The passage started benignly enough, once we got going. Although the weather watch to depart began the day we arrived in Bermuda, there were people to see and boat parts to fix, and a week felt sufficient. Plenty of time all around, really: there were three weeks before we needed to be in Connecticut and our passage time, in good conditions, should take only three or four days. What was there to worry about?

Plenty, it turns out. Systems come from multiple directions: you have to watch for cyclonic weather spinning up from the tropics, and lows rolling off the US east coast. We’re out of the trades and into the realm of variable winds (e.g., no consistent and reasonably predictable wind direction and strength), with convective weather—squalls—to keep things exciting. Day after day, reports showed either potential heavy weather conditions to avoid, or an unstable forecast marked by significant disagreement between weather data sources about what might happen. A clear weather window for the passage proved elusive, as we have no interest in tempting fate.

At one point it seemed like we wouldn’t even make it to Essex in time for our June 21 presentation (now that was an email I didn’t want to write the event organizers). So when the various models Jamie monitors for weather forecasts finally resolved into agreement – and with conditions looked reasonable- we dove into passage prep and were on our way in a couple of days.

We hauled anchor at dawn in the placid bay inside St George’s. The first day was a gentle beginning, sailing north over the top of the bank to the west of the islands. A small pod of beaked whales—Cuvier’s beaked whale, possibly (any cetacean jockeys able to ID from the fuzzy pictures below?)—were the sentimental boost to a perfect day of comfortable sailing. If only it had lasted! By evening, the wind and seas combined to make life on Totem more bouncy than is comfortable.

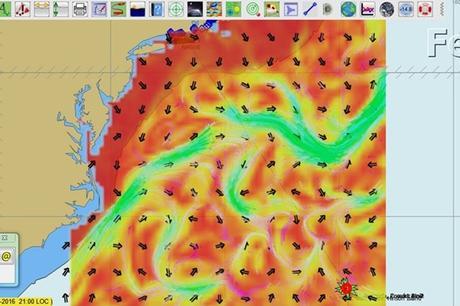

One of the significant dynamics in this passage is the Gulf Stream, a fast, warm ocean current that flows northwards along the US east coast, bending out and across the Atlantic towards Scotland and Norway. In our path, we’ll cross it at points where speeds may be up to 3 knots. When wind direction opposes current, the Gulf Stream is a famously miserable place to be.

We didn’t cross it until our third night at sea, and at a time that the wind and current aligned, making the passage relatively smooth. But beginning the first evening and lasting for the next couple of days, the swirls and eddies to the east of the main force of the stream created very uncomfortable sea state.

The dominant current stream bears close watching and careful planning to avoid when wind opposes current, but it’s the smaller flows spinning off from it that make a significant impact to passage planning. Current is the foundation of the sea state here: specifically, streams current in close proximity that are running in opposite directions. This causes peaky waves of enhanced size. It can be really uncomfortable. This is similar to our experience in the Mozambique channel. There, too, the dominant current is conventionally described as monolithic – when actually, it’s much more complex.

Compounding the confused seas, we seemed to be doing a lot of unexpected upwind work. Routing algorithms indicated we could expect up to 25% to be upwind, but other than some gorgeous beam reaching the first day, the passage was almost entirely hard on the wind. And then, the wind was much stronger than expected forecast: instead of 20 knots (which we always always assume could be 40% higher, so, pushing up near 30 knots) we instead had a lot of mid-thirties, one especially uncomfortable night in the 40s, and top gusts around 50. Sailing into this wind, in sloppy seas, is cagetorically Not Fun. Recall that force=mass x acceleration, mix in square-fronted waves that are moving against us with the current, and it makes for uncomfortable pounding. Water sluices back along the side decks. Every imperfectly sealed hatch is found the hard way, and the girls’ bunk was soaked with saltwater. Leaks from the main cabin hatches make everything damp and salty.

The stress of these conditions cost us our kayak. We picked up the well-used Keowee from CraigsList back in… 2007, I think, or maybe it was 2006. It was a playground for the kids during that time at the dock while we worked getting Totem ready to leave. It was their first stretch of independence. It’s been our second car for years, the kids’ by default. My haven for solo exploration, or the nest for 1:1 time with one of the kids.

Niall and Mairen in our home port, Eagle Harbor…wearing jammies

It happened when one of these steep-fronted waves smacked into the bow for the Nth time. The kayak spends passages lashed to a couple of stanchions, and there was enough energy in motion for the broad, flat bottom of the kayak to exert significant force against the stanchions. One broke off at the base, loosening the lashing. A subsequent wave picked up the kayak and flung it over the lifelines, still attached to the boat and now banging on the hull while full of water. There was no safe option but to cut it loose, complete with paddles, fishing pole, dock hose, and more stored inside.

no more kayak; the broken forward stanchion is tied to its aft neighbor

This wasn’t even the worst chapter. Most frightening of all was in the wee hours of our third night at sea. Towards the end of my watch I caught the whiff of a faint odor; it got stronger when I went below, and seemed like smoke. I woke up Jamie, who has a gift for going from zonked to alert in seconds (not my specialty), and thank goodness for that, because it was apparent that something was burning and fire on board holds among the greatest potential for disaster. Jamie immediately went in action to suss out the source. Niall sees the lights on in the cabin, and although our teen is usually only up at 2:30a.m. if he hasn’t gone to bed yet, pops out to assist—getting out the life raft, putting it in the cockpit with our ditch kits, following us with fire extinguishers, doing whatever needs to be done. Tense minutes tick by searching for the source: engine, battery bank, charger, electrical panel check out. Finally, it’s found at the controller for the solar panel. This voltage regulator shorted internally, and the smell is from wires melting inside the unit. A breaker has already tripped, and likely prevented any further problem even if we hadn’t found it ourselves, but our hearts are pumping as Jamie disconnects the remaining wires.

last sunset at sea: no more ocean sunsets for a while

Chalked up to Neptune’s might: one kayak, one stanchion, one fancy big block, much salty laundry and cleaning to come. Some wet books, salvaged with careful drying. Not claimed: morale of the crew under tough conditions. The kids chipped in proactively, whether washing dishes or standing watch. Laughing and dealing instead of griping when the saltwater spray and leaks find their way, unwanted, into yet another corner of Totem. Acting quickly and as a team in an emergency. I am so proud of our crew. And I know we are all very grateful to put this passage behind us.

This wasn’t the dreamy voyage of night watch ruminations under a canopy of stars. It’s one we’re all happy to put behind us. Closing the miles towards Stonington, although I mourn the kayak, the energy on Totem isn’t mired in the difficulties of the past days. There is palpable excitement as we get closer to the “home” our kids have mostly learned about from afar, and the friends and family they recall through a few distant memories.

Totem is now tucked in at the Essex Yacht club for Summer Sailstice! Looking forward to a long weekend of good times and information sharing with the SSCA’s annual gam.