by Paul J. Pelkonen

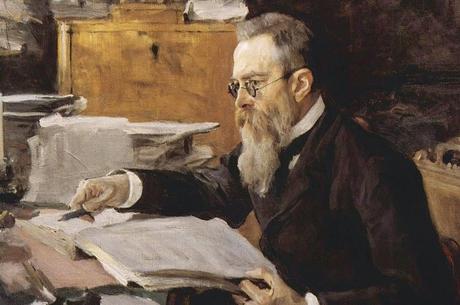

The composer of The Tsar's Bride,Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov in a portrait by Valentin Serov.

In Russia, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's 1898 opera The Tsar's Bride is one of his most popular works. However, it is a relative rarity in the United States, and has never been mounted by the Metropolitan Opera. Upon hearing the score, this is a surprise, because this opera, retelling a heavily fictionalized episode in the tumultuous love life of Russian tsar Ivan the Terrible combines the romantic sweep and Russian folk-colorization of Rimsky's best music with a libretto that might have appealed to Giuseppe Verdi.On July 13, the Bolshoi Opera gave the second of two weekend concert performances of The Tsar's Bride as part of this summer's Lincoln Center Festival. The concert, led by veteran Russian conductor Gennadi Rozhdestvensky drew a large and enthusiastic audience of Russian opera lovers, but lacked certain elements of energy and theatrical excitement. It didn't help that this vivid and bloody story was confined to the concert stage, with the drab wooden walls of Avery Fisher Hall a poor substitute for the color and pageantry that are integral to this work.

Mr. Rozhdestvensky is in his 80s, and his long career dates back to the days of Stalin. The conductor spun out some glorious musical phrases, allowing the audience to experience the dark and distinctly Russian sound of the fine Bolshoi players, but robbed the music of much of its momentum and rhythmic drive. With its poisonings, persecutions and the constantly hovering (but never seen) threat of Ivan himself, this can be a thrilling night at the theater, but Sunday's performance felt by-the-numbers.

This Festival marked the Bolshoi's first New York appearances in almost a decade, and its orchestra and chorus remain top-flight. The string players painted gorgeous rainbows of sound, illustrating Rimsky's mastery of orchestration with every detailed phrase. The (mostly male) chorus lent terrifying weight to the Oprichniki, the hooded, masked secret police that were Ivan's most dreaded underlings, giving a whiff of the fear that permeated Russia in the second half of the tsar's reign. They even get an anachronistic and rousing chorus at the end of Act II, where one hopes that the composer was writing from an ironic perspective.

The unlucky girl getting married off to Ivan is Marfa, a sweet innocent who becomes the focus of political machinations. Soprano Olga Kulchinskaya gave an eye-opening performance, despite the fact that her character does not show up until Act II. She demonstrated a sweet, lyric instrument, emphasizing her character's innocent nature. She glided expertly over the lush orchestration, singing with great beauty of tine and pathos in her Act IV death scene.

As Lyubsha, the operas jealous, scheming second lead (and its best role) mezzo Svetlana Shilova was riveting. Her Act I revenge aria wears the Verdi influence proudly on its sleeve, and her scheming scenes with in her act I revenge aria and in her scenes with the oprichnik Grigory Gryaznoy (baritine Alexander Kasiyanov) the plotters recalled that composer's portrait of the Macbeths. Their big duets, expertly supported by Mr. Rozhdestvensky were where this opera really took off. On his own though, Mr, Kasiyanov was somewhat dry of tone, and therefore less interesting.

Tenor Bogdan Volkov was compelling in the largely thankless role of Lykov, the boyar whose love for Marfa gets pushed aside by Ivan. Bass Nikolai Kazansky was deep and firm as Skuratov, and Alexandra Chukhina shone in the supporting role of Dunyasha, Marfa's friend and rival for Ivan's hand in arranged marriage. The best bit of casting was the veteran Irina Udalova in the small role of Domna Saburova. Ms. Udalova is a veteran of this opera, having sung both Marfa and Lyubusha in a long stage career and her presence was a welcome bit of luxury casting.