Visitors to my kitchen frequently remark on the large number of antique jelly moulds scattered around the room. I usually explain that just a few of them were actually used for turning out jellies and even some of those had other uses. For instance, on the kitchen dresser in the photo above there are moulds for making puddings, ice compotes, nougat compotes, nougat cornucopias, chocolate peacocks, raised pies, sugar baskets, cakes and ice cream bombes. There are also some jelly moulds, but they are in a minority. "All that glitters is not gold" and all that is shiny copper is not necessarily a jelly mold.

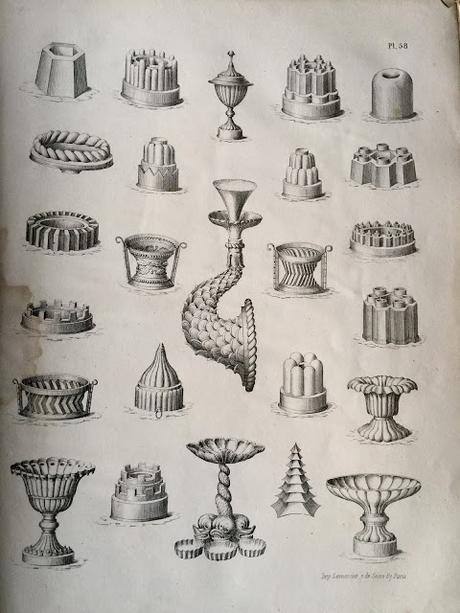

This advertisement for culinary moulds produced by the Paris firm Trottier in the 1860s testifies to the remarkable variety of moulds available for kitchen and confectionery use at this period.

It is actually a size thing. Nineteenth century copper moulds for jelly are rarely over five inches high. The highest they were ever made was six and a half inches and that was pushing it a bit. This is for a very simple reason. Any taller than this and the jelly will split and collapse, especially if of a light set. Of course it is possible to make taller jellies, but an inordinate amount of gelling agent has to be used, making them rubbery and unpleasant to eat. More stable jellies could be made in the taller moulds when fruit (or even profiteroles) were enclosed in the gel. These additions strengthened the jelly by creating what I guess could be called an edible, internal armature. Most moulds over five and a half inches were probably designed for this particular purpose.

This late nineteenth century advertisement clearly illustrates the range of mold heights for jelly moulds. Those in the six and a half inch high category were probably designed for being filled with fruit to make the finished jelly more stable.

One specialist six-inch tall mold for making a jelly with a fruit macedoine core came provided with a separate internal liner in the form of a dome. This created a cavity within a cortex of transparent jelly, which would be filled with a macedoine of fruit. A jelly made in the outer mold alone is terribly unstable. It usually splits and dramatically collapses within a few seconds. Some taller moulds were designed to hold other specialist liners, such as the taller versions of the Belgrave, Alexandria and Brunswick Star. When set, these all had internal blancmange 'armatures' which gave them a degree of stability and helped them hold together.

A lesson in size - the small four inch tall mold on the right is a typical size for a jelly mold. The second mold from the right (nine inches high) is not a jelly mould, but a cake mold used for turning out Savoy or Baba cakes. The two six inch high moulds on the left are both macedoine moulds with an inner liner to create a cavity, which can be filled with fruit.

Perhaps the most spectacular of all Victorian jellies. The Macededoine Jelly in the foreground was made with one of the moulds illustrated in the previous photograph. While the Belgrave Jelly behind it was made with the mold below. These internal structures lent a stability to the jelly.

Mould and liner for the mysterious Belgrave Jelly illustrated above.

The famous Alexandria Cross mold as illustrated in the Marshall advertisement above was made in three sizes - six and a half inches, four and a half inches and three inches. The mold on its side with liner inside is the tall six and a half inch version. At this marginal height it takes a great deal of skill to make it with a decent light jelly set so that it is edible and holds together on the plate. The little three inch Alexandria Cross is extremely rare.

Some of the taller moulds were designed with other purposes in mind - not just for jellies. For instance, some savoury dishes, like the pain de gibier in the image below, were strong enough to be de-moulded without collapsing, as they were based on a firm and quite solid purée of meat held together with isinglass. Because of their solid consistency dishes of this kind were more difficult to get out of the mold than a much more pliant jelly, but a skilled cook of the nineteenth century would have had few problems doing this.

A recreation of a Waterloo banquet from 1839, which I produced for the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo at Apsley House in 2015. The magnificent Portuguese service is in the middle of the table. My food is on serving dishes gifted to the Duke of Wellington by the Kaiser of Prussia. The pain de gibier à la gelée made from a Câreme recipe on the far left, sits on an ornamental wax socle and is garnished with hatalet skewers of truffles and turned mushrooms.

All this goes to show that nineteenth century moulds were desigeed for a complex and flexible cuisine, which has been mainly forgotten. Modern chefs are not taught how to use what is now considered to be obsolete equipment. The English TV production company Wall to Wall, who specialise in living history programmes, recently featured a very large copper mold in two different programmes, with predictably disastrous results. In one of the programmes, The Victorian Bakers at Christmas, which I have already mentioned in a previous article, the mold was used to boil a plum pudding. I could tell when I watched the mold being filled with pudding mixture that this was just not going to work. Not because the mold was too large in this case, but it was not thoroughly greased and the mixture was too slack. I took some screen shots to show you what happened.

This very large and quite spectacular castle mold has a wired rim and a hanging ring, so I am sure it is French. It was probably designed for turning out a pain de gibier à la gelée or similar savoury dish. Its design is too fussy for a Savoy Cake or Baba, though with care it could be used for those. In this case it is being used to boil an English plum pudding - possible, but risky,

The pudding refuses to come out in one piece. It is likely that the top of the pudding either burnt to the mould, or the mold was just not greased thoroughly. Victorian cooks would have chosen a simpler mold.

The rest of the pudding remains in the mold - embarrassing

The very same mold turned up a few weeks later in Wall to Wall's BBC production Back in Time for Dinner presented by Giles Coren and the excellent food historian Polly Russell from the British Library. The hard-pressed chef who made a valiant job of cooking food for the family was provided with the same totally inappropriate mold for turning out a jelly. Again in the screen shots below you can see the result - a predictable failure and not the fault of the cook. If the chef had been given a sensible-sized mold designed for jelly, I am sure she would have produced an attractive dish. But I guess these failures are perceived by the producers as making better television. I personally think it is misguided and unfair to the cook. Perhaps we will see the 'Jonah mould' again soon - I gather Wall to Wall are making a programme on the history of confectionery - third time lucky!

Oh no! It is that same Jonah mold again - you can gauge its huge size - being used in another Wall to Wall production for BBC- Back in Time for Dinner. This time to turn out a jelly. Not wise!

The jelly fails because of the totally inappropriate choice of mold.