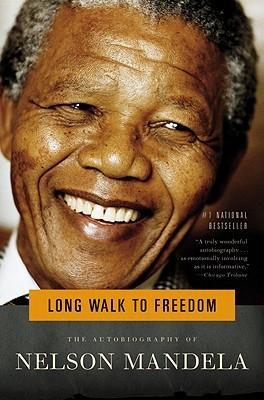

Book: Long Walk to Freedom by Nelson Mandela

Genre: Autobiography

Publisher: Little, Brown, & Company

Publication date: 1994

Pages: 638

Source: Library

Our book club selection for December proved to be a great focus for discussion at this time.

Summary: Long Walk to Freedom covers Nelson Mandela’s life from birth to inauguration, covering the development of Apartheid, the decades-long struggle against it, and the demolishing of it, symbolized by the election of Mandela as President of South Africa.

Thoughts: Our diversity book club discussed Long Walk to Freedom in December, a little more than a week after the Grand Jury announcement that Officer Wilson would not be charged in the shooting death of 18-year-old Michael Brown. Our book club meets in the same county where Brown died, the same county that convened the Grand Jury. These events directly impact us and our neighbors.

As it turned out, Nelson Mandela’s autobiography was the perfect fit for the night. We were able to say many things that needed to be said, while continually coming back to the book, to Mandela’s life and words. We found a lot relevant and a lot to be hopeful about.

Here were some of the passages that struck me.

On managing mass gatherings and the officers policing them:

The crowd began yelling and booing, and I saw that matters could turn extremely ugly if the crowd did not control itself. I jumped to the podium and started singing a well-known protest song, and as soon as I pronounced the first few words the crowd joined in. I feared that the police might have opened fire if the crowd had become too unruly. p. 156

On reasons for establishment opposition to integration:

This is precisely why the National Party was violently opposed to all forms of integration. Only a white electorate indoctrinated with the idea of the black threat, ignorant of African ideas and policies, could support the monstrous racist philosophy of the National Party. Familiarity, in this case would not breed contempt, but understanding, and even, eventually harmony. p. 249

On the ubiquitous of the apartheid mind-set, even in Mandela’s thoughts:

We put down briefly in Khartoum, where we changed to an Ethiopian Airways flight to Addis. Here I experienced a rather strange sensation. As I was boarding the plane I saw that the pilot was black. I had never seen a black pilot before, and the instant I did I had to quell my panic. How could a black man fly an airplane? But a moment later I caught myself: I had fallen into the apartheid mind-set, thinking Africans were inferior and that flying was a white man’s job. I sat back in my seat, and chided myself for such thoughts. p. 292

In my year of reading books about England, I got a kick out of Mandela’s confession to being an Anglophile, especially admiring the British parliament and the sense of what it means to be a gentleman. “While I abhorred the notion of British imperialism, I never rejected the trappings of British style and manners.” p. 302

A speech in court about the law, conscience, and protest:

The law as it is applied, the law as it has been developed over a long period of history, and especially, the law as it is written and designed by the Nationalist government is a law which, in our views, is immoral, unjust, and intolerable. Our consciences dictate that we must protest against it, that we must oppose it and that we must attempt to alter it….Men, I think are not capable of doing nothing, of saying nothing, of not reacting to injustice, of not protesting against oppression, of not striving for the good society and the good life in the ways they see it. pp. 330-331

How an oppressive system negatively impacts both the oppressor and the oppressed — and the hope that both get better when the system improves:

Badenhorst had perhaps been the most callous and barbaric commanding officer we had on Robben Island. But that day in the office, he had revealed that there was another side to his nature, a side that had been obscured but that still existed. It was a useful reminder that all men, even the most seemingly cold-blooded, have a core of decency, and that if their heart is touched, they are capable of changing. Ultimately, Badenhorst was not evil; his inhumanity had been foisted upon him by an inhuman system. He behaved like a brute because he was rewarded for brutish behavior. p. 462

On respecting the experiences of the young. When those arrested during the Soweto Uprising began to show up in the same prison as Mandela, they regarded him as a moderate:

After so many years of being branded a radical revolutionary, to be perceived as a moderate was a novel and not altogether pleasant feeling. I knew that I could react in one of two ways: I could scold them for their impertinence or I could listen to what they were saying. I chose the latter. pp. 484-485

Appeal: This is a very readable, though long, autobiography. It took me about a month to read it and I looked forward, each day, to my journey to South Africa in Mandela’s footsteps.

Challenges: This is my 22nd book for the Nonfiction Reading Challenge in 2014. I’m pretty sure that’s more nonfiction than I’ve read in a single year since I read my way through the 92s in my middle school library.

Challenges: This is my 22nd book for the Nonfiction Reading Challenge in 2014. I’m pretty sure that’s more nonfiction than I’ve read in a single year since I read my way through the 92s in my middle school library.

Have you read this book? What did you think?