As some of you may have discerned from various mumblings on my blog’s Facebook page, I am currently frenziedly working away on a novel about Marie de Guise, the mother of Mary Queen of Scots. It’s proving to be my most challenging work yet, but I am thoroughly enjoying writing it and hope to have it finished by the end of the year. Anyway, perhaps surprisingly, someone who seems to be getting quite a lot of mentions is Marguerite d’Anjou, Queen of England, who is an object of some admiration to the young Marie de Guise and was in fact her great aunt as her father, Claude de Guise was the grandson of Marguerite’s younger sister, Yolande.

In fact, as an aside, I’m getting REALLY into Marie de Guise’s (and by extension Mary Queen of Scots’) genealogy as it is far more illustrious than I had originally expected, incorporating as it did close family relationships with several royal families as well as the Dukes of Milan (Marie de Guise’s great aunts Bona and Charlotte of Savoy married the Duke of Milan and King of France respectively), Savoy and Bourbon. There’s even those all important lines of descent from Charlemagne, St Louis and er Melusine de Lusignan (one of Marie de Guise’s great great grandmothers was a princess of Cyprus). She wasn’t even the first Queen of Scotland in her family – her great aunt, Marie de Gueldres (the aunt of her formidable grandmother Philippa de Gueldres) was Queen to James III and great grandmother of her husband James V.

Anyway, I digress from the point of this post, which is Marguerite d’Anjou, who was born on the 23rd of March 1430 in Pont-à-Mousson (another Marie de Guise connection here – she was educated at the Convent Sainte Claire in Pont-à-Mousson under the auspices of her grandmother Philippa de Gueldres), the daughter of René, Duc d’Anjou and his wife, Isabelle, who was Duchesse de Lorraine in her own right and acted as regent during the many absences of her husband while he was pursuing his claims to the thrones of Naples, Jerusalem and Sicily – an example of female power and authority that the young Marguerite evidently took very much to heart.

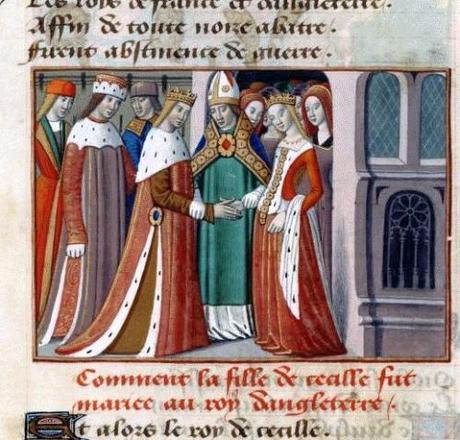

Marguerite herself was married to Henry VI of England at Titchfield Abbey on the 23rd of April 1445 at the age of just fifteen. The glorious victories of her husband’s father, Henry V, were a fading memory by this time and his conquests in France were already ebbing away and vanishing back into French control despite a rather undignified scramble to have the young Henry VI, his heir, crowned as King of France in Notre Dame. The Valois claimant to the title, Charles VII, who had, in contrast to his rival, been crowned King of France at Rheims with all the traditional pomp and under the watchful eye of Jeanne d’Arc, both of which served to strengthen his claim to the throne, was loath to marry one of his own close relatives off to the English pretender to the throne, as it was a female claim to the French throne, that of Isabelle de France, the wife of Edward II, that had started all the trouble anyway. Instead he agreed with alacrity to a proposal that Henry marry Marguerite, who was of suitably royal lineage but not so royal that it could cause potential ructions to the French royal succession. Furthermore, he took this opportunity to take back control of Maine and Anjou in lieu of paying a dowry – a move that further dented England’s already tenuous grip on France.

Poor beautiful Marguerite, so headstrong, intelligent and capable found herself the wife of a man who although he was actually eight years older, seemed much younger than herself. While her long dead father in law, Henry V would have made a superb match for this vibrant and strong willed young woman, his son was rather less well suited, being of a shy, pious and retiring nature, which eventually descended into some form of mental instability, perhaps schizophrenia or a catatonic depression. However, Marguerite, despite the fact that her own personality was very much at odds with that of her husband, did her best to be a loyal and supportive consort and whatever dissatisfaction she may have felt with her husband was very well hidden – her antipathy towards various of his nobles, in particular her husband’s cousin, the Duke of York, who was keen to promote his right to claim the throne should Henry die without an heir, was much less carefully guarded however and would have calamitous repercussions.

However, things began to take a bad turn when Henry suffered what seems to have been a complete mental breakdown and slipped into a catatonic state in the summer of 1453, a collapse that was probably brought on by the loss of Bordeaux, another large chunk of his father’s legacy. It was badly timed as far as Marguerite was concerned as she was pregnant with what would prove to be their only child – a feat which provoked all manner of gossip as to how she had managed to conceive a child with the pious, simple minded Henry, from which it wasn’t much of a leap to suggest that the baby must have been fathered by someone else. The gossip took a sinister turn when the baby, born on the 13th of October 1453 and named Edward, turned out to be a male heir. If Marguerite and Henry’s child had turned out to be a daughter then the gossips would have twittered away and the nobility would have quietly resolved that the girl would never come within sniffing distance of the throne, however a boy born amidst such rumor and speculation was an altogether different matter.

Emboldened by the examples of her own female relatives, Marguerite made an attempt to be named regent during her husband’s now prolonged incapacity but this proposal was blocked by the supporters of his cousin, the Duke of York, who was furthermore a rival claimant to the throne. Certainly, interested parties at this point would have been weighing up the benefits of having an incapacitated king as opposed to an entirely new one who had the gumption and military prowess to perhaps claw back some of the losses in France.

However, to Marguerite’s relief, Henry made a soap opera worthy SURPRISE! recovery on Christmas Day 1454, over a year after he had had his breakdown, which had been so severe that he had remained completely unaware of his son’s birth during that time. Not that Henry’s clear bewilderment at being presented a lively toddler and being told that this was his son and heir did anything to put a stop to the ever increasing rumours put about the supporters of the Duke of York, whose short lived regency was now at an end but who had clearly enjoyed his first taste of proper power, that the child was not in fact his.

The Marriage of King Henry VI to Margaret of Anjou, Grignion, mid 18th century. Photo: National Portrait Gallery, London.

It took only a few short months after Henry’s recovery for things to reach a head when both sides completely fell out after the king, probably egged on by Marguerite, reversed much of the work that York had done during his regency to promote his own supremacy, thus alienating York and his powerful supporters. Mix in Marguerite’s outrage when it was suggested that York be given the consolation prize of being proclaimed heir instead of her son Edward; an ongoing territorial dispute between the great Northern lords and the exclusion of York and his supporters from the Great Council called by Marguerite and conflict seems inevitable. The first military clash occurred at St Albans in May 1455 and resulted in a defeat for the royal army and, worse still, the capture of Henry by the triumphant Duke of York. However, the unfortunate king’s life was in no real danger at this point – even his enemies conceded that a weak witted king made for a much better opponent than the fearsome Marguerite and her son, both of whom had slipped the net.

The following years were gruelling for Marguerite as, separated from her husband who remained under the control of the Duke of York, she struggled for what she saw as her son’s birthright – realising that due to her husband’s mental state and generally malleable nature, whoever was in charge of his person, was effectively in charge of the entire realm and that as this was currently the Yorkist faction headed up by the Duke, his brother in law, the Earl of Salisbury and his nephew, the Earl of Warwick, she might as well kiss goodbye to her son’s inheritance unless she managed to summon up some pretty hardcore supporters of her own and turn the situation around. This parlous situation only intensified when York’s right to the throne after Henry VI was officially recognised in October 1460 and he was declared Prince of Wales, effectively usurping her son’s own title and position.

Things took a surprise turn for the better though just a couple of months later in December 1460, five years after the defeat at St Albans when her chief commander, the Duke of Somerset managed to defeat the combined armies of the Dukes of York and Salisbury at the Battle of Wakefield, leaving both York and Salisbury dead along with York’s eldest son, the Earl of Rutland. However, if Marguerite thought that her problems were over with the deaths of the Dukes of York and Salisbury, she was to be quickly disabused when York’s second son, the charismatic Edward, Earl of March stepped up to the plate and took on not just his title but also his war, alongside his cousin, the Earl of Warwick, ambitious son of the Earl of Salisbury, both men being pretty keen to avenge the deaths of their respective fathers and brothers at Wakefield.

However, it all kicked off with a disaster for Warwick when he was soundly defeated by Marguerite’s forces at the second battle of St Albans in February 1461 – a defeat made all the more resounding when the Queen was able to recapture back her King, who was discovered obediently sitting beneath a tree close to the battleground, guarded by a handful of Yorkists, his duty as unwilling figurehead for the legitimacy of the Yorkist control over the country done and dusted for the day.

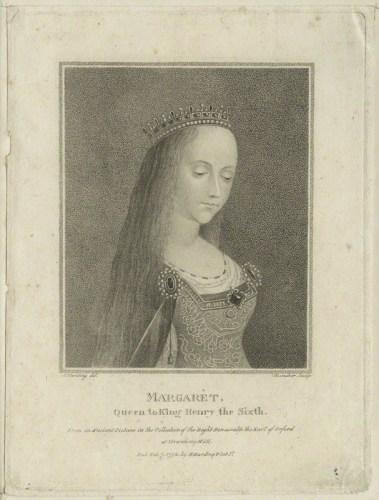

Queen Margaret of Anjou, Schenecker, 1792. Photo: National Portrait Gallery, London.

With Henry back under her control, Marguerite ought to have been unstoppable but her side was to suffer a reversal of fortune when the gates of London remained barred to her triumphant forces (her troops had been less than well behaved during the journey south and rumours of their savagery had preceded her with the result that the always suspicious Londoners didn’t want to risk letting them lose in their city), which forced her to retreat away back to the north and also buoyed up the Yorkist morale, which had been at a pretty low ebb after the defeats at Wakefield and St Albans, encouraging Warwick and the new Duke of York to throw their all into one last ditch attempt to overthrow Marguerite and Henry and march on to London themselves, where the gates were thrown open and York was declared Edward IV. Marguerite was predictably extremely unhappy about this and it all came to a head just over a month later with the Battle of Towton, that byword for military brutality, a blood bath that ended with what was considered to be a definitive victory for the house of York under the aegis of Edward of York, who now pronounced Henry deposed and himself the absolute and definite King of England. Marguerite, Henry and their son promptly headed off to the relative safety of Scotland there to lick their wounds and plan their comeback tour.

It all seemed pretty hopeless at this point though – the new king, Edward was extraordinarily popular, particularly with the Londoners and few people seemed keen to have Marguerite and Henry with all their problems back again. A feeling that seemed underlined when Henry, who had been living as a fugitive in the north of England, was eventually captured by Edward in 1465 and held in a state of luxurious captivity in the Tower of London, where he seemed, to be fair, pretty content to remain while no one seemed particularly eager to reinstate him on the throne. Yes, a mentally feeble puppet king had his uses but a strong, handsome young king with actual intelligence and military ability was clearly even better.

Meanwhile, Marguerite and their son, Edward, had made their way to her native France where they lived in a rather less than luxurious exile supported by her father, the Duc d’Anjou. Although Marguerite never stopped scheming and agitating for a glorious return to power in England, her pleas for assistance from the French King, by now the wily Louis XI, fell on deaf ears however and it seemed like she would have to resign herself to her fate – a lifetime of impotently bolstering up her son’s claim to the throne, followed by the inevitable retirement to a convent.

However, while Marguerite was champing her teeth at her enforced exile to France, things were taking a distinct turn for the worse over the channel in England when those apparently inseparable cousins in arms, Edward IV and the Earl of Warwick started to gradually fall out and were at increasing odds with each other – the decline in their relationship being spurred on by Edward’s marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, which caused considerable embarrassment to Warwick, who was negotiating a match with France at the time and now looked like he was overstating his influence over the young king. The inevitable big falling out occurred in 1469, when Warwick married his own eldest daughter to Edward’s younger brother George, Duke of Clarence, in direct defiance of the King’s own express refusal to allow the match, which would give Clarence enormous wealth and vast tracts of lands in the event of Warwick’s death. Hostilities ensued, which resulted with Edward being taken captive by Warwick, which meant that England now had TWO imprisoned Kings – which even Warwick could see was an untenable situation so he decided to let Edward, who was understandably completely enraged, go.

Marguerite had of course been watching all of this with great interest and resumed her attempts to extract some promise of help from Louis XI, who now began to see some advantage to meddling a little in affairs across the Channel. Warwick and his family had hastened to France in the wake of Edward’s restoration to liberty and Louis saw this as a golden opportunity to get Marguerite off his back, although one can imagine his trepidation when he first suggested to both she and Warwick, who were pretty much mortal enemies, that they might like to patch up their dispute and join forces against their common foe: Edward. Amazingly this unlikely stratagem worked and was even reinforced by the marriage of Warwick’s younger daughter Anne to Marguerite’s son, Edward, which, if their plans were successful, was an amazing coup for the ambitious Warwick although it probably didn’t go down quite so well with Anne’s rapacious brother in law, George of Clarence.

Plans for an invasion went ahead with Warwick and Clarence landing back in England with their forces in the Autumn of 1470. At first it was a great success and they had Henry restored to the throne by October of that year, while Edward IV quickly went off into exile to his sister’s court in Burgundy and his wife, Elizabeth hurried off to sanctuary at Westminster Abbey with their daughters. It didn’t take long to unravel again though – whereas Edward IV’s brother in law, the Duke of Burgundy had been sympathetic to his plight, he had been unwilling to commit very much in the way of actual money and man power to the Yorkist cause, despite the urgings of his wife that he should help her family out a bit. However, his great enemy Louis XI had demanded, in exchange for his own support with the invasion of England, that Warwick promise that he would lend English support to any wars that he might wage against Burgundy.

Possibly Warwick had thought that he wouldn’t have to make good on this promise for quite some time to come, but unfortunately a declaration of war swiftly followed his restoration of Henry VI and Warwick was forced to unwillingly back the French with the might of England, with the result that the Duke of Burgundy’s vague interest in the squabbles of his in laws took on a more serious bent and he in turn lavished enough money and troops on Edward to enable him to take back his throne.

What a disaster for Marguerite. She had remained somewhat circumspect and had refused to so much as set foot in England until her son’s safety was guaranteed. Unfortunately, her arrival back in the country, with her son in tow, coincided with Edward IV’s triumphant return and after the defeat and death of Warwick in the battle of Barnet in April 1471 and the reconciliation of Clarence with his elder brother, who was rather more forgiving than most would have been under the circumstances, Marguerite found herself trapped and forced to engage with Edward IV’s troops at Tewkesbury a few weeks later on the 4th of May.

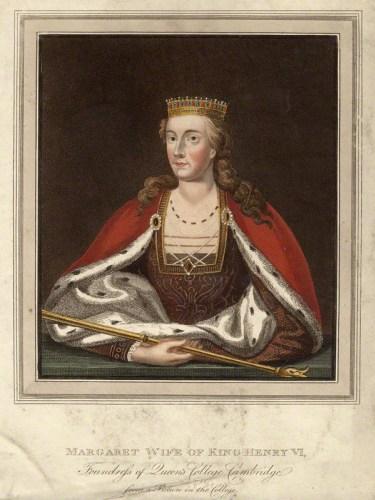

Called Queen Margaret of Anjou after Unknown artist, probably late 18th century. Photo: National Portrait Gallery, London.

It all ended in complete disaster, with the absolute defeat of Marguerite’s remaining forces and, much worse still, the death, either in battle or at the hands of his brother in law George of Clarence, of her only precious son, who was just seventeen years old, which left her predictably devastated. She had kept the young Edward close to her throughout their long years of exile in Scotland and France, had adored him, fostered his claim to the throne and even refused to risk his presence in England until Warwick was absolutely able to guarantee his safety – not realising that time had already run out for all of them thanks to the simultaneous rivalry between France and Burgundy. Her son’s death was a terrible blow to Marguerite – after all she had pretty much devoted her life to the battle to claim his birthright for well over a decade. What did she have to live for now?

Marguerite was taken prisoner after the battle and seems to have raised little resistance, probably sensing that the war, for her at least, was almost certainly over and possibly also feeling that the world now held very little interest for her now that Edward was gone and there was nothing left to fight for. When Edward returned triumphantly to his capital, she formed part of his victory parade – crushed and miserable and staring straight ahead in her carriage, her demeanour no doubt echoing that of Marie Antoinette being drawn through the streets of Paris in her tumbril in October 1793: proud, defiant and yet still utterly broken.

Like Marie Antoinette, Marguerite was also a widow by this point – her husband Henry having died in his rooms in the Tower of London towards the end of May, just a few weeks after the destruction of the Lancastrian forces at Tewkesbury. WHAT A COINCIDENCE. The official story was that he had died of grief but it seems likely that he was murdered by order of Edward IV, who had nothing to fear from the death of his rival now that Henry’s son was dead and his wife captured and rendered completely impotent.

Marguerite’s imprisonment lasted for four years – first at Wallingford Castle and then the Tower of London, where she was placed in the care of her friend, the Duchess of Suffolk and accorded some luxuries in recognition of her former rank. Eventually she was ransomed by Louis XI and returned to the care of her family, eventually dying on the 25th of August 1482 at the age of fifty two, a relic of darker times.

Although she seems like a difficult person to like and had a life that seemed to veer from one calamity to the next, I have a real admiration for Marguerite d’Anjou. It can’t have been easy for her with her intelligence and strong will to be married off to a man whose abilities were in no way comparable to her own and yet she seems to have really wholeheartedly thrown her lot in with him, both ferociously trying to see off any attempted usurpations of his authority and then later devoting her life to protecting and fighting for the birthright of their son. Marguerite d’Anjou, this lover of badass women and lost causes salutes you.

******

Set against the infamous Jack the Ripper murders of autumn 1888 and based on the author’s own family history, From Whitechapel is a dark and sumptuous tale of bittersweet love, friendship, loss and redemption and is available NOW from Amazon UK and Amazon US.

‘Frothy, light hearted, gorgeous. The perfect summer read.’ Minette, my young adult novel of 17th century posh doom and intrigue is now 99p from Amazon UK and 99c from Amazon US. CHEAP AS CHIPS as we like to say in dear old Blighty.

Blood Sisters, my novel of posh doom and iniquity during the French Revolution is just a fiver (offer is UK only sorry!) right now! Just use the clicky box on my blog sidebar to order your copy!

Follow me on Instagram.