Orchis italica - a possible candiate for the satyrion of antiquity?

In my last two posts I described some historical food items with mild sexual links - a chocolate cockerel covering its hen and a rather suggestive jelly which wobbled in a lascivious way. These novelty items were conceived purely for the amusement of the diners, but there has always been a more serious link between certain foods and carnality. No more so than when they were employed as aphrodisiacs. Oysters are famous for their alleged properties in this regard, but a number of other less well known esculents were also thought to possess the power to stir up lust. Classical writers on medicine, such as Dioscorides and Pliny described a number of plants which were famed in antiquity as powerful aphrodisiacs. The most notorious of these were various kinds of orchid. In Greek orchis means 'testicle', because a number of them have two underground tubers which resemble these male organs. Some like Orchis italica (images above and below) also have astonishingly convincing anthropomorphic flowers, although it was the testis-like tubers that were considered to be efficacious as a sexual stimulant.

Orchis italica. Woodcut from John Parkinson, Theatrum Botanicum. (London: 1640).The individual flowers of this Mediterranean orchid have an extraordinary resemblance to miniature well-endowed satyrs. Together with the two testis-like tubers this feature must have led early physicians to believe that plants of this kind could be used as love potions. Parkinson and his colleagues called this group of orchids 'fooles stones' because of the resemblance of the three upper lobes of the flower to a large fool's or jester's hat. This is strongly evident in the photograph below.

Caption anybody? What about 'My ears are bigger than your ears'?

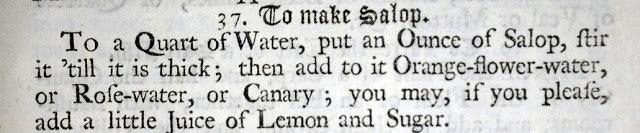

It is easy to understand why these curious physical features led early physicians to conclude that the creator had designed these herbs as sexual stimulants. Various orchid species are still harvested for their tubers, which are used in the Middle East to make a beverage known as salep. This warm comforting drink is still considered by some to have sexually provocative properties. When I lived in Athens in the 1970s I remember the street cry of the salep vendor, 'Salepi zesta! Salepi zesta!' - 'Hot salep! Hot salep!' Their customers were always male, quickly downing small cups of this gelatinous beverage on the street before they headed home to their wives. In his seminal work on materia medica, A Complete History of Drugs (London: 1747), the great French botanist Pierre Pomet tells us. 'It is a great Restorative, and is good in all Decays; it is also esteemed a Provocative and Remedy againft Barrenness. The Turks have it in great esteem; their manner of taking it is boiled with Honey, Ambergrise, and Ginger, and drank hot in the manner of Chocolate. The general manner of using it here, is to put about a Tea-spoonfull of the Powder of it into a Bason of warm Water, which it turns into a Jelly.'Salep, sometimes spelt salop, was available from the seventeenth century onwards in English coffee houses, together with other fashionable Ottoman beverages such as coffee and sherbet. It would appear that in Britain, the orchid tubers and the flour-like powder ground from them was mainly imported from the Levant. Salep is still popular in the Middle East as a drink, but is used much more nowadays as an ice cream ingredient. In Turkey it is still harvested from a number of wild orchids, some of which are facing extinction because of the enormous quantity used in the ice cream industry. This is based mainly in the city of Kahramanmaraş near the Syrian border. The thick salep ice cream, known locally as Maraş dövme dondurması does not melt as easily as ordinary ice cream and is incredibly elastic, stretching almost like putty. It is still made by some vendors using the traditional ice pail, sorbetiere and spaddle. Its amazing viscosity and ability to stretch has made the Maraş stalls in tourist destinations such as Istanbul very popular. It is the addition of salep flour and mastic to the ice cream mixture that gives it its extraordinary viscosity.

A recipe to make salep from John Nott, The Cook's and Comfectioner's Dictionary (London: 1723)

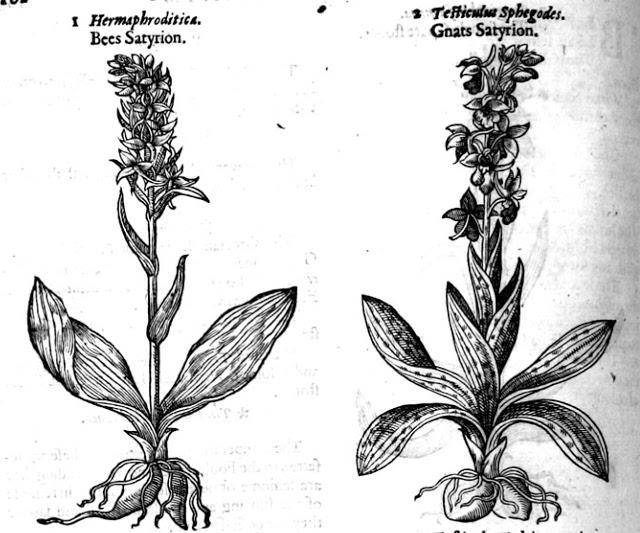

The most allegedly potent of all the plants from antiquity used as an aphrodisiac was known as satyrion, first described by the Greek physician Dioscorides in the 1st century AD. Its exact identity will probably never be known. Many of the English herbalists and botanists of the early modern period assumed that satyrion was a kind of orchid. In fact they called a number of English orchid species by this name. The celebrated Elizabethan plantsman and herbalist John Gerard describes a number, including Bee's Satyrion and Gnat's Satyrion. His rival John Parkinson, 'herbarist' to James II on the other hand believed that the original satyrion of Dioscorides was not an orchid, but a species of tulip.

Two Satyrion varieties from John Gerarde, The Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes . (London: 1597).

However, the historical evidence points to the fact that the satyrion roots sold by English apothecaries were most usually the tubers of the common spotted orchid Orchis mascula. Elizabeth Blackwell, in A Curious Herbal (London: 1751) describes this plant. She tells us,

'This Orchis, which is the common Satyrion of the shops, grows to be a foot high; the leaves are a bright green, spotted with black, and the flowers, which grow on a brownish stalk, are a red purple. It grows in moist meadows, and flowers in April and May. The roots are accounted a Stimulus to Venery, strengthening the Genital Parts and helping Conception; and for these Purposes are a chief ingredient in the Electuarium Diasatyrium. Outwardly they are applied in form of a cataplasm, and are esteemed good to dissolve hard Tumours and Swellings. The officinal preparation is the Electuarium Diasatyrium.'

Orchis mascula. The common spotted orchid from John Gerarde, The Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes . (London: 1597). Though not the original satyrion of Dioscorides, this plant was the one used in England to make the aphrodisiac of that name.

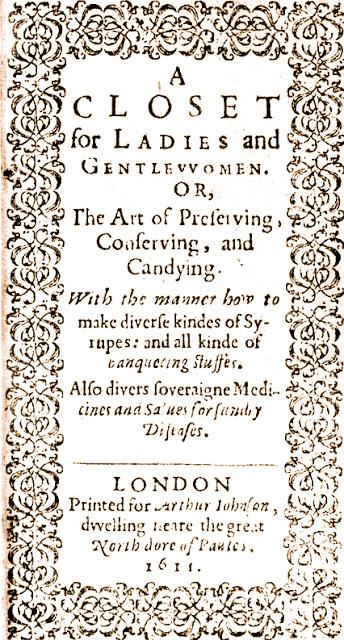

In England Orchis mascula tubers were preserved in sugar syrup. There is a very early recipe for preparing them in this way in A Closet for Ladies and Gentlewomen, a little book of recipes for preserves, 'banqueting stuffes' and medicines, first published in London in 1608. Its title declares that its intended readership was the female sex, more specifically high status ladies and gentlewomen. So here was a recipe for an early homemade viagra for those ladies whose noble husbands were not living up to expectations in the venery department.

A later edition of A Closet for Ladies and Gentlewomen. This tiny book went through many editions and was often bound in with Sir Hugh Plat's Delightes for Ladies.

Here is the recipe

To preserve satyrion roots

Take your saterion roots and pick out the faire ones and keep them by themselves, then wash them and boyle them upon a gentle fire, as tender as a Quodling, then take them off and pare the blackest skin of then, and put them as you pare them into fair water, and so let them remain one night; and then weigh them, and to every pound of roots, you must take eleven ounces of clarified Sugar, and boyle it almost to the height of a sirup, and then put in your roots, but take heed they do not boyle too long, for then they will grow hard and tough: and therefore when they bee boyled enough, take them off, and set them a cooling, and so keep them according to the rest.

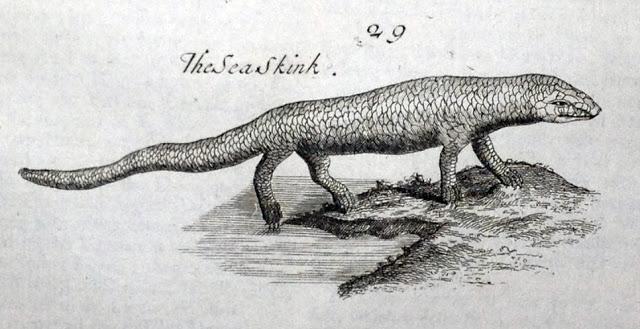

In some editions of the work, satyrion crops up as an ingredient in the complex 'restorative' marmalade described in the recipe below. This eccentric marmalade contains a host of other substances believed to be aphrodisiacs, including cock's testicles, cantharides, pearls and both the belly and back of the sand lizard Scincus scincus, described in the recipe incorrectly as a fish.

A foor legged scaly version of Levitra. These amphibious lizards were imported in dried form from Egypt. From Pierre Pomet, A Complete History of Drugs. (London: 1748)

'To make another sort of Marmelade very comfortable and restorative for any Lord or Lady whatsoever.Take of the purest greene Ginger, sixe drammes, of Eringus and Saterion rootes, of each an ounce and a halfe, beate these very finely, and draw them with a siluer spoone thorow a haire searse, take of nut kirnells and almonds blaunched, of each an ounce, Cockes stones halfe an ounce, all steeped in hony twelve houres, and then boyled in milke, and beaten and mixed with the rest, then pouder the seedes of redde nettles, of rocket of each one dramme, Plantane seeds halfe a dramme, of the belly and backe of a fish called Scincus marinus three drammes, of Diasaterion foure ounces, of Cantarides adde a dram, beate these very finely, and with the other powder mixe it, and so with a pound of fine suger dissolued in rose water, and boyled to suger againe, mingle the powder and all the reſt of the things, putting in of leafe golde sixe leaues, of pearle prepared two drammes, oyle of Cynnamon sixe drops, and being thus done and well dryed, put it up in your Marmelate boxes, and guild it, and so use it at your pleasure.'

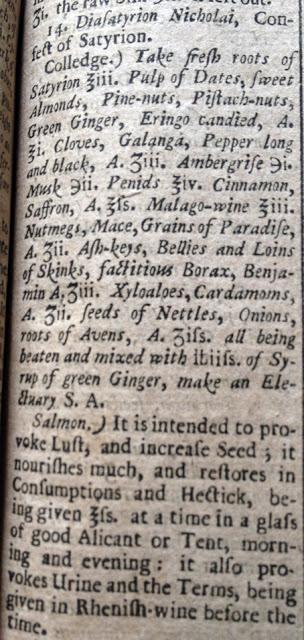

The ingredient referred to as Diasaterion was in fact itself a compound medicine made in the form of a confect or electuary. It actually duplicated a number of the ingredients already added to the marmalade, such as satyrion itself, eryngo and even more generous helpings of the skink lizard. The recipe below for Diasatyrion is from William Salmon, Pharmacopoeia Londinensis, Or The New London Dispensatory (London: 1682)

As well as the satyrion itself, the other important ingredient with alleged aphrodisiacal properties in both the restorative marmalade and Diasatyrion was candied eryngo root. This was made from the roots of the common sea holly (Eryngium maritinum). I have already written at length about Eryngo in an essay in the journal Petits Propos Culinaires, particularly about its long association with the town of Colchester in Essex where it was once produced as an article of commerce.*

Eryngium maritimum or Sea Holly. The candied roots of this plant were once considered to be a powerful aphrodisiacs

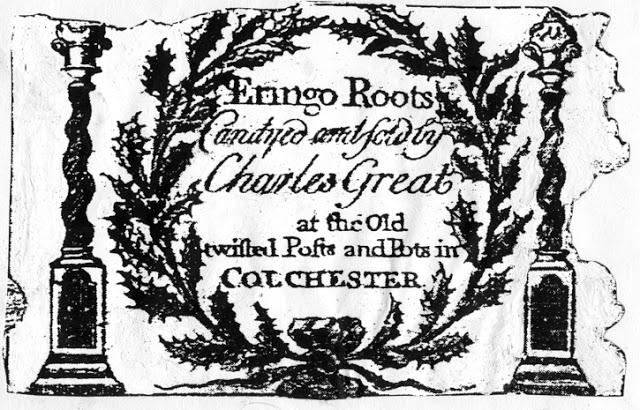

At the Holly Trees Museum in Colchester there is a surviving box of eryngo roots dating from the eighteenth century complete with its lusty contents. If these little sweeties were the viagra of the early modern period, they were sent out all over Britain by the Pzifer of the day, the apothecary Charles Great, who traded them from his shop at The Sign of the Old Twisted Posts and Pots. The label on one of Great's eryngo boxes is reproduced below.

Courtesy of Holly Trees Museum

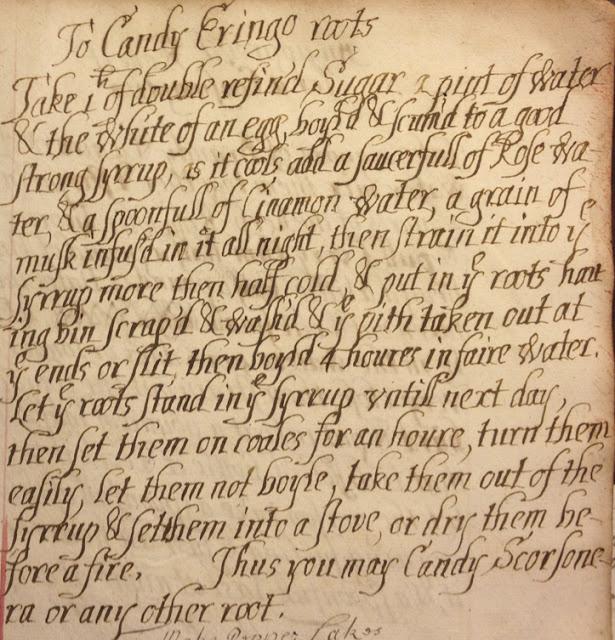

Many recipes for preserving eryngo roots survive in both manuscript and printed sources. The handwritten recipe below is from the manuscript receipt book of Elizabeth Rainbow, wife to Edward Rainbow, Bishop of Carlisle in the late seventeenth century.

A late seventeenth century manuscript recipe to candy eryngo roots from The Receipt Book of Elizabeth Rainbow. Courtesy Dalemain Estates

Some of my candied eryngo roots. They have a subtle flavour halfway between a parsnip and a chestnut

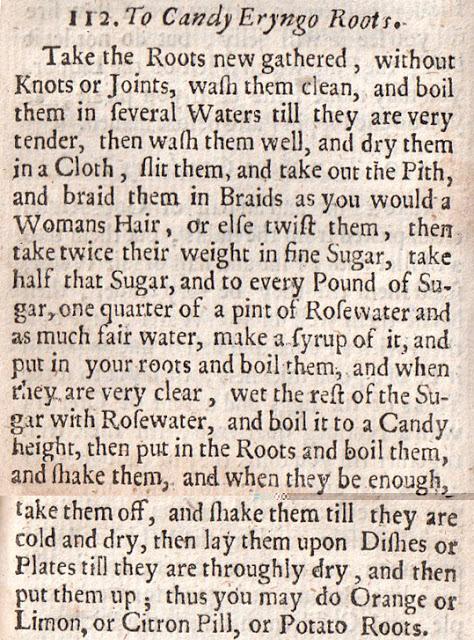

Hannah Wooley's 1670 recipe for candying eryngo roots suggests twisting or braiding the roots . This makes me wonder if this is the reason that Great's eryngo shop in Colchester was called The Twisted Posts and Pots

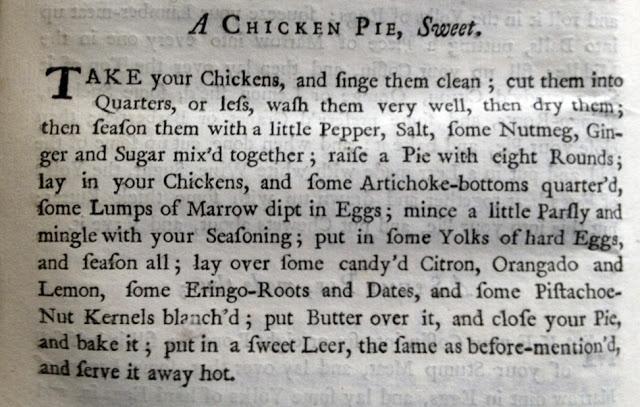

Although the candied roots were taken 'to provoke lust - even it would seem by bishops - they were also sometimes used as an ingredient in a number of pies and cakes. In his personal manuscript cookery book John Evelyn includes them in a recipe for a 'Hartichoak Pie', as well as in a moulded Eryngo Cream set with isinglass and garnished with pistachio nuts. The court cook Charles Carter puts them into a sweet Chicken Pie,

Charles Carter, The Complete Practical Cook. (London: 1730)

Like Evelyn, Carter also included eryngo roots in an artichoke pie. Plumcake pointed out to me a few years ago that these roots also feature in one of his cake recipes. In his diary he mentions a visit to Colchester and describes the town as being famous for oysters and eryngo candy. Perhaps he bought some while he was there. His Almond Cake contains a massive two pounds of them! Here is the recipe (courtesy of the late Christopher Driver).

To make an Almond Cake

Take 6 pounds of the finest flower drie it in the Oven after bread is drawne next morning rub it through a cource sive blanch 2 pounds of Almonds in cold water beat them with Orenge flower water very fine rub the Almonds into the flower very well then take 3 pounds of the best greene citron cut pretty small and 2 pounds of Eringo root cut small strew these into the flower one Ounce of Nutmegs and mace 3 parts mace a little cinamon a litle ginger wash pick and drie 5 pound of Corance lay them on a sive set them before the fire to keepe warme then beat 20 eggs all the whites beat them with a whisk very light straine them take two qts of the thickest creame put it on the fire slice in 4 pounds of the best butter let it stand till bloud warme a pint and halfe of new ale yest put a glass of sack to it and the eggs 4 ounces of loaf sugar beat fine strewd in then poure in the creame and butter on one side the yest and eggs in the other so melt yr cake very thinn and set it by the fire and at the first rising put in corance and let the Oven be ready at the second risng to put it into the Oven butter the hoop very well it will require somewhat better then two hours baking Ice it if you please.

I thought that Evelyn's cake with eryngo roots was a rare one-off example. But no! Plumcake also found another one in the manuscript receipt book of Margaretta Acworth.

A Sweete Meate Cake

Take eight pound of fflower and Rubb into it 3 pound of new butter. Put in 3 grated nutmegs and 3 pound of Carroway Comfitts. Put 1/2 the Comfitts into the fflower after the butter is rubbed in, then take 1 pint of Creame and a pint and a 1/2 of Ale yeast, 12 eggs keeping out 4 of ye Whites. Beate them very well then mix ye eggs and Creame very well togehter. Straine them, then add 1/2 a pint of sack, a quarter of an ounce of Carraway seeds, mix them all these with the fflower then set it before ye ffire untill your Oven is hott. Cover it warme and stir it often. Then take 1/2 a pound of Cittorne and 1/2 a pound of Lemon and Orange, 1/2 a pound of Ringoo Rootes. Slice all these and put them with ye rest of your Comfitts, then put your Cake into the hoope but be sure your oven be ready before you mingle it up. Put it into ye oven as soon as it is in ye Hoope. 2 Hours bakes it. When it is Drawne ice it.

I wonder if eryngo roots were included in these pies and cakes for their supposed venereal qualities, or just as a another sweetmeat? Their flavour, unlike candied peel is very subtle and would have been lost, especially in Margaretta Acworth's cake with its inordinate amount of caraway comfits and caraway seeds. Did a knowing manservant give his master a slice of one of these cakes with a nod and a wink? However, there is no scientific evidence that orchid tubers or eryngo roots contain any substances that have the ability to arouse sexual desire or improve sexual performance. One orchid variety described by Dioscorides in the 1st century AD with alleged aphrodisiac powers was called cynosorchis in Greek - meaning dogs testicles. This led to English folk names like 'dog's stones', 'dog's cullions' etc. The herbals of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries ascribe powerful venereal properties to all these plants. But the lack of any scientific evidence for these ancient claims makes me wonder if the whole story is just a load of 'dog's bollocks'.

Banquetting Stuffe. The white roots on the left are candied eryngoes.

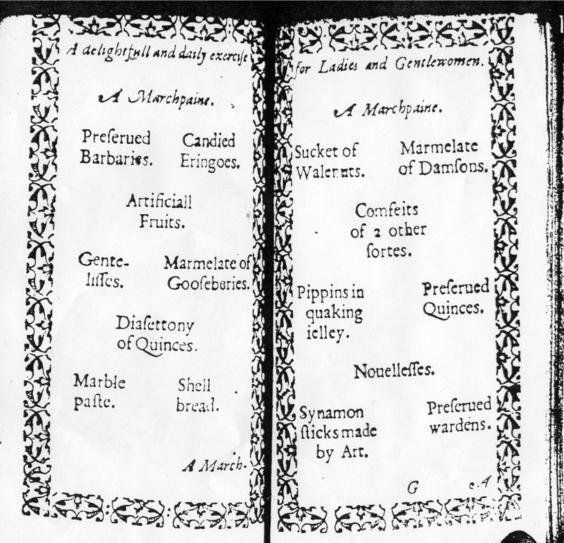

The banquet course of sweetmeats after the main meal, or as a sweet collation in its own right was the time when eryngo candy was usually served in early modern period England. These two suggestions for laying out a banquet course are from the very rare A Delightful Daily Exercise for Ladies and Gentlewomen by John Murell, published in London in 1621. This work is entirely different to the same author's A Daily Exercise for Ladies and Gentlewomen published in 1617.

Secondhand copies of Margaretta Acworth's Georgian Cookery Book edited by Alice Prochaska are also easy to come by. Pavilion - Michael Joseph 1988 ISBN 1851451242 (ISBN13: 9781851451241)

*Read much more about Eryngo in Ivan Day, Down at the Old Twisted Posts and Pots. PPC 52, 26.

An amusing video of the extraordinary sleight of hand of a Maraş ice cream maker and vendor in Istanbul