the river’s edge with a mouthful of freshly cut tree limbs.

This little guy was obviously making his way to the river with his haul.

The beaver paused on a shelf of ice at river’s edge after dropping his twigs into the water. This fresh supply of food was destined for the beaver house further downstream.

Snow was beginning to fall as the beaver began swimming against the current in a northerly direction. The beaver did not even hesitate as it edged into the ice cold water being so well insulated with its waterproof fur.

There was a time in Canada, back in the 16th century, that the only business conducted was the Fur Trade. It was the single most important business that involved both Canada’s aboriginal peoples who had trapped as a way of life for thousands of years, and by European explorers and settlers who turned to fur trading as a way of life. Together, these two peoples paddled the rivers, set the traps, caught the animals, and then brought the furs back to the market. The number one animal they all strove to capture was the Beaver. Today, the beaver is the official emblem of Canada.

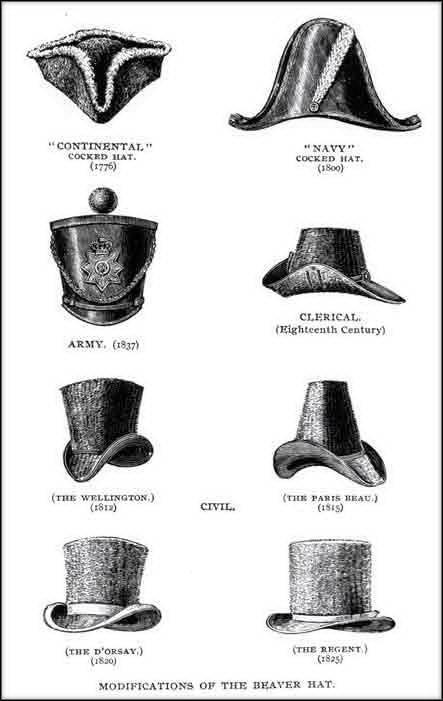

The reason they hunted beavers was because their fur could easily be turned into the Fashion Statement of the Day, which was Beaver Hats. This type of hat, in the 1700′s, was also popular because it was waterproof, enabling the owner to keep his or her head dry in a downpour. Fortunately, today, silk hats have replaced beaver hats as the most desired type of hat in the marketplace. And with mass conservation, and federal and provincial laws set down to protect beavers in Canada, the fat furry rodents are alive and doing very well all across our country.

Each summer, Bob and I head out on back country canoe trips along the very rivers and lakes that were once the roadways of Canada’s fur traders hundreds of years ago.

One of our back country canoe trips was plying the waterways of Frontenac Provincial Park, in Ontario, where we spied this beaver house. It is common to see beaver dams and beaver houses like this one on waterways all across the province. Frontenac Park is a world of rarely seen birds, wildlife, and beavers.

We didn’t stay in this location long enough to catch a glimpse of the beavers.

Instead, we followed the scat of a deer – its faint trail through the deep grass – before pinpointing its prone body beneath an evergreen tree. In the deep shade, the deer almost eluded us because of its stationary stance, only for the glimmer in its eyes. In no time, the deer bolted and raced across the meadow behind us.

And as we watched it racing away, Bob drew to my attention that a Praying Mantis (Mantodea) had landed on my back!!

Bob got a couple of pictures and then we convinced him to move along!!

Later, after we got our tent setup for the night, and with the loons calling out their song, a beaver decided to go for a late day swim right by our campsite.

Bob, like so many of his fellow Canadians, just loves to pick up a canoe and then carry it on his back in what we call portaging. Even I will carry it a short distance. It is really just a part of the way of life for many in my country. In fact, outback canoeing actually keeps both Bob and I connected to our families’ histories. Members of my family came to Canada in 1647, when the predominant mode of transportation was the canoe. Bob’s family, who came to Canada two hundred years later, also took to canoeing. And so over 300 years later, canoeing in the world of the beaver is just a given for both of our families, and it is something we share with many fellow Canadians.

Even today, my dad, Marvin, at age 89, still loves to canoe, and each winter, he spends time gluing, carving, and crafting paddles for both his use and ours the following season.

In this video that Bob filmed, my dad explains to us just how he glued and made the paddle that he holds in his hand. Everyone in our family has, at one time or another, been gifted with handcrafted paddles made by my dad. They have even been known to appear as wedding gifts for our daughter’s outdoorsy friends.

When Bob and I engage in back country canoe trips, he most often finds himself carrying the canoe for miles, along with other gear. I, on the other hand, am usually loaded down with everything imaginable!! In this picture, I am carefully making my way down a wet stony trail.

Part of canoeing can involve, if it’s safe, the art of running rapids. This is something that Bob and I take a lot of care in doing… no silliness and no running a rapids blindly. It is necessary to walk the river edge along the rapids, note the rocks, plan our canoe route through them, and then carefully take to the water.

Running rapids is a thrill, but it is the quiet backwaters that I most look forward to. I savour the peace and quiet knowing that it is a world of the unexpected.

As we canoed along a channel in Frontenac Provincial Park one time, I was excited to see in the distance this small muskrat sitting on a sunken log. We edged the canoe close enough to see that the muskrat was enjoying something to eat, and just when he felt no longer safe, the muskrat slipped beneath the surface of the water. What a cute little guy.

Pretty well every lake in Ontario has a family of loons that nest there. Here, we see a mother Loon carefully protecting her baby. It is the iconic lonesome call of a loon that every camper looks forward to. Something of the past always accompanies the eerie strains of a loon’s mournful cry.

This beaver swam alongside our canoe as we made our way upstream.

Seeing a beaver in the water doesn’t give you any idea just how big they can be. We caught this specimen as it made its way from one body of water to another…sort of portaging like we do. This one was along the Oxtongue River, near Oxtongue Lake in Ontario.

In this video, you get a chance to see the same beaver both in the water of Oxtongue River and on dry land.

As the colors of fall came to Ontario this year, Bob and I toured areas of Algonquin Park in order to appreciate the spectacular fall foliage. One stop we made was adjacent to this swamp where a beaver had made a massive dam.

With his video camera in hand, Bob documented both the beaver and some moose munching greenery along the swamp’s far shore. Seeing both the splendor of Algonquin Park’s colored leaves and two examples of wildlife on the same late fall day was simply amazing. I must mention, that this same day, we saw a wolf make strides across the highway, but in the video I shot, you can barely make out the gray form as it dipped into the marsh grasses along the road.

The beaver dam stretches across the full width of the area creating a gigantic pond for the beaver to live in.

We had waited for the better part of an hour, in anticipation of a moose stepping from the cover of the forest, but this beaver entertained us for the duration as he worked on the dam.

At long last, two of the three moose that had been frequenting this beaver pond emerged at the fringe of the trees.

In this video, you get a chance to see the beaver swimming near its dam as well as a male and female moose that were grazing at the edge of the swamp.

We have been fortunate to see so many beavers over the years. Hopefully, the beaver colony on the Green River in Pickering continues to thrive like those that are protected in the waters of Frontenac and Algonquin Parks.

As we observed this beaver, both he and his mate made routine trips into the brush in search of more green twigs and then back to the river. They both worked relentlessly until we had to give up our surveillance due to dwindling late afternoon light. It was particularly amusing to see them slip and slide down a short groove in the snow to speed their arrival to the water’s edge. They worked the same route over and over again, perpetuating the old saying “busy as a beaver”.

Frame To Frame.ca