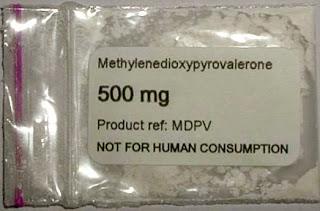

Popular bath salt drug shown to be highly addictive.

Popular bath salt drug shown to be highly addictive. Researchers at the Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) in La Jolla, California, appear to have hammered the last nail into the coffin for the common “bath salt” drug known as MDPV. We can now say with a high degree of certainty that, based on animal models, we know that 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone is addictive—perhaps more strongly addictive than methamphetamine, although such comparisons are always perilous. However, principal investigator Michael A. Taffe, an associate professor at TSRI, said in a prepared release that the research group “observed that rats will press a lever more often to get a single infusion of MPDV than they will for meth, across a fairly wide dose range.”

Like methamphetamine, MDPV works by stalling the uptake of dopamine, it also has effects on noradrenaline and serotonin. As cathinone derivatives, MPDV and mephedrone are related to the stimulant drug khat, which is used like cocaine in northeastern Africa. In earlier research at Scripps under Dr. Taffe, investigators found that lab rats would intravenously self-administer mephedrone and behave in a manner similar to the effects produced when the rats were on methamphetamine. In a paper for Drug and Alcohol Dependence, the Taffe Lab concluded that “the potential for compulsive use of mephedrone in humans is likely quite high, particularly in comparison with MDMA.”

Now the researchers have zeroed in on the effects of the dirty pharmacology represented by MDPV, the other primary ingredient in many bath salt mixtures. In a new study by Michael Taffe, Tobin J. Dickerson, Shawn M. Aarde, and others, to be published in the August issue of Neuropharmacology, the investigators found that MDPV was a more potent attraction than meth for rats allowed to self-administer the drugs. Very little lab data exists for MDPV, and this study was among the first to directly compare the effect of MDPV to methamphetamine in an animal experiment.

It took some time to tease out the behavioral clues—the cognitive, thermoregulatory, and potentially addictive effects of the drug—but MDPV’s strong affinities with speed can no longer be ignored. The researchers saw the same types of repetitive activities seen in animals on meth, such as excessive grooming, tooth grinding, and skin picking. Lead author Shawn Aarde said in a prepared statement that “one stereotyped behavior that we often observed was a rat repeatedly licking the clear plastic walls of its operant chamber—a behavior that was sometimes uninterruptable.”

MDPV, in the jargon of such experiments, had “greater reward value” than methamphetamine. Which is saying something, given the well-publicized addictive threat of speed. When the group boosted the number of lever presses needed for another infusion of MDPV or METH, “we observed that rats emitted about 60 presses on average for a dose of meth but up to about 600 for MDPV—some rats would even emit 3,000 lever presses for a single hit of MDPV,” said Aarde in a press release. “If you consider these lever presses a measure of how much a rat will work to get a drug infusion, then these rats worked more than 10 times harder to get MDPV.”

Excuse me, did he say as many as three thousand bar presses for another bump of intravenous MDPV? He did. Overall, the rats self-administered more MDPV than methamphetamine. In the paper itself, the authors write that “compared with METH, the effect of MDPV on drug-reinforced behavior was of greater potency (more responding under lowest dose under fixed-ratio schedule) and greater efficacy (more responding under optimal dose under a progressive ratio schedule)…”

The conclusion? MDPV’s “abuse liability” may be greater than that of standard methamphetamine. Which is another excellent piece of evidence for approaching the world of new synthetic psychoactives with great caution.