by Paul J. Pelkonen

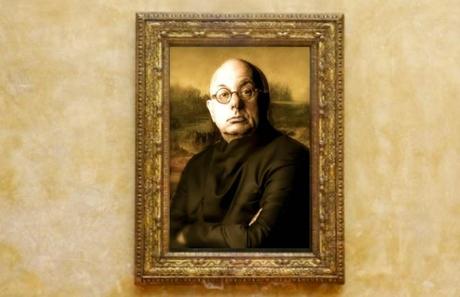

American Symphony Orchestra music director Leon Botstein visits the Louvre.

With apologies to Leonoardo Da Vinci. Original photo by Ric Kelleher.

Photo alteration by the author.

There is perhaps a certain historic justice in Schillings' fall into obscurity. Mona Lisa was his fourth (and final opera) before the composer dedicated himself to conducting, teaching and administration. In 1932, he took over the Prussian Academy of the Arts, and was directly responsible for dismissing both Arnold Schoenberg and Franz Schreker from the teaching staff of that Berlin school. This unpleasant character, a self-declared anti-Semite, died just six months after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany. Following the fall of the Third Reich in 1945 he was largely forgotten.

The smoky, chromatic perfume of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde hangs heavily over Mona Lisa. Schillings draws freely from that much better opera, couching his own dramatic love triangle of a jewelry-obsessed nobleman, his straying wife, and another fellow who attracts her during the Carnival season. The end result is like Ponchielli's La Gioconda without that work's melodic inspiration or marvelous title role. Later sections borrow from Parsifal (the Ash Wednesday music at the start of the second act) and Richard Strauss' Elektra, the climactic scene where the title character takes her well-deserved revenge.

The libretto (by the playwright Beatrice Dovsky) is a fiction, a thriller that owes more to Dan Brown than to Da Vinci. A Prologue shows a rich foreign couple visiting the palace where Mona Lisa and her husband, Francesco del Giocondo lived. Their guide, a Lay Brother (tenor Paul McNamara) tells them some of the sad story before the opera time-travels back to the Renaissance and unveils the truth behind the Mona Lisa's smile The couple are the same singers who play out the tragedy of Lisa and Francesco, and the Lay Brother doubles the role of Giovanni, the young rake who comes between them and is eventually murdered by the husband.

The proto-Straussian soprano role is demanding, with the singer having to display soft colors in the opening scene and ranging up to full-throated hochdramatische singing at the climax of the work. German soprano Petra Maria Schnitzer sang with a bright, steely tone throughout. Confined by the concert format and the proximity of her music stand, the statuesque singer did her best to emote with her hands but did not put the same effort into her voice, until the punishing final scene where Mona Lisa kills her husband. Here, she simply opened up and went for it, providing plenty of volume but less precision of pitch.

Mr. McNamara had a strong instrument, starting in the baritonal register before opening up the upper notes in the role of Giovanni. A mature singer, Mr. McNamara still conveyed passion and youthful ardor in the big Act I love duet. His character's death was well-handled, with the singer going offstage and conveying the sounds of suffocating to death inside a large jewelry cabinet. (At least the librettist gets credit for an inventive operatic death.)

More problematic was the young bass-baritone Michael Anthony McGee as Francesco. The Texas native proved to have a lightish, high-lying instrument that narrated the text but did not convey a low register or any sense of menace. That said, he was good at conveying seething jealousy and ultimately psychotic rage, and worked well in the duos and trios that make up the bulk of the long first act. His death (again in that cabinet with no mention of what had happened to the first corpse) provided the opera with a most satisfying conclusion. It was accompanied by liturgical chanting, an idea cribbed from Il Trovatore.

There were some good singers in supporting parts. As Arrigo, tenor Robert Chafin has a big, sweet voice and a stage presence to match in the secondary role. Soprano Lucy Fitzgibbon was strong as Dianora, the daughter of Giocondo whose chief function is to return the cabinet key to Lisa after her husband throws it in the Arno. The remaining cast and the Bard Festival Chorale (under the direction of James Bagwell) captured the energy of the opening scenes, where Schillings tries to depict the fever of Florence at Carnival in the turbulent year of 1492. The American Symphony Orchestra seemed to relish playing this colorful score, which includes bits of Puccini (the tolling chords from the end of Act II of Tosca), presumably added to give an Italianate feeling to this heavy Germanic music.