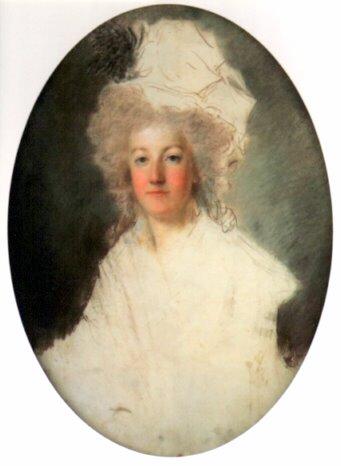

The woman appears much older than her thirty seven years, dressed in a shabby rusty black gown with a patina of faded mold around the hem and a crumpled fichu arranged around her shoulders, she looks exhausted and pale as she slumps on the rough wooden bench. Her prematurely gray hair falls in untidy ringlets from beneath her white linen cap and her red rimmed blue eyes peer through the candlelit gloom at the crowd of unsympathetic black clad men who stare back at her.

‘Do you have anything to add to this sentence, Citizeness?’

The woman pauses then frowns and shakes her head, her eyes fixed on the large medal that swings on a ribbon around his neck. ‘La loi’ its engraved writing proclaims. ‘The law.’

‘Then you are dismissed.’

They all continue to stare as the woman stands up, automatically shakes out her skirts as though they are made from the finest silks and brocades instead of plain cotton then begins to walk silently from the dark courtroom, limping slightly thanks to the painful rheumatism that has lately begun to affect her joints and makes them creak and grind agonisingly against each other.

‘She looked surprised,’ one of the judges whispers to another, the enormous black plumes tucked into his hat waving as he sniggers nastily. ‘Did she think, perhaps, that we would let her go?’

If she hears him, she gives no sign as with a weary effort she lifts her chin and leaves the chamber, walking passively in the middle of the crowd of silent, grim faced gendarmes who lead her back to her shabby cell on the ground floor of the prison, her high red heels clicking slightly on the terracotta tiled floor.

One of the gendarmes peers out of a thin window set into the thick stone wall and takes out his watch to check the time: it is 4.30 in the morning and outside the damp walls of the Conciergerie there are the first purple and pink glimmers of the approaching dawn above the restlessly slumbering city. He notices then that the woman beside him has paused and is leaning slightly against the thin rope that leads down the spiral staircase that leads down to the cells, panting slightly and holding her side.

‘Citizeness, would you like some water?’ he asks in a low voice, cautious in case this small act of kindness should be overheard by the wrong ears and later used against him.

The woman looks at him in surprise then nods. ‘That is very kind of you, citizen,’ she murmurs, her eyes widening further as he then, after a moment of deliberation, removes his hat and offers her his arm – a gracious action of now old fashioned courtesy that she has not seen for a very long time. She looks at him more closely, noting that he is young and has a tanned, open, honest face that marks him out a provincial, not a Parisian. She wonders if he is one of the men who accompanied her husband to his death or took her young son away from her, but then concludes that they all look the same these new men of the people in their sombre blue uniforms and with their closed expressions and besides, it hardly matters any more anyway.

They carry on to her cell and she can hear the murmurs of the other prisoners as she goes past, can sense their eyes staring at her from between the bars of their cells. She has been in this prison for a few months now, the long empty days and nights sliding into each other. She had hoped that she would be allowed to mingle with the other prisoners, perhaps see a few friendly faces but instead she had been kept apart from the outset, able to hear their laughter, tears and chatter from her high, barred window that overlooked their exercise yard but unable to communicate in any way.

Rosalie, the maid who has cared for her in prison, is waiting for her in her cell and the woman sees straight away that she has already heard the news and is doing her best to fight back tears, to appear as jolly and confident as usual. In the past the woman had had dozens of maids, haughty, fashion obsessed young women with deft fingers who could expertly tie a corset, fasten a diamond necklace or curl her long fair hair. In contrast, Rosalie has short, stubby fingers, frequently knocks things over and has no idea how to dress hair properly. She is worth a hundred fashionable maids though and shows the woman a loyalty, kindness and friendship that she had not known was possible and believes to be a God given comfort in these, her final hours.

‘They have brought paper and ink, Citizeness,’ the girl says now, proudly showing them to the woman. ‘So that you can write a letter.’

The woman, who had once caused ripples of consternation and annoyance throughout Europe for both her unwillingness to put pen to paper and general inability to form a coherent sentence in any of the languages that her mother had painstakingly ordered that she have lessons in, sits down with alacrity at the rickety little table, words already tumbling around in her mind as she pulls the paper towards her.

For a few moments she deliberates over who the letter should be addressed to – her brother perhaps? One of her sisters? A few words of wisdom for her children? Or perhaps it should be to one of her brothers in law, who had been fortunate enough to escape France a few years before. No. There is only one person left on earth who had the right to hear the condemned woman’s final thoughts, to be entrusted with her last wishes and messages.

‘Ce 16 octobre, à quatre heures et demie du matin.

C’est à vous, ma soeur, que j’écris pour la dernière fois…’

The pen is cheap and scratches horribly against the paper as she writes to her sister in law, Élisabeth, who is also a prisoner in Paris, fully aware all the while that there is a very high probability that her letter will never reach its intended destination and will instead fall into hostile hands. Nonetheless, this is a chance that she is willing to take as she writes speedily, crossing hardly anything out so precise are her thoughts at that moment, so clear is her resolve about what she must say before it is too late.

When the letter is finished, some of the words obscured by the bitter tears that she could not control as they dripped onto the paper, she then takes out her battered prayer book that has been a constant comfort during her imprisonment and writes:

‘This 16th of Oct. at 4.30 in the morning

My God, have mercy on me!

My eyes have no more tears

to weep for you my poor

children; farewell, farewell!

Marie Antoinette’

This done, she sits for a moment in silence, watching the guttering flickering flame of the cheap stinking tallow candle that rests in its pewter pot on the table. It casts large shadows on the damp walls of her cell and she looks at them with exhausted disinterest, remembering a time long ago when she and her sister, Carolina had pretended they were monsters from the fairytales that their poor beleaguered governess had liked to tell them at bedtime.

‘Citizeness, you should try and get some rest,’ Rosalie whispers as the gendarme who has been posted to sit in the corner of the cell and watch the two women, stretches and yawns.

Marie Antoinette hides a smile. What is the use of rest now? She obediently gets up though and lies on her bed for a while, crying silently and thinking about those who are dear to her, her hands curled up into desperate fists that she crams into her mouth to stifle the screams that would otherwise overcome her.

The hours pass until finally, Rosalie touches her gently on the shoulder to ask if she would like to eat something. Marie Antoinette shakes her head, thinking that she would surely choke if she had to swallow something now. ‘I do not need anything,’ she murmurs so quietly that Rosalie has to lean in closer to be able to hear her. ‘All is over for me now.’

‘Citizeness, you will feel stronger if you have something to eat,’ the girl urges. ‘I can make you a bowl of bouillon, if you would care for it?’

Marie Antoinette’s stomach rumbles hungrily as she thinks of the soup and for a moment she wonders at the way that even though it is so close to death, her body still has its needs and demands. Surely it should be above hunger now, she thinks.

It does not take Rosalie long to prepare the soup and her mistress sits silently on the edge of her narrow bed, ignoring the staring gendarme and only looking up briefly to give a flickering, wan smile when the girl hastens back, bearing a white bowl filled with steaming bouillon and a plate with a few pieces of bread.

‘Please try to eat,’ she implores. ‘I know that you don’t think that it is worth it, but you want to seem strong don’t you?’ She wipes away a tear and lowers her voice. ‘We can’t have you fainting, Citizeness.’

Marie Antoinette nods, seeing the sense of the girl’s argument. She has lost a lot of blood lately from a protracted menses that began shortly after her arrival at the Conciergerie and has continued ever since. Once upon a time, a crowd of court doctors had been called to attend upon her every sneeze or headache but now as she slowly weakens and her body betrays her by adding to the daily indignities that she already suffers, there is no one to care for her.

She takes the bowl of soup onto her lap and dips the spoon into it. ‘Noodles, Rosalie?’ she asks.

The girl beams, pleased that her mistress has noticed. ‘Your favourite, Citizeness,’ she says. ‘To give you more strength.’

Marie Antoinette smiles to herself as with an effort she swallows some of the bouillon, savouring its rich, meaty flavor as she rolls it around her mouth. At Versailles, she had horrified the court chefs, used to catering for generations of greedy Bourbons with her insistence upon only eating the simplest and freshest of foods and then only in the smallest of portions. Now though she thinks back regretfully to the banquets of richly spiced meats, cakes, jellies and creamy sauces that she had determinedly ignored while pushing a few pieces of plain boiled chicken around her green and white Sèvres plate.

‘Have you thought about what you want to wear,’ Rosalie asks, this time looking nervous. Marie Antoinette notices that she is twisting her spotless, white cotton apron between her hands as she speaks. ‘It’s just that the Committee of Public Safety have sent a message saying that you are not to wear black mourning.’

She stops eating and stares up at her. ‘I am not to wear mourning?’ It had in fact been her attention to go to her doom dressed all in black, to both show proper respect for her dead husband and also to remind the populace of his fate. ‘But this is preposterous.’

‘I am sorry, Citizeness,’ Rosalie says, clearly miserable that it fell to her to deliver this edict from above. ‘You are to wear any color but black.’

Marie Antoinette, a woman who once had the command of one of the most enormous wardrobes the world has ever seen, stuffed full of dresses in all conceivable hues, in all possible fabrics and who once as a young girl refused to wear black because it made her cheeks look too pink, can’t help but smile at the irony of this moment. ‘But I have only one dress that isn’t black,’ she says.

Her clothes and toilette had once been the hot topic of conversation throughout Europe and indeed the whole world. People had jostled each other out of the way as she passed by on her way to Mass at Versailles and Fontainebleau, just to see what she was wearing on that day. She, her ladies in waiting and her favorite modiste Rose Bertin had spent hours upon hours sitting together in her delicate white and gold sitting room beneath the palace eaves, their heads close together as they plotted another amazing outfit that would bedazzle and awe all who saw her in it.

Her wedding gown alone had preoccupied the courts of both Vienna and Versailles for several months as they rowed about the precise type of lace that should edge the wide panniered skirts and the quality of diamonds that littered the stiff taffeta stomacher. How odd then that her final toilette, the dress that she was to wear on this, her last and most crucial appearance should be such a contrast.

Rosalie brings out a simple white cotton dress and places it on the bed as carefully as if it were made of gold thread and covered with starbursts of diamonds and pearls. They stand for a moment and stare at it before Marie Antoinette gives a tiny nod and slowly, with shaking fingers pulls off her cap. ‘What a pity that the committees seem to have forgotten that the Queens of France used to wear white when in mourning,’ she murmurs wryly and she and Rosalie share a secret smile.

‘Monsieur, please could you do the goodness to turn away and look at the wall?’ she asks the gendarme, who mulishly shakes his head.

‘Orders are orders, Citizeness,’ he says.

‘For the love of God, Monsieur, have you no compassion?’ she is shaking with rage and upset now, conscious all the while that her body has betrayed her once more and again blood is seeping from her, staining her white linen chemise, which will now need to be changed.

‘Citizeness, I will do my best to shield you,’ Rosalie whispers with a dirty look at the man, who shrugs unconcernedly and goes back to examining the black dirt beneath his fingernails.

Awkwardly, clumsily the young maid removes Marie Antoinette’s clothes, doing her best to hide her at the same time and finally holding up a threadbare sheet as her mistress, pink cheeked with shame, removes the stained chemise and swiftly pulls on a fresh one before fastening a black petticoat around her waist, praying that this will hide the blood from view.

It does not take them long to dress her and Rosalie stands back and gives a sad, satisfied nod before she pulls a tiny pair of scissors out of the pocket that hangs at her hip. ‘I thought you might prefer it if I was the one to cut your hair, Citizeness?’ she whispers. ‘I hear that Sanson, the executioner, can be very rough and wanted to spare you that.’

Marie Antoinette gives a tiny gasp and reaches up to touch her hair, thinning now and gray where once it had fallen in luxurious, silken strawberry blonde ringlets to her waist. ‘Oh no,’ she whispers, tears springing to her eyes. They had cut her hair once before, when she was a child and was recovering from small pox and she still remembered sobbing as she perched on a too high chair, watching her long curling locks piling up around her pink silk slippers.

‘I am sorry, Citizeness, but it must be done,’ Rosalie murmurs.

Her mistress nods then and sits down on the bed, staring straight ahead as with a sad sigh the girl sets to work shearing the former Queen’s once beautiful hair, which had been so gorgeous at one time that a shade of silk had been named after it and for an entire season all the most glamorous women in Europe had worn shoes in the shade of ‘Cheveux de la Reine’. Some long white strands fall across her hands as she holds them in her lap and she picks them up to curiously examine them before listlessly allowing them to drift to the floor.

******

Check out my new alternative lifestyle blog, Gin Blossoms!

‘Frothy, light hearted, gorgeous. The perfect summer read.’ Minette, my young adult novel of 17th century posh doom and intrigue is now £2.02 from Amazon UK and $2.99 from Amazon US.

Blood Sisters, my novel of posh doom and iniquity during the French Revolution is just a fiver (offer is UK only sorry!) right now! Just use the clicky box on my blog sidebar to order your copy!

Follow me on Instagram.