Humans have a really poor sense of smell, as anyone who hasn’t been living under a rock surely knows. It just takes a brief glance at the many animals we keep as pets to realise that our olfactory senses are pretty shabby. The police rely on sniffer dogs to identify illicit substances, not specially trained police officers. Whilst few smell receptors is pretty common amongst primates (who instead have better vision, which is more useful for swinging through trees), humans have few receptors even by monkey standards. Now new research by an international team of scientists have identified that this isn’t the result of chance but evolution is actually decreasing our sense of smell. What’s more it shows no signs of slowing down and it would seem we’ll continue to get worse at smelling into the foreseeable future.

Humans have a really poor sense of smell, as anyone who hasn’t been living under a rock surely knows. It just takes a brief glance at the many animals we keep as pets to realise that our olfactory senses are pretty shabby. The police rely on sniffer dogs to identify illicit substances, not specially trained police officers. Whilst few smell receptors is pretty common amongst primates (who instead have better vision, which is more useful for swinging through trees), humans have few receptors even by monkey standards. Now new research by an international team of scientists have identified that this isn’t the result of chance but evolution is actually decreasing our sense of smell. What’s more it shows no signs of slowing down and it would seem we’ll continue to get worse at smelling into the foreseeable future.

A blind cavefish along with their close relatives from lighter waters who have retained eyes

Natural selection is, after all, a two way street. The “fittest” organisms are more successful and reproduce more so subsequent generations will have a higher proportion of these fitter individuals. Eventually the vast majority of the population will possess the fitter traits, at which point they are said to be “fixed.” But fittest doesn’t always mean better. Indeed, creating an organism costs time and effort and if corners can be cut without sacrificing fitness then doing so will be the best tactic. That’s why many cave dwelling animals have lost their eyesight; it simply isn’t useful in the darkness and so the energy it takes to grow eyes would be better spent elsewhere.

This loss of function occurs via negative selection, which can happen through two mechanisms. First, if a trait is particularly detrimental then those who possess it will die or not be as successful at reproduction, gradually removing it from the gene pool. This process not only eliminates harmful traits but also harmful mutations. If an organism suffers from a genetic defect which stops a crucial body part developing then they are unlikely to survive so this mutation will not be passed on. As a result of this negative selection not only removes harmful traits but also keep the gene pool pure. Which brings us on to the second process. If this genetic defect damages a part of the body which is useless then the organism can still survive to pass on this trait, allowing it to spread through the population and sometimes rise to fixation by pure chance. Alternatively, if not developing the trait is beneficial because it reduces the cost of building and maintaining the organism then positive selection could also become involved.

When natural selection is relaxed it will allow deleterious mutations to survive

This second process is known as a “relaxation” of negative selection (since it simply doesn’t bother removing bad traits, which is quite laid back) and appears to be the process by which our sense of smell is getting poorer. An international team of scientists studied the genomes of 1,301 individuals and found that genes associated with our sense of smell had more deleterious mutations than natural selection should allow. These mutations would severely compromise our olfactory ability, rendering many of our smell receptors useless. With no evidence of positive selection for these detrimental mutations the team was forced to conclude that this is a result of the relaxation of negative selection. Damaging our olfactory ability does not harm our chances of survival so they survive to be passed on.

Further, the researchers noted that the relaxed negative selection shows no signs of “tightening” and that we have not reached the point where these changes start to eat into our ability to survive. In other words, our sense of smell can continue to get worse and negative selection will still do nothing about it. Our sense of smell will continue to deteriorate. The researchers postulate that natural selection tolerates this “devolution” because our sense of smell isn’t as useful as it used to be. As I already mentioned, apes have focused more on their visual ability to better travel through trees. On top of that, we’re now bipedal and so our nose is a lot further from the ground than it used to be. We aren’t going to be smelling much up here.

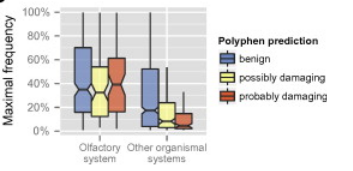

The olfactory system has more damaging mutations than other senses

But it’s not all doom and gloom, other researchers disagree with this conclusion. Our decrease in smell receptors has been known about for a long time but some scientists believe that this is compensated for by improvements in our brain. After all, our brain – including the bits responsible for smell – has more than tripled in size since our lineage diverged from the rest of the apes and this could well have enabled us to continue to smell quite well. Unfortunately there’s little evidence that this is the case and it remains a hypothesis. As far as we know our sense of smell has gotten worse and it would appear that it will continue to do so.

My one qualm with their study is that their conclusion about whether a particular mutation is damaging is based off various computer predictions. With my limited understanding of genetics I can’t really say if this is a good or a bad thing, but it does open up the possibility that they may be wrong. However, from what I can gather this does seem to be a fairly common and reliable practice. So it would seem this one concern does not overturn their results. Our sense of smell is indeed devolving and will likely continue to do so.

Pierron D, Cortés NG, Letellier T, & Grossman LI (2012). Current relaxation of selection on the human genome: Tolerance of deleterious mutations on olfactory receptors. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution PMID: 22906809