Just across the road from Harrods, a sign advertises a delicacy you won't find in its food halls: Montpelier Mineral Water. The sign seems to be almost the only trace of this company; but they did really exist, and several of their bottles survive.

Image: Toolmaker1 on Bottledigging UK

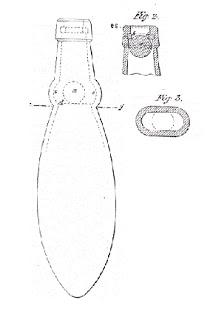

These are Codd bottles, encapsulating another piece of London history. Victorian engineer Hiram Codd worked for the British & Foreign Cork Company; seeing the shortcomings of corks for carbonated drinks, he invented a new way of sealing bottles. His globe-stoppered bottle had a rubber washer and marble; the pressure of the drink held the marble against the washer, sealing it. To open the bottle, the marble was pushed inside; the bottle neck was shaped to stop it blocking the bottle again.

To market his product, Codd drew upon the network of mineral water companies in the capital. London may seem a surprising source of mineral water (an Only Fools and Horses episode comes to mind). However, the appalling quality of Thames water - and the more rural nature of many areas now wholly urban - made local mineral waters viable products. Their appeal also came from being carbonated, using methods invented in the late eighteenth century. Thus Codd could experiment at a small works on the Caledonian Road, and take as partner the father of Camberwell's Malvern Mineral Water Co.

The new product was a great success. Almost as soon as the bottle launched in 1873, Codd had issued 20 licences to mineral water soda companies; he had a further 50 applications. Factories in Kennington and Camberwell produced the glass marbles - a curse to later bottle collectors, because children would smash the glass to get at the marble.

In 1885, Codd died; he is buried in Brompton Cemetery, close to this works which used his product. If Knightsbridge seems an unlikely place for a works of any kind (Bonhams auctioneers are across the road from the former Works), that was less true in the late nineteenth century. The Montpelier Estate, of which this street formed the eastern boundary, was neighboured by working-class dwellings; the street was noticeably less grand than the square it led into, and had a variety of shops. Even when the area moved more uniformly up-market after the First World War, the Estate's residents had to fight off Harrods' proposal to build a large bakery on Montpelier Street. Today, though, the sign serves as an incongruous reminder of a more industrial past.