Our grandparents and parents are fighting, and we don't like it. That's my general takeaway from watching Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola fight the likes of James Gunn and Jon Favreau over the state of cinema in the age of Marvel. Can populist entertainment still be cinema? Is even using the word "cinema" the most pretentious thing possible? Are movies doomed - doomed, I tell you?

The answers: Yes, kinda depends on where you live, and no, but it's still not great.

However, isn't this basically the same fight we've been having for years? Wasn't it just a couple of years ago that the Academy gave Best Picture to a film, Birdman, which was a giant fuck you to comic book movies? ("You took-up space in a theater which *otherwise* might have been used on something worthwhile," seethes one art critic to Michael Keaton's character.) Wasn't Peter Biskind crying about Hollywood "infantilizing the audience" back in 1999? Didn't William Friedkin rage against Star Wars and compare it to "like when McDonald's got a foothold, the taste for good food just disappeared"?

Whenever art goes low, the critics go high.

Complain as the Romans Did

I sometimes wonder if in the moments after man first discovered fire, buried in the crowd of transfixed cromagnums there was one dissenting voice arguing, "Me miss time before fire. Life purer then."

(That's how caveman talked, right?)

Point being: whenever anything changes, there is bound to be pushback. This is not my attempt to equate the invention of fire with the grandiosity of the Marvel Cinematic Universe in the pantheon of human achievement. (Although Thanos is one of our greatest achievements, right?) However, it does seem like humanity has a historical proclivity for viewing any advancements as an assault on the past.

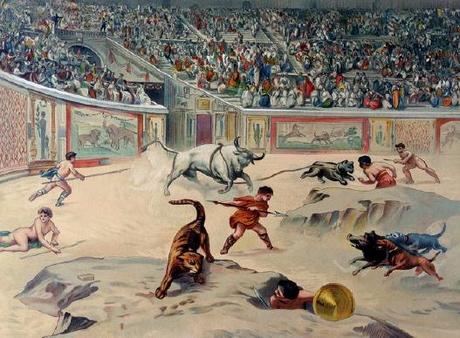

The better historical antecedent, in this case, would be the creation of the Roman circuses. That's kind of history student 101 for "example of thing used to distract the masses," but as historian Jerome Carcopino argued, "The caesars exhausted their ingenuity to provide the public with more festivals than any people, in any country, at any time, has ever seen."

Them's fightin' words. "Such sights are for the young," Pliny the Elder said. "These and similar things prevent anything memorable or serious being done in Rome," agreed Cicero.

Cicero was later executed for speaking out against Marc Anthony. Hmm. That's not so fun, actually.

Cicero was later executed for speaking out against Marc Anthony. Hmm. That's not so fun, actually. By the 18th century, writers had a newer way of classifying it: fine art contemplated purely for aesthetics vs. craft art that is more utilitarian. Over time, this evolved into high art vs. low art, not always for the best. As The Rapidian explained:

"This affects how people interact with the arts. Those who place a greater value on high art sometimes believe that high art serves a kind of spiritual or moral function. A common assumption is that high art is "edifying" and low art is "mere entertainment." If only the masses can be steered into the concert halls and museums, the power of high art will awaken them from their low art-induced stupor. To them, art has a quasi-religious function, with beauty lifting us to a higher level of spirituality. It's no accident that museums are often designed to feel like temples.

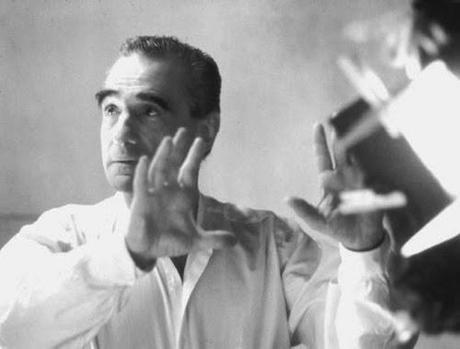

For Scorsese and Coppola, the movie theater is their temple, and they don't much care for the oafish boor who has moved in. It's not exactly as if Scorsese and Coppes - a nickname I just made up and will never use again - have always been exclusive purveyors of high art. Have you seen Shutter Island? Beyond that, drive-in movie critic Joe Bob Briggs often tells the story about the time he chatted with Scorsese on the set of Casino. Unprovoked, the diminutive, bushy eye-browed legend proceeded to school Briggs in the history of the women in prison genre.

The guy who made Goodfellas knew more about a B-movie exploitation genre than the guy whose job it is is to be an expert in that kind of thing. However, in the 70s Scorsese probably wouldn't have wanted the women in prison genre to be the only kind of film which got made, and he sure as heck wishes there was more going on at cineplexes right now than superhero dominance.

What Marty Said

He wasn't exactly a Star Wars fan either. "Star Wars was in. Spielberg was in. We were finished" is his quote from Easy Riders, Raging Bulls.

He wasn't exactly a Star Wars fan either. "Star Wars was in. Spielberg was in. We were finished" is his quote from Easy Riders, Raging Bulls. The great Marvel vs. Cinema debate of 2019 is a feud tailor-made for the age of Twitter. It's a game of telephone, really. A Martin Scorsese quote (""It isn't the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being") about Marvel movies from an Empire Magazine interview is parroted on the internet enough that those with a little skin in the game feel the need to defend their career choices or take the high ground and accept the criticism graciously. Unsatisfied, the media - ever desperate for virality and readymade conflict - push microphones in front of just about anyone they can find and asks, basically, "Scorsese said this disparaging thing about the only movies anyone actually pays to see in theaters anymore. Care to respond?"

Similar dynamics play out on Twitter on a regular basis. Right now, Tusli Gabbard and Hillary Clinton are feuding for, um, reasons. Prior to that, it was the NBA vs. the entire country of China. This is the stupid way the world works now. We're forever stuck in a reactionary loop, one outrage leading to the next. Anyone not perfectly trained in media management - and even some who are - are doomed to an existence in which just one poorly chosen word can lead to them being ratioed or canceled.

Some people - like Robert Downey, Jr. during a Howard Stern appearance - have been too smart to take the bait. Others like James Gunn just can't help themselves. Now, the story has grown. Scorsese doubled down. Francis Ford Coppola, Ken Loach, and Fernando Meirelles have each thrown their support behind Scorsese's grim view of things, with both Coppola and Loach going even further with it, alternately labeling Marvel movies as "despicable" and "commodities like hamburgers." (It should be noted Coppola offered his assessment completely unprovoked whereas Loach and Meireles were asked about it directly.)

Jon Favreau - the rich-beyond-his-wildest-dreams Iron Man filmmaker turned stone-cold businessman who has chosen to adapt to the times rather than lament that his earlier indie movies couldn't be made the same way today - said these legends of cinema have earned the right to criticize. Even that set Twitter afire. You shouldn't have to be one of the greatest directors of all time to have the right to be critical of what comic book movies are doing to the industry...and all that.

As this all played out, I chose not to engage. Everyone lost their mind because a septuagenarian (Scorsese is 76) and octagenarion (Coppola is 80) who made some of the best films of all time said they don't like comic book movies? Isn't that exactly what you'd expect them to say? When paradigms change in Hollywood, the old guard rarely rushes to endorse the new.

Plus, this is a bit been there, argued that. We already had this same argument in 2015 when Birdman's creators and Dan Gilroy badmouthed comic book movies. However, it's been percolating in my head for the past two weeks, and just the other day I found inspiration in the most unexpected place. A certain old movie just happened to pop up on Turner Classic Movies.

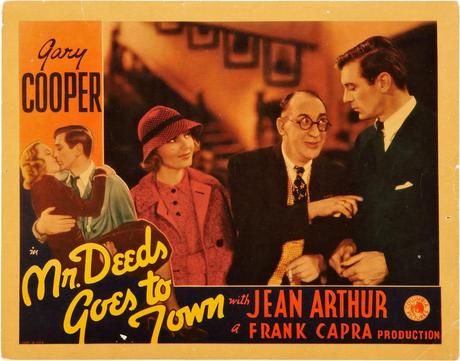

Let Me Tell You About a Man Named Deeds

In Frank Capra's Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, Gary Cooper plays a simple, small-town man who inherits a fortune and gets a firsthand view of what being rich is really like. It's the kind of plot we've seen many times throughout film history. There's simply a long-lasting appeal to showing the poor exactly how the other side lives. (Heck, that's Instagram's entire MO now.) In this particular case, something Mr. Longfellow Deeds - yes, his name is Longfellow, but we are talking about a 1936 film here - discovers is that as a member of the stupid rich he is now expected to support the arts. This does not sit well with him.

Going over the books and listening to a local opera board's appeal for a renewal of their annual funding of $180,000, he has a simple question: do they actually make any money? "Of course not, but since when has the mattered?" is their basic response. "We must give the wrong kind of shows," Deeds sheepishly replies. In a huff, the Italian Opera Board member bellows in the most pretentious "artiste" voice imaginable, "The wrong kind? Why, there isn't any wrong kind or right kind. Opera is opera." His voice actually goes up an octave on that last line, as he practically sticks his nose up at the ignorant, uncultured fool in front of him. Deeds walks out of the meeting.

Spoiler alert, by the end of the movie Deeds chooses to use his money to help farm families suffering from the Great Depression, and when those corrupt individuals who control the family's purse strings challenge his sanity in court he literally punches them in the face to grand applause and kisses from Jean Arthur.

One thing: Movies used to be so very different.

Another thing: Frank Capra movies aren't subtle.

Another another thing: Even in 1936, the world was aware of the question of art as commerce vs. art for art's sake. Mr. Deeds Goes to Town was, itself, a successful piece of populist entertainment. Opera, not so much. So, which one has more value? And how do you even define "value"?

Like Deeds and his opera hesitations, those looking to actually make a buck in Hollywood have always had better options than investing in the kind of art doomed to a limited appeal. If they opt to make more populist entertainment, is that a lesser art form? Is Halloween worse than Gandhi just because one is entertaining and one is not but seems "important"? However, is a world in which a younger generation is being raised on an exclusive diet of escapist entertainment in the mold of a Marvel movie truly the best thing? If each generation is inspired to make films like the ones they loved as a child, what will cinema look like in 20 years? Might future director Q&A's open with, "I was so inspired by what they did in Hobbs & Shaw "?

Isn't this somehow all Steven Spielberg's fault?

Let's Jump Ahead to 1992

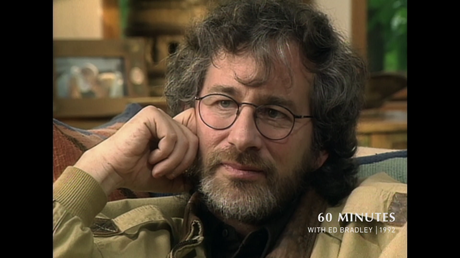

As seen in the HBO documentary Spielberg, 60 Minutes ' Ed Bradley once asked Steven Spielberg the following question, "Let me get you to react to something one of your peers said, a fellow director..."

Before Bradley even gets the rest of the sentence out in this 1992 segment, however, the camera cuts to a reaction shot of Spielberg looking like he knows exactly what's coming next and he just can't anymore with this shit. Bradley, quoting without specifying who exactly he's quoting, says, "'Steven Spielberg can't be compared with people like Mike Nichols and Barry Levinson. There is a place for mass entertainment but it shouldn't be confused with art or quality, award-winning filmmaking'."

This is Spielberg after he'd made The Color Purple and The Last Emperor and right before he was about to create his masterpiece, Schindler's List. However, to many, he and George Lucas were the ones to blame for destroying the Hollywood that had been and turning it into something they despised, a criticism which dogged Spielberg for his entire career to that point.

His response: "Sometimes I think statements like that are pretentious in themselves because it sort of says that, you know, art is serious and art can't be-can't move you, art can't be on a bicycle with E.T. and fly across the moon, that that can't be art."

You hear echoes of this in James Gunn's defense of Marvel movies today.

And Finally Today

We are still suck in this centuries-old loop - high art vs. low art, soul enrichment vs. mass entertainment. Today, it's taken on a new dimension: that which is culturally important and thus shouldn't be measured by first-weekend results vs. Twitter battles between which company or filmmaker can make the funniest GIF whenever a new movie breaks the box office record they used to hold. (Ryan Reynolds, predictably, is usually the best at it.)

The latest iteration of this argument doesn't want to go away. It's the question everyone has to answer now, as seen in this excerpt from THR 's "Today in Entertainment" newsletter:

The head of Disney and thus the de facto leader king of Hollywood feels compelled to stick up for his employees? Damn, this rocketed to the top of the industry food chain fast.

The Hottest of Hot Takes

This was a notable enough development that other outlets which had otherwise stayed relatively quiet felt compelled to offer their take:

"Scorsese and his ilk have better things to do, and so does anyone who delights in the broad range of possibilities that movies offer up. Marvel movies exist. It's time to move on."

"But Scorsese and Coppola are asking something elemental: Do we want a movie culture - an art culture - where everything is programmed and scannable, with no hidden levels, so that movies no longer reflect the mystery in ourselves? Some might say, "We do!" But I would say be careful what you wish for."

The ever-snarky Vulture struck a far more exasperated tone:

My Take

If you take the two dominant forces in entertainment over the past 25 years - blockbuster movies and serialized, bingable storytelling - and combine them together you get the Marvel Marvel Cinematic Universe. No wonder they've been so popular.

Yes, "cinema" is dying, that is if you define "cinema" in the somewhat pretentious terms as a dominant art form that seeks to illuminate truths about the human experience and would never stoop to simply entertain and certainly never try to do both. That is simply not the kind of movie which is going to top the box office anymore, but it's not like it's completely gone. Idiosyncratic cinema is all around us. See: Midsommar, The Lighthouse, Parasite.

Beyond that, cinema is morphing into fantastic TV, the best in the history of the medium and often times better versions of what would have been possible in a simpler two-hour movie format. Watch Adam McKay's overly condensed and simplified, failed Oscar contender Vice and then watch his critically adored HBO series Succession for proof of the current superiority of long-form storytelling.

Yes, Marvel movies and others like them can be assembly-line commodities, four-quadranted to the point of mindlessness and, worse yet, potentially peddling an overly simplistic fantasy view of the world. You know what else though? Some comic book movies are nuanced, deeply strange, and possessed of the idea that the best way to say something about the world is to trojan horse your message inside something people actually want to see. (Have you watched Watchmen yet? So much to say about that show's take on racism.)

Take the Hit

Still, I think back to something Marc Maron said earlier this year on Conan O'Brien's show. Even though he is actually in Joker, Maron admitted he doesn't really like comic book movies. He trotted out the usual explanation - they're juvenile entertainment meant for kids and adults who really should grow up. Not surprisingly, the studio audience turned on him and booed. Confrontational as always, Maron leaned into the moment, taunting the audience, "Oh, really. Take the hit. You guys are in charge of culture."

I disagree with his broad dismissal of comic book movies, but I agree with that final sentiment. Anyone who loves comic book movies and has a problem with what people like Maron, Scorsese, and Coppola says about them should just take the hit. We are currently in an unprecedented era where one single film genre has achieved an unbroken run of worldwide box office dominance and is now also everywhere on TV. It's only natural for some to cry for mercy and ask if this is really the best direction for our culture to take.

HBO's Watchmen, meanwhile, was the cable network's most-watched new shows in years. A mazon's The Boys is reportedly one of the streaming giant's most-watched originals. Three of the top five films of 2019 have superheroes in them. And you have to go to a special website to figure out if Martin Scorsese's The Irishman - a Netflix Original - will play in any theaters near you. (The closest theater is 132 miles away.)

Forget it, Marty. That's Marvelmovieland.

The roman circuses displeased the high-thinkers, and with the Marvel movies, Hollywood's old guard is getting cranky. By all historical precedent, this should have petered out by now. It's not, though, and if anyone is getting a bit tired of it we should just take the hit. Marvel isn't going anywhere.

What about you? Let me know in the comments.