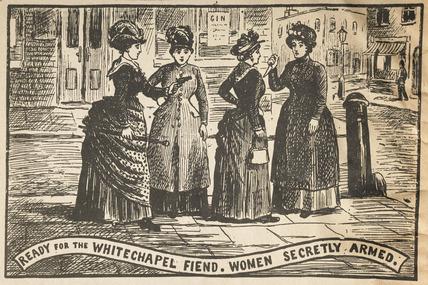

For those of you who missed it, here is the original draft (I made some amendments on the day) of the talk I gave at the 2013 Jack the Ripper Conference about Mary Jane Kelly, the last accepted victim of the Whitechapel Murderer.

I’ve entitled this talk, Mary Jane Kelly – International Woman of Mystery because that is how she has always appeared to be to me. I suppose that as a historical fiction writer, I am drawn towards Mary Jane precisely because of the air of mystery, much of which I think was cultivated by herself, that surrounds her. In a way she is a gift to a writer like myself – the most well known and discussed victim of perhaps the most famous serial killer of all time and yet we still know very little about her, which of course means that over time all manner of myths and fanciful representations of her have arisen – from the almost virginal whore of the film version of From Hell to the terrified confidante of a secret royal bride in Murder by Decree to the cocky Irish tart of the Michael Caine Jack the Ripper. Who is to say that any of it is wrong though and therein lies, I think, the crux of her appeal to those of us who like to weave works of fiction.

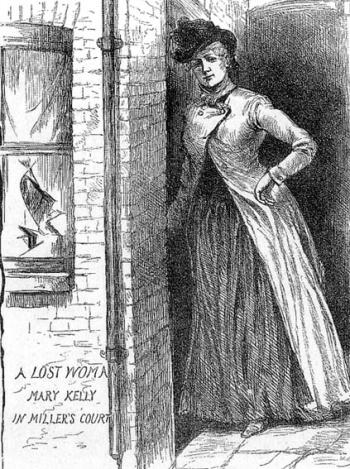

Of course, when you think about it, the only things that we know with any certainty about the woman who was found dead on the bed at number thirteen Miller’s Court is the date and manner of her death. We don’t even know if she was indeed Mary Jane Kelly, whoever she was, the murderer, having clearly anticipated our love of a jolly good mystery, thinking he’d help us all out a bit by removing her facial features and giving us something to mull over for the next hundred years or so.

It’s not massively helpful either, of course, that we don’t even know if Mary Jane Kelly was indeed the actual real name of the woman who was known to be resident at Miller’s Court throughout much of 1888. Certainly, her ex boyfriend, Joseph Barnett was under the impression that this was her name and we have him to thank for a lot of the information that now passes for fact about her background, personality and history. Personally though, I’d tread carefully when it comes to Barnett’s evidence – partially because I think there’s a very real chance that she was spinning him a few lines but also because, well, let’s face it, how many of us would want our entire life history for posterity dependant on what our exes choose to say about us? Not I, that’s for sure.

What we have to remember is that it was not entirely unknown for women in Kelly’s parlous situation in the late Victorian period to make use of multiple pseudonyms, living on the wrong side of the law as so many did or simply on the run from difficult personal situations like abusive fathers, violent husbands, debt, crime or prostitution. Certainly, she was not the only one of the Ripper’s victims that autumn to use an alternative name and we Ripper researchers come across many an interesting and evocative monicker during our work – from the fabulously named Pearly Poll, who was friends with Martha Tabram, to the rather more sinister Dark Annie, which always sounds ominously like ‘Dark Alley’ to me. We know that at some point, the woman who lived in Miller’s Court was known variously and rather colourfully and flatteringly as Fair Emma, Ginger or Lizzie Fisher at various points, but clearly she had decided on something more humdrum for her day to day life, settling on Mary Jane Kelly. Kelly, being a relatively common surname that three other Whitechapel murder victims (Eddowes, Tabram and MacKenzie) had also used at various points – probably picked because of the high amount of Irish immigrants on the streets of the east end at the time, with records from the period confirming that the surname Kelly appeared frequently in the 1891 census and admissions records for the local workhouses and infirmaries.

Back to Joseph Barnett. Mary Jane’s ex boyfriend clearly carried something of a massive torch for her and as a result had no doubt allowed himself to be beguiled by whatever she chose to tell him. It is to him that we owe most of the scant information about Mary Jane that we now have to work with, her actual family proving impossible to trace despite the best efforts of the authorities, police and press. Naturally, Barnett was in shock after being called to Miller’s Court to identify the horribly mutilated body of a woman that he had last seen alive and well the previous evening and whom it is likely that he was optimistically hoping to be reconciled with one day but nonetheless he seems to have put together a fairly articulate account of her life over the course of the following weeks when he gave a statement to the police, spoke at the inquest here in Shoreditch Town Hall and also granted some interviews to the press, perhaps in the hope that the information he gave about her would somehow come to the ears of her family. So what did Barnett have to say?

‘The deceased told me one occasion that her father named John Kelly was a foreman at some iron works and lived in Carmarthen or Carnarvon, that she had a brother named Henry serving in 2nd battalion Scots Guards, and known amongst his comrades as Johnto, and I believe the regiment is now in Ireland. She also told me that she had obtained her livelihood as a prostitute for some considerable time before I took her from the streets, and that she left her home about 4 years ago, and that she was married to a collier, who was killed through some explosion, I think she said her husband’s name was Davis or Davies.’

He obviously said a lot more than this but the crux is that, according to him, Mary Jane was in her mid twenties at the time of death, had been born in Limerick, Ireland before moving as a child, one of nine children (with a sister who worked as some sort of traveling saleswoman and seven brothers), to Wales then marrying a miner at the age of sixteen, becoming a young widow a couple of years later when her husband died in a tragic pit disaster. After this it all went downhill for her when she descended into prostitution in Cardiff after going to stay with a cousin there before moving on to London in the mid 1880s where she plied her trade in an upmarket brothel in the west end before a spell in France, after which she returned to the less salubrious parts of London – a slightly perplexing fall for a young woman of her alleged youth and good looks, who could presumably have done a bit better for herself than the mean streets of the Victorian east end.

This then was Joe Barnett’s tale – part Catherine Cookson, part Thomas Hardy, part Bret Easton Ellis. A tale of rural poverty, young love, tragic widowhood and a dismal fall from grace, leavened by the odd bits of tawdry glamour gleaned from that infamous and possibly fictional sojourn in France, which had nonetheless made such an impression on her that she Frenchified her name to Marie Jeanette. It makes for a good story – if lurid penny dreadfuls about fallen country girls are your thing, which I suspect may have been the case with poor old Joe Barnett, who, incidentally definitely cast himself as the hero of the piece with his reference to ‘taking her from the streets’ and in other words ‘rescuing’ her from her former immoral life. Like a sort of low rent Pretty Woman.

But how much of it is true? Well, here’s the rub. Whereas, the other victims of the so called Whitechapel Murderer, despite the relative humbleness of their lives, left quite definite paper trails behind them in the form of census records, marriage records, birth certificates, entries in infirmary and workhouse registers and so on, we have nothing like that for Mary Jane, even though she seems to have quite explicitly mentioned a marriage and subsequent widowhood and was obviously born herself at some point. In short, not one single thing from Barnett’s account of his ex lover’s life before she came to London can be absolutely verified from the available records of the period.

For example, if we take the alleged marriage, this should be the easiest thing of all to trace given the relatively small time frame, the area and the information offered by Barnett, namely:

Her name – Mary Jane or Marie Jeanette Kelly.

The surname of her alleged husband, which was either Davies or Davis.

If she was 25 at the time of her death then her marriage took place in around 1879 when she was 16.

The marriage took place in Wales, either in Carmarthen, Carnarvon or Carnarvonshire.

However, despite the best efforts of several researchers, and who hasn’t had a go at tracing the elusive Mary Jane Kelly in the records by now, not a single one has managed to find a single marital union that even partially fits the bill – even allowing for a wide range of variants in the names of the happy couple and the year in which they were married.

Even approached chronologically and allowing for the vagueness and inconsistencies of Barnett’s account of Mary Jane’s life, there is nothing that can be absolutely verified.

1862/3 – Mary Kelly is born in Limerick.

? – Mary Kelly moves at a ‘very young’ age to Wales.

1878/9 – Mary Kelly marries the collier Davis or Davies.

1880/2 – Davies or Davis dies in a pit accident.

1880/2 – 1884 – Mary Kelly moves to London.

1887 – Mary Kelly and Joe Barnett meet.

1888 – Mary Kelly is murdered.

There should be plenty here to be going on with surely or so you would think, especially when you add all the extraneous details about periods in an infirmary, her time in a West End brothel and that short lived trip to France, which seems to have come to an abrupt end when she decided that she don’t like it and did a runner back to London.

It should be pointed out that a City missionary would also claim acquaintance with Mary Jane in a piece in the Evening News shortly after her murder and would confirm Joseph Barnett’s evidence that she hailed from Limerick in Ireland.

‘I knew the poor girl who has just been killed, and to look at, at all events, she was one of the smartest, nicest looking women in the neighbourhood… I know that she has been in correspondence with her mother, it is not true, as it has been stated, that she is a Welshwoman. She is of Irish parentage, and her mother, I believe, lives in Limerick. I used to hear a good deal about the letters from her mother there. You would not have supposed if you had met her in the street that she belonged to the miserable class she did, as she was always neatly and decently dressed and looked quite nice and respectable.’

This tale about Limerick was also confirmed by her friend Elizabeth Foster and also her landlord, John McCarthy, who stated that:

‘Her mother lives in Ireland, but in what county I do not know. Deceased used to receive letters from her occasionally.’

It would seem therefore that it is with the accounts of Mary Jane’s family that we should by rights be able to solve the mystery of her identity, especially when it comes to the few facts that more than one person would seem to agree upon, such as her family originally coming from Limerick and the continued existence of her mother, but it seems that for now we must draw a blank. Obviously a family with nine children was unusual but not all THAT noteworthy in the Victorian period (after all Queen Victoria herself had nine children) – when contraceptives were dodgy and television non existent, however it does tend to narrow down searches on census reports because then as now, families with that many children were still somewhat in the minority.

However, here again we can find nothing definite. There is one family in the 1871 census that could accord with what we know about the victim at Miller’s Court, if you assume that she was genuinely called Mary Kelly, was born in Ireland and then moved to Wales as a child –

Address 84 Mumforth Street, Flint, Wales.

Head: John Kelly, aged 36, born Wicklow, Ireland – labourer

Wife: Ellen Kelly, aged 30, born Dublin, Ireland.

Children:

Elizabeth, aged 10, born Wicklow, Ireland.

Mary Ann, aged 7, born Wicklow, Ireland

Patrick, aged 4, born Portelley, Carnarvonshire

John, aged 11 months, born Flint

If this Mary Ann Kelly was seven in 1871 then she was born 1863/4 which would fit in with the Joe Barnett version of his ex girlfriend’s life story. There are also those connections to Ireland, Carnarvonshire and Wales as well as the one sister and what seems to be the beginnings of a series of brothers. However, in the 1881 census, the family hasn’t increased and, more significantly Mary Ann, by then sixteen, is still resident with her family.

Of perhaps more interest is the seventeen year old Mary Kelly listed in the 1881 census as living in Brymbo (Brim-bo), Denbighshire with her family.

Address: Broughton (Brow-ton) Colliery Cottages, Brymbo (brim-bo), Denbighshire.

Head: Hubert Kelly, aged 51, born Ireland, general labourer.

Wife: Bridget Kelly, aged 47, born Ireland.

Children:

Michael, 25, Ireland, labourer.

John, 24, Ireland, labourer.

Hubert, 19, Ireland, labourer.

Mary, 17, Ireland, servant.

Patrick, 13, Ireland.

Elizabeth, 10, Ireland.

Garret, 7, Denbigh Lodge.

Thomas E, 4, Ireland.

Timothy, 1, Denbigh Lodge.

Of course the most interesting thing about this Mary Kelly is that not only was she born in Ireland before moving to Wales at perhaps around the age of ten if we can assume that Garret was born shortly after the family’s arrival in Denbighshire or perhaps seven if they moved when Elizabeth was a baby but that, as Joe Barnett claimed, she has one sister and seven brothers.

When we look again at this family in the 1891 census, great changes have occurred in the Kelly family of Denbighshire:

Address: 12 Poplar Road, Wrexham Regis, Denbighshire.

Head: Bridget Kelly, aged 58, born Ireland, widow.

Children:

Patrick, 23, born Ireland, colliery banksman.

Elizabeth, 20, born Ireland, dressmaker.

Garret F, 17, born Denbigh, colliery banksman.

Thomas Edward, 13, born Ireland.

Timothy, 11, born Wrexham, Denbigh.

So in the intervening ten years, the father has died and the four eldest children, including Mary, have all scarpered to presumably their own lives. And this demonstrates the problems with the official records – either the name fits and the family doesn’t or vice versa and at this time it is impossible to work out which is which. There is also a particular difficulty when tracing the lives of women too as they commonly change their surnames upon marriage, at which point, if you’re dealing with incomplete records, creative spelling and commonplace surnames, this can become a real problem. And so at this point, the Mary Kelly of Denbighshire falls from view – either married, working as a domestic in another household or dead.

Of course, more intrepid researchers have also concentrated their efforts on the bit part players in our mystery woman’s story – such as her alleged brother, Johnto, who was apparently in the 2nd Battalion Scots Guards and of whom no trace can be found. I’d disagree with some researchers though who claim that it is unlikely that a Welsh boy would join the Scots Guards as my own grandfather’s family hail from Flint in Wales and there is a family tradition, followed by he himself of joining the Scots Guards not the Welsh or Irish. (As an aside for anyone who is thinking things here – I’ve checked back as thoroughly as I can and I’m almost definitely NOT Mary Jane Kelly’s long lost relation.) However, the lack of evidence for anyone who might conceivably be her brother in the Scots Guards at that time would suggest that he too was a fabrication or perhaps a crude attempt to use a former lover to embellish her tale – possibly because she was worried about being seen out and about with a man in uniform and this getting back to the smitten Joseph Barnett. It’s easier by far to explain it away as a quick meeting with a ‘brother’ about to be sent overseas than yet another ex boyfriend.

However, recent research HAS managed to verify one of the more confusing facts in Joe Barnett’s tale of misery and woe –

‘…She was living near Stepney Gas Works. Morganstone was the man she lived with there. She did not tell me how long she lived there. She told me that in Pennington Street she lived at one time with a Morganstone, and with Joseph Flemming, she was very fond of him. He was a mason’s plasterer. He lived in Bethnal Green Road…’

Mary Jane Kelly’s mysterious ex boyfriend Morganstone was identified by Neal Shelden and also Evans and Connell in 2000 as a Dutch gas stoker by the name of Adrianus Morgenstern. Armed with this fact, the rather splendid Jen Shelden managed to track Adrianus down in the 1891 census as having changed his surname to Felix and be living in Limehouse with one Elizabeth Felix, who was presumably the same Elizabeth Phoenix who was chums with Mary Jane and who had claimed to the police after the murder that Mary Jane was living with her brother in law in Breezer’s Hill.

‘She stated that about three years ago a woman, apparently the deceased from the description given of her, resided at her brother-in-law’s house, at Breezer’s Hill, Pennington Street, near the London Docks. She describes that lodger as a woman about 5ft 7in in height, and of rather stout build, with blue eyes, and a very fine head of hair, which reached nearly to her waist. At that time she gave her name as Mary Jane Kelly, and stated that she was about twenty two years of age, so that her age at the present time would be about twenty five years. There was, it seems some difficulty in establishing her nationality. She stated first that she was Welsh, and that her parents, who had discarded her, still resided in Cardiff, whence she came to London. On other occasions, however, she declared that she was Irish. She is described as being very quarrelsome and abusive when intoxicated, but ‘one of the most decent and nicest girls’ when sober… When living at Breezer’s Hill, she stated to Mrs Phoenix that she had a child aged two years, but Mrs. Phoenix never saw it.’

Clearly this brother in law was Johannes Morgenstern, Adrianus’ brother, who in 1885-6 was living at 79 Pennington Street on the corner of Breezer’s Hill – with a widow called Elizabeth Boeku (Boo-ky), who must surely be the mysteriously monickered Mrs Bucki, with whom Mary Jane apparently lodged on St George’s Street in the parish of St George’s in the East and who, according to Barnett went with her to the west end brothel that she had once been a resident of to demand her old dresses and belongings back.

Another ex lover from this period was Joseph Fleming, who most probably replaced Morgenstern in her affections and who can also be traced with some confidence in the records. He was apparently born in Bethnal Green in the second quarter of 1859 and according to the 1881 census was living in lodgings in 61 Crozier Terrace, Homerton, which is close to Bethnal Green although recent research would suggest that he was a resident at the Bethnal Green Workhouse for at least some of 1888 so he may have fallen on hard times by that time. He was working as a plasterer in 1881 though, which completely fits with Joe Barnett’s account of events and which would suggest quite strongly that although Mary Jane was perhaps fond of embellishing her past background, she was at least relatively honest about her more recent life, probably because there were plenty of people around who could grass her up if she tried to lie about what she’d been up to, and in turn this would suggest that any theories that she was living in a place other than the east end of London immediately before meeting Joe Barnett in 1887 are most likely false as she was clearly resident in London for quite some time before they met.

Ultimately, we know virtually nothing about the actual identity of the young woman who was found dead on this chilly morning 125 years ago and yet, ironically, she is the victim who continues to exert the most fascination and who makes the most appearances in fictional accounts of the murders – perhaps because of the aforementioned blank slate afforded by this faceless corpse with no apparent traceable background but also because she herself has come down to us, rightly or wrongly and probably very wrongly, as something of a romantic figure – the youngest of the Ripper’s victims (allegedly although if we can’t even trust her name, why should we pay any attention to her alleged age – after all it’s not ENTIRELY unheard of for women of her type to be somewhat coy if not downright fibbing about their ages) and quite likely the most physically comely. I suppose it makes sense therefore that she exerts a perhaps more powerful draw than the other victims as a look at the discussion threads on casebook.org and JTRforums.com demonstrates:

JTR Forums:

Mary Ann Nichols – 32

Annie Chapman – 29

Elizabeth Stride – 55

Catherine Eddowes – 55

Mary Jane Kelly – 196

Casebook:

Mary Ann Nichols – 49

Annie Chapman – 65

Elizabeth Stride – 119

Catherine Eddowes – 97

Mary Jane Kelly – 341 +++

Of course, many of these threads involve speculation about Mary Jane’s identity and discussion of the Barnett story of Catherine Cookson rural woe – which adds an element of mystery that is perhaps missing from the other victims, whose lives are relatively so well documented. And this too explains the prominence with which Mary Jane features in most of the best known fictional accounts and theories. I think we’re all familiar with the Royal Conspiracy Theory (I think I’ll pause here to let you all have a good old groan about it), which at its heart stars that most favorite suspect of Daily Mail readers everywhere, Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and second in line to the throne, who according to the hoary old tale knocked up a shop girl by the name of Annie Crook and may even have married her – a story that formed the basis for the well known book and film From Hell as well as Murder by Decree and which allows a starring role for Mary Jane Kelly, the confidante of the hapless Annie, witness at her wedding and, in some versions, nursemaid to the royal by blow, Alice. Annie’s other friends are killed with increasing savagery but it falls to Mary Jane’s lot, as the main instigator and most involved in the illicit affair and subsequent crude blackmail attempt to be killed last and with particular brutality – to teach her some sort of lesson for not knowing her place, one supposes.

In another account of the murders – Leonard Matters’ The Mystery of Jack the Ripper, which was published in 1929, we are led into the dark and gruesome world of the unhappy Dr Stanley whose beloved son dies from a particularly heinous venereal disease, at which point the distraught Doctor heads off to the East End to track down the woman who is responsible for his son’s untimely demise – that woman, of course, being Mary Jane Kelly. This book, of course, inspired the 1959 Jack the Ripper film, which had as its arc, the murderer prowling the foggy streets and asking improbably attractive ladies in big hats and feathered hats if they know ‘Mary Clark’ before presumably getting bored with their denials and offing them instead. +++

In Silence of the Lambs, during Dr Hannibal Lecter’s last fraught face to face chat with Clarice Starling he tries to help her identify the murderer known as Buffalo Bill by asking her ‘Of each particular thing ask: what is it in itself? What is its nature? What does he do, this man you seek?’ before reminding her that ‘We begin by coveting what we see every day’ and that therefore she needs to go back to the very beginning, to the first victim to find her man. I always remember this when I’m working on my Ripper research and particularly in relation to the particular interest in his LAST victim – a murder that is often interpreted as the most defining of the series of killings, not just because of its particular savagery but also because of the character, as far as we know, of the victim. It certainly seems to me that Dr Lecter would be amused and frustrated by this emphasis on the last victim, the grande finale of the gruesome events of autumn 1888, rather than a more logical look at what went before and why it was that poor Martha Tabram or Polly Nichols, depending on where you stand on how it all began, caught the eye of our murderer. Perhaps it was chance that threw them in his path but it wasn’t chance that made him take his knife out with him.

And I think that it is this particular savagery, this bestial brutality that has much to do with it – we’re all appalled of course by what happened to Mary Jane Kelly (seen here with a rather fetching shade of red lipstick in the Madame Tussaud’s Chamber of Horrors during the eighties) during the early hours of the ninth of November 1888 but isn’t there a germ of ‘why did that happen to her?’ and maybe even ‘what did she do to deserve that?’ (in his mind at least) that perhaps elevates her above the other victims, canonical and otherwise, and makes us see her as the CENTRAL target of the series of murders, the ultimate goal as it were and the very heart of the problem. And it is this that also leads some of us to wonder if perhaps she had more of an influence on the ultimate motivation of the killer, whose own back story is, of course, as much of a mystery as that of Mary Jane Kelly. Perhaps this too explains the fascination with unravelling the identity of the woman who died so horribly in 13 Miller’s Court – this sense that if we identify her then perhaps that will directly lead us to the man who killed her. I personally doubt it but it’s an enticing idea and one that keeps the mythology that surrounds both victim and killer alive and kicking even though both are long dead – this being one of the very few certainties about the case in fact.

And also let’s not forget that, dreadful though this undoubtedly is, Mary Jane Kelly is generally regarded to have been not just the youngest but also the most attractive of the victims. Now of course this really shouldn’t matter at all but we all know from our own experience of today’s media that if two people go missing around the same time it is the more stereotypically photogenic of the two that will garner the most attention and sympathy. For some reason, it just really bothers people a lot more when a bad thing is perceived to have happened to a good looking person and I definitely think that there is more than an element of that going on here. Not that people are looking at the mortuary photo of Annie Chapman and thinking ‘eh, fair enough, who cares?’ but certainly the fact that there is a lot more interest in Mary Jane Kelly than in poor old Annie would suggest a certain difference in the way that the two women are being viewed and, yes, judged by an often harsh posterity.

However, is this really fair? I mean, obviously Mary Jane Kelly was IN NO WAY as attractive as Heather Graham even when she wears the same frock for the course of one film and gets a little bit grimy in alleyways. In fact, words that were most commonly used to describe the real Mary Jane Kelly by people who claimed to actually know her were ‘pretty’, ‘attractive’ and ‘stout’, which even allowing for the changing standards over the centuries is not a word that has generally been considered to have the most beauteous connotations. Elizabeth Felix also mentioned that although Mary Jane had beautiful hair, she also had two false teeth in her upper jaw that stuck out quite prominently, which, I don’t know about you, but I think even the likes of Kate Moss would struggle to rock that particular look. Then again, the women of Whitechapel and not just the Ripper’s victims, had tough lives by any standards so who knows, maybe she WAS a raving beauty in comparison to your average street walker hanging about the bar of the Ten Bells but she wouldn’t, say, pass muster at a court ball, on the stage of a West End theater or a gathering of artist models in Bohemian Chelsea. It’s all relative. +++

All of which is a very long winded way of saying that we are still no closer now to identifying Mary Jane Kelly or whoever she may have been even after all these years. However, that’s not to say that we should just completely give up hope. The fact is that she DID exist and like all of us, whether we’re happy about this or not, she had parents, family, friends, a birthdate and a place that she called home, whether that was Whitechapel or somewhere else altogether more salubrious. Therefore there is, I believe, a fairly strong chance that somewhere out there the key to solving the whole Mary Jane Kelly mystery is lying unknown and forgotten in some dusty attic, photo album or family bible – just waiting for someone to recognize it for what it actually is. Okay, it’s probably more realistic to assume that we know as much now as we ever will but who can say? Thanks to the amazing work of several really devoted researchers including Chris Scott and the Sheldens (all of whom I am especially indebted to for their input in this talk) we already know more now about the lives of all the Ripper’s victims, both canonical and otherwise than we did at the time of the centenary in 1988 and even fifteen, ten, five years ago.

(Many thanks again to Neal and Jennifer Shelden and Chris Scott for their input into this talk.)

******

Check out my new alternative lifestyle blog, Gin Blossoms!

‘Frothy, light hearted, gorgeous. The perfect summer read.’ Minette, my young adult novel of 17th century posh doom and intrigue is now £2.02 from Amazon UK and $2.99 from Amazon US.

Blood Sisters, my novel of posh doom and iniquity during the French Revolution is just a fiver (offer is UK only sorry!) right now! Just use the clicky box on my blog sidebar to order your copy!

Follow me on Instagram.