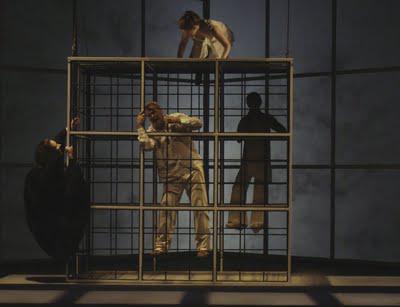

Cage match: A scene from Act Two of Phaedra.

Photo by Katherine Elliot, © 2011 Opera Company of Philadelphia

The story is based on Euripides' treatment of the Phaedra myth. Phaedra is the wife of Theseus, the Athenian hero best known for slaying the Minotaur in the Labyrinth of Knossos. The opera opens with the death of the beast. Things take a sharply personal turn as Phaedra falls in love with her step-son Hippolyte, an illicit affair that results in disaster and the latter's death.

Henze originally stopped there, but real life led to the creation of a second act. In 2005, the composer was struck with a mysterious illness and fell into a coma for two months. Upon reviving, he worked with librettist Christian Lehnert to provide a second act and create a scenario in which Hippolyte is resurrected and crowned as king of the forests by the goddess Artemis. The final result was a 75-minute opera in two acts, performed here without an intermission.

The score of Phaedra owes much to Richard Strauss' late style and the 12-tone writing of Alban Berg. Henze makes use of a powerful brass and wind sectin in his score, supporting them with an elaborate percussion section and minimal strings. Tuned keyboard instruments are featured alongside "found" sounds, including the recording of a buzz-saw and what might be the first cellular phone ever used in an opera. Unusual amplification of instruments like the harp provide dense, otherworldly textures, a fitting background to the fantastical plot.

This work proved potent in performance. Mezzo-soprano Tamara Mumford (Flosshilde in the Met's new Das Rheingold) brought physical and vocal athleticism to the title role. Heroic tenor William Burden was compelling as the dead-then-resurrected Hippolyte, the object of his step-mom's obsession. The hunt goddess Artemis was subject to some gender-bending, with countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo singing the part. Mr. Costanzo's performance combined impressive vocal gyrations with a fierce dramatic heart. Finally, Elizabeth Reiter was impressive in the small role of Aphrodite, singing her duet with Phaedra to Hippolyte as he was trapped in a cage.

If Phaedra sounds like heady, pretentious stuff, it is. But it also the latest in a long operatic tradition of putting fresh spins on familiar mythology, one that stretches from Monteverdi's Orfeo, through the operas of Handel, Haydn and Mozart to the late stage works of Richard Strauss (Daphne and Das Liebe der Danaë.) At this late state in his career, the octegenarian Henze makes his case as an important composer of opera, a visionary whose work can still compel and thrill the adventurous listener.