by Paul J. Pelkonen

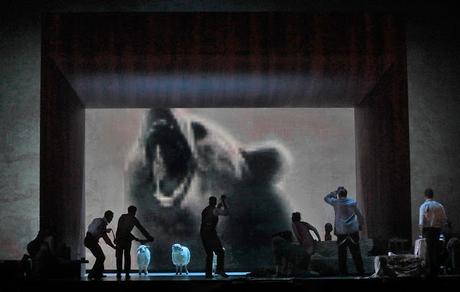

Ursa Major: the cast of The Exterminating Angel (and two sheep) confront the unthinkable in Thomas Adés' opera.

Photo by Ken Howard © 2017 The Metropolitan Opera.

This opera opened last Thursday, the second of Mr. Adés' stage works to be presented at the Met. (It was was seen by this critic, from a rush seat, at the Met's second performance on Monday night.) For his opera, Mr. Adés and librettist Tom Cairns adapted El Angel Exterminador, the surreal 1963 film by Luis Buñuel. The opera (the production is by Mr. Cairns) starts imperceptibly. Before the house lights go down, bells chime from the orchestra pit. A projection of palm trees, headlights and city streets appear on the black scrim curtain. And then suddenly one is immersed in the sound-world of this opera, an endless and inventive score under the baton of Mr. Adés himself.

In short, this is the story of a high society dinner party that goes horribly awry. Elites rub elbows with an opera singer, a pianist and a venerable doctor. Somebody brings a circus bear on a leash (shades of Siegfried!) and there are also sheep loose in the house. The human guests snipe at each other, and then they discover that none of them can leave the drawing-room. The food quickly runs out. Starving, scared and exhausted, these folks must endure each others' company far longer than they would like. (In other words, this is every New Yorker's nightmare, writ large.)

Clad in evening gowns and formal wear, the cast spend most of this show underneath an enormous square arch that moves slowly and majestically on the Met's 50-year-old turntable. The arch is a symbol of their confinement, an oppressive structure that looms overhead, dwarfing the singers. For three acts, the singers have to battle Mr. Adés' two-fisted orchestration, which includes heavy brass and percussion, complicated writing for winds and the ondes Martenot. Mr. Adés' writing is claustrophobic, using his vaunted technique of slab-like chords and heavy orchestration to enhance the feeling of confinement and gloom. However there are rays of sunshine in the thick web of sound and witty references including one to the composer himself.

The first act is mostly setup. A cast of servants appears, chatters and (as in Strauss' Elektra) becomes quickly irrelevant. Mr. Adés and Mr. Cairns give the ear and imagination a lot to process in the first hour and a half. A sense of confinement permeates every bar. As their situation becomes clear, these glittering characters slowly lose their sanity and humanity. They become debased, pressed, suicidal, and ultimately violent. With three exceptions, most of them survive, but the experience of their confinement is shattering to witness.

The third act is hard to watch too, but easier to process. As the surviving characters wake up, things go downhill fast. Although the partygoers punch a hole in the floor to get water. One of the sheep is killed in the opera's most effective moment, its grisly Straussian murder pounded out by the orchestra, which dies into sickening silence. The survivors feed themselves by roasting said sheep over a primitive fire (fueled by burnt and broken musical instruments.) However, their paranoia and tension is at a peak. The Doctor struggles to maintain order, but the more spiritually crazed guests start planning some kind of weird religious sacrifice. This is thankfully stopped in its tracks.

The Met has spared no expense on a lavish cast. The parade of names is led by Alice Coote, a veteran of this kind of modern opera. Other notable voices include baritone Rod Gilfry, soprano Amanda Eschalez (as Leonora, the evening's hostess) and the veteran British bass Sir John Tomlinson as her doctor. Soprano Sally Matthews and countertenor Iestyn Davies play a pair of incestuous siblings. Another pair of lovers: Beatriz (Sophia Bevan) and Eduardo (David Portillo) get an amazing scene together: a compression of Tristan und Isolde with similar, tragic results.

Mr. Adés saves his final peroration for Leticia, played by super-soprano Audrey Luna. Her small, stratospheric voice keeps going up and up in the work's climax: to the point where one wonders if the composer is writing for a canine audience. The altissimo register makes the text sound garbled when clarity is essential, and the piping sound quickly wears out its welcome. This exuberant moment is followed by a final chorus, in which the entire cast and chorus are hemmed in by the oppressive archway. One wonders if this was a trailer for a sequel: Exterminator 2: Judgment Day?