Lady Ann Fanshawe's Icy Cream on a 1660s blue dash charger - the original family brick

In the late seventies, I placed a successful bid on a mixed lot of books in an auction. There were five volumes in the lot, including the two eighteenth century cookery books I was actually hoping to buy. At first I thought the other three were of no interest to me. However, I started skimming through one of them and after a few pages realised that it was a fascinating read. I had accidentally bought a book that was to become far more important to me than the two fairly pedestrian Georgian recipe collections in the same box. It was Sir Nicholas Harrison Nicolas's edition of Lady Fanshawe's Memoirs (London: 1829). I had never heard of Ann Fanshawe (1625-80). Nor at the time did I realise that as well as her memoirs, she had written a collection of recipes, which I now believe to be one of the most important of the Stuart period.

Lady Ann's Memoirs first found their way into print in 1829 in this volume edited by N. H. Nicolas

I got so hooked on the life and adventures of this remarkable woman that a few years later I spent a day examining the original 1676 manuscript of her memoirs in the British Library (Add. 41161). However, it was many years later before I realised the Wellcome Institute Library had another Fanshawe manuscript in its collection - Lady Ann's handwritten book of medical and cookery receipts (Wellcome MS. 7113). Ever since I bought the Nicolas edition of her memoirs. this remarkable lady has haunted my life in some extraordinary ways. Let me explain. In a later illustrated edition of her memoirs (1905) edited by Beatrice Marshall, the art historian Allan Fea mentions two paintings - one of Ann and another of her husband Richard, both after Sir Peter Lely. Fea describes them as belonging to a Captain Stirling. Although I had seen the well known portrait below by Cornelius Johnson, on which the engraved frontispiece above by Meyer is based I could not track these other portraits down.

Cornelius Johnson. Portrait of Lady Ann Fanshawe. c. 1660.

Then last year, I was giving a talk about seventeenth century cookery books in the library at Ardgowan House near Inverkip in Scotland and happened to glance up at the wall. I could not believe it. Lely's portrait of Ann was staring down at me! A conversation with Ardgowan's owner Cindy Shaw Stewart, revealed that the painting was on loan from Pollok House, which had once been in the ownership of Sir William Stirling! The portrait after Lely of her husband Richard is at Ardgowan too. Problem solved, and in such an ironic way too - at an event called The Art of Dining! An hour before spotting the portrait I had actually described Lady Ann's recipe for ice cream in my lecture as the earliest one in Europe! Talk about synchronicity! In the Ardgowan 'Lely', Ann is considerably older than in Johnson's celebrated portrait above. She is wearing a diamond jewel at her breast. Interestingly she describes such a jewel in her memoirs as having been given to her in 1665 by Queen Elisabeth, wife of King Philip IV of Spain, when Ann's husband Richard was Charles II's ambassador to the Spanish court.

Lady Anne in later life - after Lely. I copied this from Beatrice Marshall's 1905 edition of the Memoirs. The painting, together with another of Sir Richard Fanshawe, is at Ardgowan House, Inverkip.

She may have also learnt about iced refreshments at the Madrid court. In her memoirs she describes watching King Phillip and Queen Elisabeth at table in 1665,

'The King and Queen eat together twice a week in public with their children, the rest privately, and asunder. They eat often, with flesh to their breakfast, which is generally, to persons of quality, a partridge and bacon, or capon, or some such thing, ever roasted, much chocolate, and sweetmeats, and new-laid eggs, drinking water either cold with snow, or lemonade, or some such thing.'

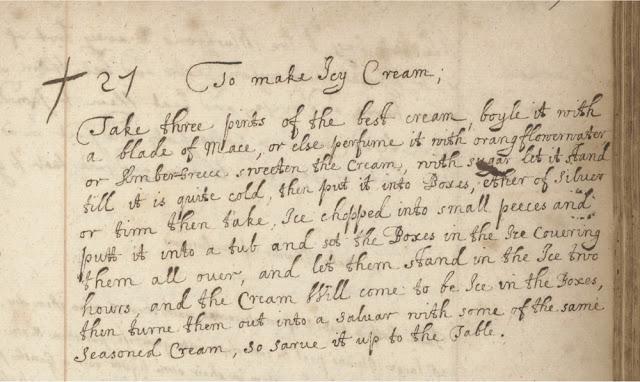

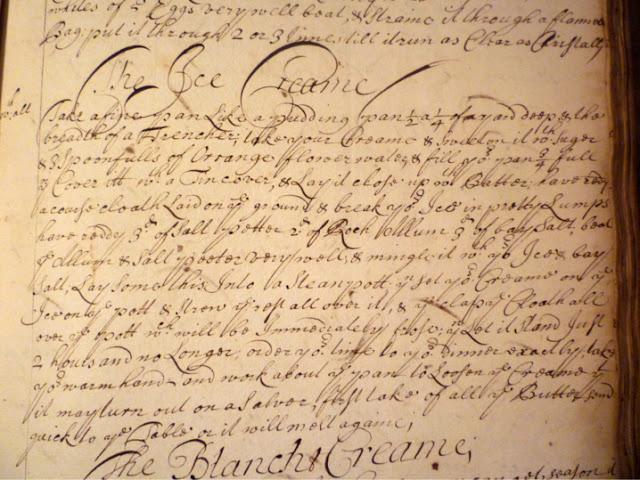

The earliest known recipe for ice cream in a section of Ann's receipt book dating from the mid 1660s. © Wellcome Collection.

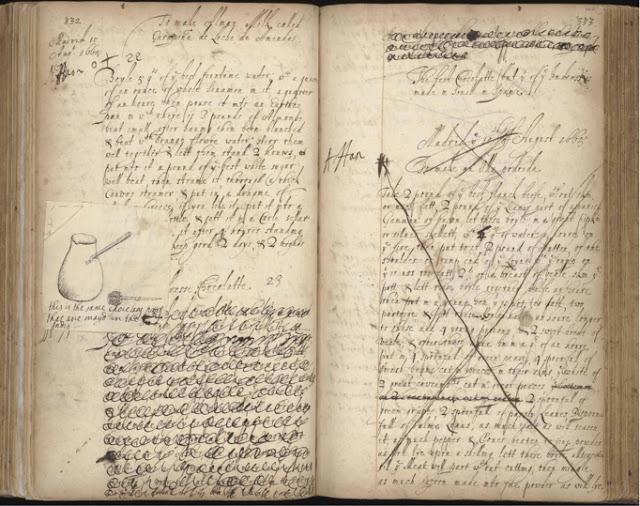

Chocolate is mentioned a lot in her memoirs of Spanish court life. In her receipt book, she gives some instructions for preparing it. She also gives us a drawing, which I suspect is the earliest English depiction of a chocolate pot and mill.

© Wellcome Collection.

The House of the Seven Chimneys in Madrid. Lady Ann's home when her husband was ambassador to the king of Spain

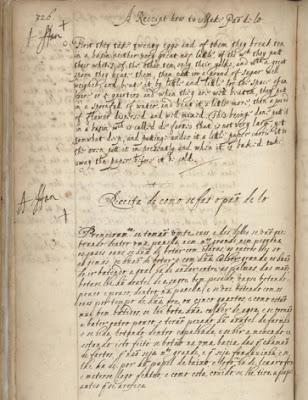

Ann also spent some time at the court in Lisbon. Her husband Richard was sent there by Charles II in 1662 to negotiate for the hand of Catherine of Braganza. A recipe in Portuguese for paõ di lo, the celebrated sponge cake still made in Portugal must date from this time. As far as know, this predates the first recipe printed in Portuguese in the second part of Domingos Rodrigues' Arte de Cozinha. (Lisboa: 1680), which contains a recipe for Paõ de ló amendoas. Anne was very much an international woman and her recipe collection reflects that she was interested in the food of the countries she visited as an ambassador's wife.

Paõ de ló. © Wellcome Collection.

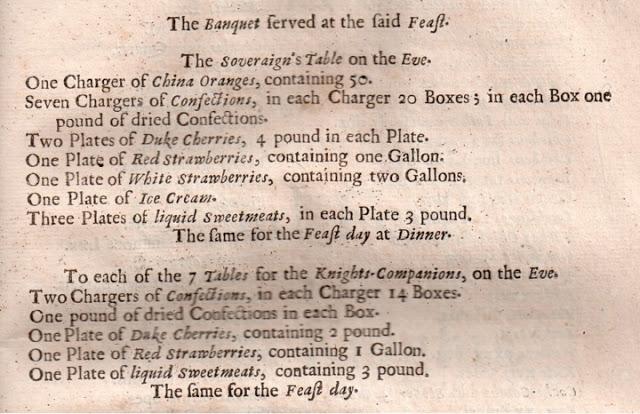

As to her Icy Cream, unfortunately her recipe does not work, because she or her clerk (the recipe is not in her hand) forgot to include a crucial ingredient - the salt or saltpetre which acted as the refrigerant when added to ice or snow. But I think this is an oversight, because everything else rings true about the recipe. Ann tells us that her husband served Charles II at his first garter feast at St George's Hall, Windsor in 1661. There is no surviving menu from that occasion, but the bill of fare of another garter feast ten years later in 1671 was fully documented by Elias Ashmole, who tells us that one plate of ice cream was served during the banquet course, but only on the sovereign's table. We will never know what the king's ice cream was really like on this occasion, but I suspect it was made along the same lines as Ann's Icy Cream.

The bill of fare for Charles II's banquet course at the 1671 Garter feast from Elias Ashmole, The Institution, Laws & Ceremonies of the Most Noble Order of the Garter. (London: 1672).

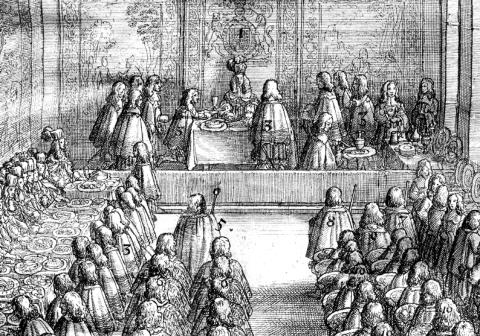

Charles II eating the second course of this Garter feast. A detail of an etched illustration by Wenceslaus Hollar in Ashmole's book.

In 1977, about the time that I first read the Fanshawe memoirs, I found a recipe for ice cream in a manuscript among a small collection of books in the Herb Society, where I often lectured. I realised that this book was written in the 1690s by Grace, Viscountess Carteret, later known as Countess Granville (1654-1744). At the time I was unaware of Ann Fanshawe's 1660s recipe, so thought that Grace's was the earliest English recipe for ice cream. Viscountess Carteret gives more detailed instructions and tells us to mix the refrigerant chemicals roch alum, bay salt and saltpetre with the ice. So her recipe, unlike Ann's does freeze very well. In fact I tried it out and served it to some friends in London at the time. They all liked its creamy texture and orange flower flavour, an unusual treat in seventies London!

Grace Granville, Lady Carteret's Ice Cream recipe c. 1690.

John Smith (after Johann Kerseboom).

Grace, Viscountess Carteret and Countess Granville.

Mezzotint

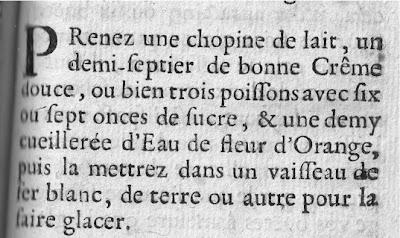

Audiger's 1692 Crême glacée

Take a chopine (pint) of milk, a half septier (8 oz) of good sweet cream, or else three poissons (12 oz – more usually spelt posson) with six or seven ounces of sugar and half a spoonful of orange flower water, then put it in a vessel of tin, earthenware or other (material) to freeze it.

Both Lady Fanshawe's and Lady Carteret's ice creams were frozen in a metal box embedded in ice and salt

I made Lady Ann's Icy Cream at a recent presentation I gave at Clarke Hall in Wakefield, though I used Lady Carteret's modus operandi to ensure it froze properly. I served it on a 1660s blue dash charger decorated with a motif of Prince Charles's vessel returning him back to England for his restoration to the throne. At the time both Richard and Anne Fanshawe were on board with the prince, so I thought this was an appropriate plate upon which to serve her icy cream. I flavoured it with mace, orange flower water and ambergris as per her instructions. Although it was frozen in a brick shape, it was not hard and grainy, as the many people who tried it at Clarke Hall will testify. In fact it was delicious and very creamy.

To give you some idea of what initially drew me to this remarkable woman, here is a brief, but tragic description in her own words of the various fates of her lost children. She gave birth (or miscarried) twenty times. Despite this almost unbearable burden and the additional death of her beloved husband Richard in Madrid in 1666, through out her memoir Ann never complains about her lot.

“My dear husband had six sons and eight daughters, born and christened, and I miscarried of six more, three at several times, and once of three sons when I was about half gone my time. Harrison, my eldest son, and Henry, my second son; Richard, my third; Henry, my fourth; and Richard, my fifth, are all dead; my second lies buried in the Protestant Church-yard in Paris, by the father of the Earl of Bristol; my eldest daughter Anne lies buried in the Parish Church of Tankersley, in Yorkshire, where she died; Elizabeth

The ruins of Tankersley Hall near Barnsley in Yorkshire, where Richard and Anne lived for two years.

lies in the Chapel of the French Hospital at Madrid, where she died of a fever at ten days old; my next daughter of her name lies buried in the Parish of Foot's Cray, in Kent, near Frog-Pool, my brother Warwick's house, where she died; and my daughter Mary lies in my father's vault in Hertford, with my first son Henry; my eldest lies buried in the Parish Church of St. John's College in Oxford, where he was born; my second Henry lies in Bengy Church, in Hertfordshire; and my second Richard in the Esperanza in Lisbon in Portugal, he being born ten weeks before my time when I was in that Court.”If you would like to read Lady Anne Fanshawe's memoirs, they can be downloaded from the internet.

A digital version of her manuscript receipt book can be read on the Wellcome Library website.

Clarke Hall Website.

Come to our Art of Dining course (June 9-11th 2012) at beautiful Ardgowan House and see the Lely portraits of Lady Ann and Sir Richard Fanshawe.