Clary leaves after washing and drying

Throughout the course of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a number of authors produced books called The Complete Confectioner, or with a title that was a variation on this name, such as The New, Universal and Complete Confectioner. The earliest book with this name was a newly christened edition of Mary Eale's Receipts (first published 1718), renamed The Compleat Confectioner, or the Art of Candying and Preserving in the Utmost Perfection (London: 1733). This was followed in c.1760 by Hannah Glasse's The Compleat Confectioner, which was very cheekily plagiarised in the 1780s by the publisher Alex Hogg, though he changed the title to The New, Universal and Complete Confectioner to disguise its source. The text is identical to Glasse's book, though it was issued under the name of a fictitious author called Elizabeth Price.

In 1789, the professional London confectioner and cook Frederick Nutt issued another Complete Confectioner, though this appeared anonymously in its first two editions under the authorship of 'A Person'. In 1800 a curious volume was issued by an author called Maria Wilson with the same title. She proclaimed on the title page that her book was actually by Mrs Glasse 'with considerable additions and corrections, by Maria Wilson'. Finally, in 1809 the Edinburgh confectioner J. Caird issued his Complete Confectioner, which of all the books with this title is my very favourite. Caird's D'Arcy Cream, an ice cream flavoured with marmalade is to die for. Like Nutt's book, Caird's is an entirely original work. Unfortunately this cannot be said of Maria Wilson's additions to Glasse's The Complete Confectioner, as she lifted all of her extra recipes directly from another confectionery manual called The Court and Country Confectioner by a Mr Borella, which was published in c.1770. Although she credits Mrs Glasse, Wilson makes no reference to Mr Borella whatsoever. This dishonest state of affairs, with its unscrupulous borrowings, is fairly typical of the highly dodgy publishing scene of this period. Since Mrs Wilson cheated Borella of any credit, I thought I would set the record straight by giving you one of his recipes which she claims as her own in her additions to Glasse's book.

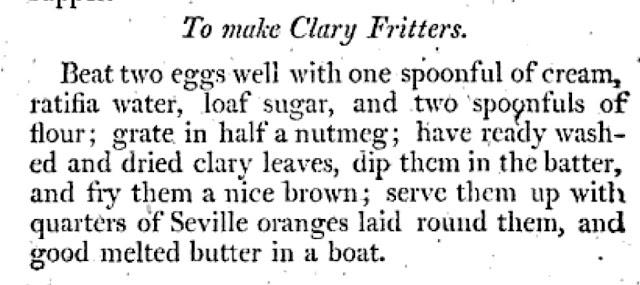

Borella, who tells us the had been confectioner to the Spanish Ambassador in London, gives us some outstanding recipes. His Muscadine Ice, a lemon water ice flavoured with elderflowers was probably meant to simulate the flavour of Muscatel grapes. He also suggests a variation which includes white currant juice, which I think is one of the greatest water ices ever. Another recipe with a connection to muscatel grapes is an interesting one for clary fritters. Clary or Clear Eye (Salvia sclera L.) is a member of the Labiatae closely related to sage. Its fragrant essential oil has a muscatel scent and it was used to flavour wines to give them a musky character. In my experience of growing the herb, the scent of individual plants can vary from being odourless, to pleasantly musky, to strongly redolent of cat pee. To make the fritters, Borella tells us to dip the clary leaves in a nutmeg flavoured batter with eggs, water, sugar, cream, flour and ratafia water. By the latter he meant an almond flavoured liqueur which was rather similar to amaretto, which you could use today as a substitute. Here is the recipe.

The large leaves dipped in batter and fried in hog's lard look like fillets of sole or other flat fish

The finished fritters dusted with sugar and with their garnish of orange slices

The acidic juice of Seville orange makes a great foil to these lovely fritters, which have a lovely hint of bitter almonds from the ratafia water in the batter mix. Recipes for clary fritters go back a long way and were not just confined to the English kitchen. Taillevent (c.1310-1395) in Le Viandier gives us a recipe for fritelles made from a purée of clary leaves, honey, white wine and flour. The fritelles were fried and then dressed with sugar and rosemary. In medicine, clary was used for treating eye problems, but it also had other applications, one being as a form of early modern period viagra. In The English Physician (London: 1652), the astrologer and herbalist Nicholas Culpepper tells us, 'the seeds or leaves taken in wine, provoketh to venery... the juice of the herb in ale or beer, and drank, promotes the courses.' Culpepper's sixteenth century predecessor John Gerard in his Herball, or Historie of Plantes (London: 1597) explains that clary was used in making a type of fried tanzie, an Elizabethan cross between a pancake and an omelette.

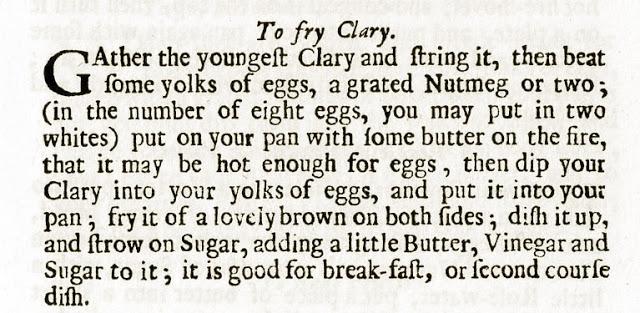

This recipe for fried clary leaves from William Rabisha, The Whole Body of Cookery Dissected (London: 1661) suggests it could be served as a breakfast dish. His tip to remove the tough strings from the main leaf vein is very sensible

Clarie from John Gerard The Herbal or Historie of Plantes (London: 1597).